The Disallowed - Part 2 of 2

You get ejected! And YOU get ejected! And YOU GET EJECTED! Not you, though, Regan, you stay right where you are.

We’re very pleased to present the conclusion to “The Disallowed.” Here’s the first part, if you need to stop over there.

Where we last left off, it’s August, 1968, and umpire Chris Pelekoudas had created a special, customized purgatory for the Chicago Cubs’ best relief pitcher, Phil Regan, who he suspects of throwing a grease ball. Two Cubs have already been ejected, but Regan is not one of them, and he is about to try, after 30 minutes of chaos and arguing, to get the Reds’ leadoff hitter out for the second time in the same at-bat.

Given a second life, the Reds leadoff pinch-hitter, Mack Jones, grounded out, and this time Pelekoudas let him sit down. The next batter doubled, but from there Regan finished the inning successfully and without further objections. The ballpark took an uneasy breath.

The Reds’ starter, George Culver, worked a scoreless seventh and then Regan returned for the top of the eighth. No one in the Cubs’ dugout was going to remove him, not if the umpire’s wouldn’t. This time he faced the minimum with the help of a double-play ball and Pelekoudas allowed it all. If not for the absence of Leo Durocher and Al Spangler, what happened in the top of the seventh might have been a dream.

The bottom of the eighth inning began with the Cubs still trailing the Reds 2-1 and Regan, who would be out to finish the game in the ninth, had a chance to scavenge yet another win if the Cubs could make a late comeback. First, though, he’d have to bat for himself, just behind his batterymate, Randy Hundley.

Hundley led off with a single. Regan came to the plate with the intent to bunt and sacrifice himself, moving Hundley to first. He hit the ball a little too hard, though, allowing the Reds to force Hundley out at second. As far as the potential outcomes went, this one was only arguably worse than grounding into a double-play, as Regan would now have to linger on base before going back to the mound. He called for his warm-up jacket to wear out on the bases, as pitchers stuck in this situation often did, back when pitchers on the bases was a thing.

The next Cub batter, Don Kessinger, grounded out, and Regan advanced to second on the play.

Then, second baseman Glenn Beckert slapped a single to right field. And here is where things get, from a modern perspective, rather fantastical.

On Beckert’s hit, Regan took off running, so determined to score and tie the game that he ran straight through a “stop” signal from the third base coach, Pete Reiser.

This set up a play at the plate. In the outfield, Pete Rose scooped up the ball and fired it home, where the Reds’ catcher, Pat Corrales, set up in front of the plate to catch the incoming throw.

Coming toward home, Regan realized the throw would beat him, so he did something that would make Pete Rose proud. Phil Regan, the Cubs’ most important relief pitcher by far, threw himself into a bone-crushing takeout slide in hopes of making the catcher drop the ball.

Regan plowed into Corrales, who went flying, but when he rolled over, the catcher opened his mitt to reveal the ball still inside. Regan was out.

“That play,” Dave Bristol, the Reds’ manager said, “was worth the price of admission alone.”

Pitcher George Culver, three outs away from a complete game, would bat for himself to lead off the Reds’ ninth inning. As he came to the plate to begin his at-bat, Culver noticed a few objects lying in the dirt, very near where Regan and Corrales had collided. He picked them up and examined them.

According to Culver, he found two or three “slippery elm” lozenges, used to generate spit, and a half-used tube of Vaseline. Remember that Regan had put on his jacket out on the bases, perhaps forgetting what had been secreted in his pockets. At least, that was Culver’s theory.

Culver turned to Pelekoudas and the Cubs’ catcher, Hundley, neither of whom had apparently noticed this unusual debris. This was Culver’s account:

I looked at the umpire. He looked at me. I also showed them to Randy Hundley. Nobody said anything, so I put the stuff behind me, took my cuts, and struck out. Then I picked it up and gave it to [manager] Dave Bristol.

I thought I was showing it to the umpire, but he wasn’t looking, I guess. I never did say the stuff belonged to Regan but I had some suspicions.

