The Doctor - Part 1 of 2

Friskings, video surveillance, chemical analysis. For baseball’s preeminent spitball maestro, it was just a typical week.

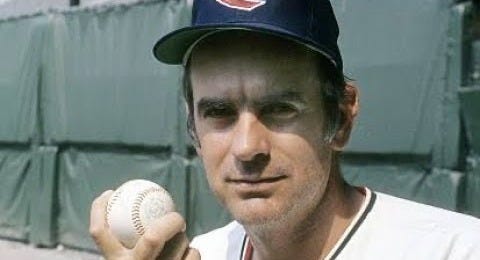

By 1973, everyone knew that Gaylord Perry cheated.

“Of course he does,” one former teammate said. “He uses Vaseline or something like it. Before that he used saliva.”

After nine years in San Francisco and two in Cleveland, the pitcher’s repertoire was well-known. “Perry alters the baseball with glop,” one writer explained. “From saliva to slippery elm to Vaseline to a lubricant known as K-Y1 lubricating jelly.”

But where did he keep the stuff he applied to the ball? “Here, there, and everywhere,” a teammate from San Francisco said. “It’s all over.”

Another former Giant, Hal Lanier claimed Perry altered his glove to create a small hole into an open chamber which he’d fill with various greases and ointments. “He would grind the ball there to get a dab,” Lanier explained. “He doesn’t need much.”

“It’s in several places,” another teammate said. “Behind his right ear and under the top of his uniform shirt at the neck.” In the early 1970s, Perry’s team, the Cleveland Indians, wore pullover-style jerseys, cream white or cherry red. “The pullovers have V-necks, and he cuts a little hole at the bottom of the ‘V’ and puts it in there.”

Umpire Dave Phillips recalled that visiting Perry out on the pitcher’s mound “was like walking into your son’s or daughter’s room when they had a cold and they had Vicks VapoRub all over their chest. Your eyes always got kind of watery when you got near him because he had so much Vicks on him.”

One of his former catchers refused to divulge any methodology, citing the Italian honor code of omertà, but did offer that Perry’s uniform had to be washed separately from the rest of the team’s laundry.

In 1973, the New York Yankees’ center fielder was a talented slugger named Bobby Murcer, who had stepped capably into real estate previously occupied by the likes of Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle. That summer, Murcer got his own Gaylord Story.

It began in Cleveland on June 25. The Yankees had faced Perry twice already and by now they knew what to expect. Out on the mound, he twitched incessantly, moving his hands around his body like a pianist over the ivories, rubbing his brow, the sides of the underbill of his cap, his jersey, his pants. And when he finally threw the ball, it behaved…unnaturally.

Murcer got off to a good start against Perry, singling into left in the top of the second inning. In the fourth inning, he grounded out to second base. In the sixth inning, he grounded out again.

The Yankees were losing, 4-1, in the eighth inning when Bobby Murcer came up once more. He swung at and missed a hard-diving pitch, but then jumped out of the box as if stung. He began loudly complaining to the home plate umpire, Lou DiMuro. Perry had thrown an illegal pitch.

“The one I swung at, I knew [Perry] had so much [stuff] on it, that I figured we might find it,” Murcer said. “I could complain every time I go to the plate, but I thought I could jack things up in the eighth. We needed something.”

Umpire Dave Phillips described Perry’s greaseball as “a ball that rolls across a table (at 88 mph) and then gets to the edge and falls straight down.” The pitch was easy to identify, once you’d been on the wrong end of a few. Murcer had now been on the wrong end of one too many. The Yankees’ manager, Ralph Houk, stormed out of his dugout. Houk practically force-marched DiMuro out to the mound, demanding Perry be inspected.

“He had ‘it’ on his wrist,” Houk said. As he and DiMuro walked to the plate, Perry turned and seemed to wipe something.

“I saw him wipe it off,” Houk said. “He has it so many places but this time it was on his wrist. And I couldn’t get DiMuro out there fast enough. Perry was grinning when we got there. He knew we weren’t going to find it.”

Houk tried anyway. He told DiMuro to check Perry’s wrists–nothing there. Houk wanted the cap checked, and as Perry removed it, the manager snatched it away to examine it himself. The sight of the pitcher’s bald pate delighted the hometown crowd of 18,670, as it was a sure sign that their ace had Houk and the Yankees right where he wanted them. Houk even put his nose to the inner band of Perry’s cap. “Smell it!” he told DiMuro, shoving it at the umpire.

This was not Perry’s first cranial exam, and he had a can’t-miss line ready. “Sure it stinks,” he said afterward. “They only give me one cap a year. It’s bound to smell by now.”

“All I smelled was sweat,” DiMuro said. “I looked at the ball, his pants, his cap, and I couldn’t find anything.”

Few umpires in the league were prepared to match wits with Gaylord Perry, who saw a body search as just another step in the tango. Umpire Ron Luciano described the Perry’s tendency to start giggling as soon as umpires began touching him, trying to make the process as uncomfortable (and cursory) as possible—“Who wants to touch Gaylord Perry’s sweaty body?” Other times Perry feigned anxiety as umpires began to search a part of his body, leading them to think they were close, only to find the target area completely dry.

Foiled, Houk slouched back to the Yankees’ dugout and Bobby Murcer continued his at-bat. The Yankees were not done, however. In a show of tradecraft Perry would have admired, Murcer decided that he would bunt the next pitch foul, right into the hands of the Yankees’ coach, Dick Howser. If that ball had been “doctored,” Howser could