Chris Pelekoudas, meanwhile, denied that any of this happened. He denied Culver had showed him anything before that ninth inning at-bat, even though such evidence, produced in that moment, would have largely proved him right about Regan’s illegal pitches.

“If he did find it near home plate, he should have given the evidence to me,” Pelekoudas said.

Hundley certainly wasn’t offering any insight into the interaction, and Regan scoffed at the reported findings. “I can go buy a tube of Vaseline, take it out to the mound, and say I found it there and it belonged to Culver.” Circumstantial evidence it was, but what circumstances they were!

So, we have a Reds pitcher planting evidence or lying about finding evidence; or actually finding evidence, and/or(!) we have an umpire failing to notice or perhaps ignoring the very evidence (legitimate or otherwise) that proved his own case. We tried to use Occam’s Razor on this situation and it broke.

We can’t really linger on this episode of CSI: Wrigley, because the next batter up was Pete Rose, and Phil Regan had apparently decided that despite being under the closest scrutiny he’d ever experienced as a pitcher, it was the perfect time to settle a lingering score.

This game, we swear.

All through the game, Rose had the usual target on his back in in right field, made larger than usual by the altercation with Regan a week before. He was booed any time the crowd had occasion to look at him and folks in right seemed to lose hold of their trash with unusual frequency.

Regan had not forgotten their dust-up, either. He’d just missed Rose in the lineup when he entered the game in the seventh, but Pete’s turn had come again. Regan’s first pitch went straight over Rose’s head, forcing him to drop into the dirt.

The next pitch was way inside, brushing Rose back. Neither pitch resulted in admonishment from Pelekoudas, as both were “legal” fastballs. Where Regan aimed them was not his business.

The message sent, Regan got to work and threw a few strikes. With a 2-2 count, Rose got (what he remembered as) a spitball. “I swung at that s.o.b. as hard as I could and missed.”

Except, he didn’t!

Chris Pelekoudas thought it was a spitball/grease ball, too. He called another illegal pitch and “disallowed” another out. On his way back to the bench, Rose remembered the umpire bark, “Come on back, Pete, that’s a ball.”

Seeing Rose return to try again, Wrigley Field seethed. At this point, John Holland, the Cubs’ vice president and general manager, actually called the National League offices in Cincinnati to warn that a crazy umpire was going to get them somebody killed.

“I called because it was getting very difficult to handle the crowd,” Holland said. “They were trying to get onto the field. After Pelekoudas warned Regan, he should have followed the rule and thrown him out of the game. Instead, he kept giving them extra outs. This incensed the crowd which was getting difficult to handle.”

The Cubs certainly could not take this development lying down, but authority figures to throw out were in short supply, so catcher Randy Hundley offered his services, unkindly remarking on Pelekoudas’ striking and aquiline nose and becoming the day’s third ejection.

Rose dug in again and singled to right field. “Hell, anybody can get a hit with four strikes,” Rose said to Doug Harvey, the first base umpire.

Bedlam was only averted because Pete Rose and Dave Bristol were manic button-pushers. Bristol came out to see Rose at first base and told him to steal second on the first pitch.

The Cubs’ backup Randy, Randy Bobb, was now behind home plate, and he and Regan saw Rose leaning. They executed a perfect pitch-out, allowing Bobb to make a strong throw to nail Rose at second base. John Kibler was the umpire there, he called Rose out. Rose threw his batting helmet into the air, earning the day’s fourth and last ejection and sending the crowd’s mood into a sharp U-turn.

To recap:

Doug Harvey ejected Leo Durocher (arguing)

Shag Crawford ejected Al Spangler (bench-jockeying)

George Pelekoudas ejected Randy Hundley (abuse)

John Kibler ejected Pete Rose (grandstanding)

And no one ejected Phil Regan (alleged repeated cheating)

We’re didn’t do the full research on this point, but if this wasn’t the only time in history when each member of a four-man umpiring crew ejected a different individual, it must be on a pretty darn short list of such games.1

The crowd cheered wildly as Rose departed the field, and Rose, thinking his day was done and that he’d be safely on the team bus an hour later, answered the fans with what one account referred to as “the Italian salute.”

“I forgot there was a second game,” he admitted later. “They gave me hell in that second game.”

“I could have had a feast out there,” Rose said. “There was enough chicken—one breast looked pretty good, too.”

So, again to recap, we have:

A rare instance of spitball discipline and the first time, according to the Chicago Tribune, that a player had received discipline for throwing a spitball without being caught going to their mouth for spit.

An umpire making up a new type of in-game discipline: “suffering”

A bang-bang play at the plate and a takeout slide by a star reliever

Possible evidence planting by the Reds

And Pete Rose almost getting hit by a chicken (cooked, this time2)

Regan finished the inning, the Reds won 2-1, and we’re going to go lie down for a minute.

In between the games, Rose listened from the locker room as thousands of fans chanted “We want Rose, we want Rose!”

A reporter found the Reds’ right fielder magnanimous in victory. “You don’t think that incident last Saturday had anything to do with it?” he asked the writer, grinning. “It’s all right. It’s the way the game’s played. That’s why [Regan’s] a good pitcher.”

Nearby, one of the Reds, Tony Cloninger, canceled plans to travel up to the press box for an interview, as the press box in those days was only reachable via a route through the public grandstands. “I’m not going up there, as wild as those fans are.”

He was wise to stay away from the Cubs’ locker room, too, safely on the other side of the park, where Leo Durocher virtually shouted his postgame comments at a crowd of delighted reporters.

They’ll not get away with this!

Pelekoudas is definitely ruining Regan’s livelihood as a pitcher and on that basis I will seek court action besides laying the problem before the commissioner. If the ball was a spitter, as contended, then the rule clearly provides that the pitcher must be taken out after being warned. Why wasn’t Regan taken out after he was warned three or four times?

I don’t think they know what the hell they were doing. I asked Mr. Pelekoudas if he was so sure my man was making illegal pitches, why didn’t he do what the rules say and eject him?

But what I really want to know is what brought all this on. That’s the answer I want from the commissioner’s office or the league office.

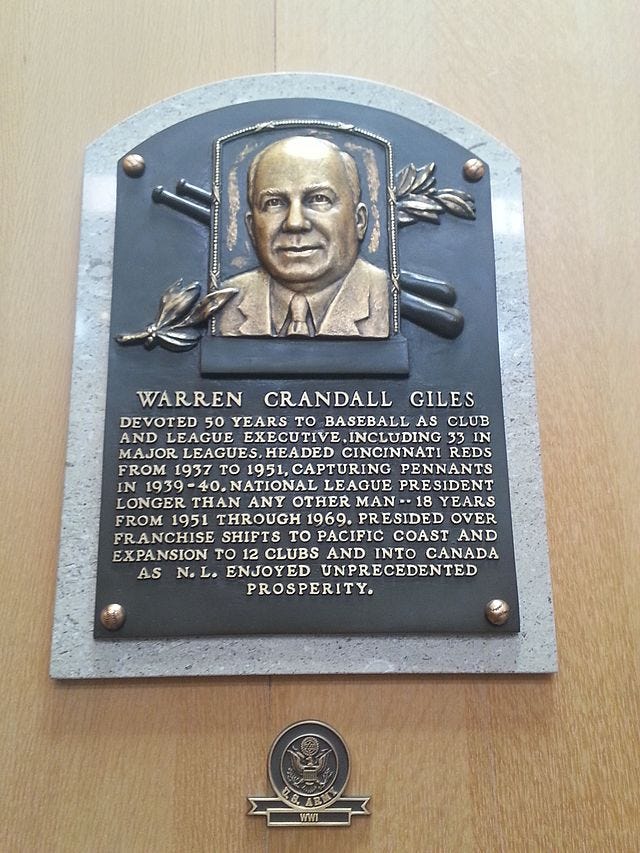

General Manager Holland had already called for a meeting with Warren Giles, the National League president.

“They ridiculed our man,” Holland said. “They were invited to take Regan to the clubhouse and examine him. But no. They accuse a man of cheating but have no evidence.”

Speaking of proof, the Reds’ Dave Bristol, human evidence locker, had strangely little to say. “I think Pelekoudas showed a lot of guts in making the calls and all I wanted to do was win the game. I was only out on the field for explanations.”

“I’m not saying anything until I’ve talked to some people,” said Regan, who seemed embarrassed and defiant.

Pelekoudas is lying when he said he found Vaseline on my cap. What he felt was sweat and nothing else. I for one would like to know how Pelekoudas or anyone else can detect a spitter. I don’t think they’re that smart. How are they going to determine a spitter from the break of the ball? In my opinion, they can’t do it.

The umpires’ dressing room was a popular between-game destination, never a good thing for the men trying to hide out there after dispensing some Old-Testament-style justice.

“It’s a crime,” Shag Crawford said, “when you have to go out and search a pitcher. It’s a disgrace to the game and the players.”

“But what the hell can we do?” Pelekoudas chimed in.

They gripe about low batting averages and illegal pitches. Now there are complaints when we call it. Let’s hope more umpires start calling it. He was out there defying us. So all we did was our job.

I warned Regan on the first pitch to Jones that he was throwing an illegal type of ball. Regan complained to me that he was not doing anything wrong with the ball and when I told him he was, he told me I was endangering his livelihood and threatened to take me to court.

If they want to go to court, just give me the time and date. I’ll be there with my attorney and God as my judge and witness!

We cannot think of a baseball game more deserving of subsequent litigation than this one. Here’s hoping…

There’s a funny thing about doubleheaders and ejections. It had not always been so, but by 1968, the rule said people were ejected from the game, not the day, meaning just an hour later, Rose, Durocher, and Hundley were back in their usual positions. Hundley was known for catching both ends of a doubleheader and August 18 would be no exception. Even Al Spangler, not even a restorative night’s sleep between him and his earlier bloodlust, was back and got a pinch-hit at-bat.

Pelekoudas rotated over to third base and Regan would not see action in the afterpiece, though he would be missed.

Rose, showered in Italian salutes and much more, rapped out four straight hits, including a home run. His teammate and future consigliere Tommy Helms pointed out that trying to scare Rose only served to antagonize him, and he hit better when he was mad. Afterward, Rose admitted the frothing bleacher crowds motivated him. “I usually try to put out 115 percent, today I tried 125 percent.” Over the whole series he hit 11 for 20, if you count that single after his “disallowed” out (and the official scorer did).

In any case, it was enough—the Reds swept the day and the series and had won six straight. The Cubs had done the exact opposite.

The events of August 18, 1968 came back frequently to Rose, including how it ended, which he recounted nearly ten years later, in 1977:

I’ve had a pretty good series, and I’m pretty happy as I leave the clubhouse, a gift bottle of champagne under one arm and my carry-on bag in the other. Three cops are outside the door, I know ‘em all, so I say, ‘See you guys.’ They tell me ‘We’re escorting you to the bus.’ That’s when I see about a thousand people at the bottom of the stairs waiting for me and chanting, ‘Big ugly bear! Big ugly bear!’

A girl sneaked up and tried to hit me with one of those miniature bats and a cop decked her. Those fans ended up rocking the bus and breaking the windows. If we had had to come back the next day, they’d have had to have the militia out.

This was not a case of the tale growing tall after a decade. Just days after the games, in a regular column he wrote for the Cincinnati Enquirer, Tommy Helms verified the bones of Rose’s account, including the police escort. “Cub fans,” he observed, “take their baseball seriously.”

Especially when the umpire did not.

Two days later, the Cubs’ brass got their meeting with Warren Giles, the NL President, who came to Chicago to sit down with Regan, Durocher, and Holland. Pelekoudas was not invited, which was a good sign for the Cubs.

Giles was a year away from retirement after nearly two decades as the chief official for the Senior Circuit, and he had no desire whatsoever to spend his final years in baseball trying to chase the spitball out of modern-day pitching. His reduced aspirations were reflected in the statement he released the next day.

“I know Phil Regan and I have respect for him and I felt a gentleman like he should be shown the consideration and courtesy of hearing him,” Giles wrote. “Phil told me he didn’t have Vaseline or other lubricant on his sweat band and I believe him.”

He continued:

Chris Pelekoudas suspected he did have lubricant of some kind, but told me his judgment of the illegal pitch was based almost entirely on the action of the ball in flight, and [he] seems convinced it acted like a so-called ‘spit-ball.’

This is a most difficult problem for the umpire and they are being urged on all sides to enforce violations of illegal pitches.

Giles said that for the time being he’d ask the officials to focus on finding proof on a ball before calling a violation.

Being in town, Giles stayed for the day’s game at Wrigley. Leo Durocher pinned his statement up in his office and showed it off to reporters like a college acceptance letter. Regan worked two scoreless innings and the umpire crew (a different one) held their peace.

Two days closer to retirement.

In a collective protest of Giles’ perceived betrayal, not a single umpire, including Pelekoudas, enforced the substance prohibition in 1969. There were, on the other hand, three ejections that year for people who excessively complained about doctored pitches, and two of the three so tossed were Dave Bristol and Pete Rose, in separate incidents.

It would take the arrival of a new NL administration in 1970, led by Chub Feeney, to convince officials they’d now have proper support in cracking down on spitters and grease balls, so long as they did it by the book.

Back on his beat, Pelekoudas caught Gaylord Perry with a greasy forearm in the very first series of 1970. After making him towel off, Pelekoudas promised an ejection if he saw a questionable pitch thereafter. After that, Perry realized he needed a new pitch if he wanted to remain employed and began working on a forkball.

Seven years remained in Pelekoudas’ umpiring career, but in that time he only made five ejections, none for doctored baseballs, capping off a total of 24 across his entire 15 years on the job, an extremely modest total. He participated in several National League Championship Series, including the first one in 1969, and a real spicy one in 1973, but never again would he be the center of attention as he was on August 18, 1968. He seems to be a Project 3.18 one-hit wonder, but what a hit it was.

Thanks to Warren Giles’ high regard for his character and Dave Bristol’s mysterious decision to sit on the evidence, Phil Regan kept his livelihood and (perhaps) his place on the unwritten list of 15 spitball artists for a few more years. His best seasons were behind him after 1968, but he was still pitching in 1970, when he told the Miami Herald that ever since that battle with Pelekoudas, he’d been a marked man, subject to almost daily inspections of his hands, glove, cap, ball, and a variety of other spots depending on how a given umpire imagined he would try to do it, if he were the pitcher.

Regan was pretty fed up, saying he felt “harassed” by the umpires over the last three years. “It’s time to stop this nonsense. I’m not going to stand for anybody putting their hands on me again.”

Well, the reporter asked, can you say definitively that you do not throw a spitter? To clear this up?

“My own wife doesn’t even know,” Regan said. “I’m sure not going to tell you.”

Got to keep that edge.

This is another one of those games nobody talks about anymore, but with your help, we hope to right this wrong. It won’t be easy, but the world must know what happened here. Go, and spread the word.

Now, we need a palate-cleanser after all this pettiness and shadiness. What could be better, then, than a tale of baseball standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the rest of the nation in an existential fight between good and evil. And yes, there will also be a forfeit, because it’s time for…

“The Story of the Scrap Metal Children” - coming on April 29!

The official baseball-reference.com ejection records and several contemporary accounts actually credit the Durocher ejection to Pelekoudas, which actually makes more sense. However, having found at least one source that supports the narrative we want, we’re going with Harvey to complete the set.

That’s right, guess who was in right field at Dodger Stadium on September 4, 1971, when someone released a live rooster onto the outfield grass?

You make my Mondays. Thanks.

We had the seat on the bricks behind home plate right by the Andy Frain usher who had a seat on the field. It was unbelievable what when on in that first game. Pelekoudas would come to get new balls from the usher and when the bedlam broke out my mom who was part Greek and knew a few cuss words let him loose on him. Everything he was hearing in English he ignored but the not the Greek. He came over pointed to mom and right in front of us told the usher that if he heard another cuss from her she would be thrown out of the park!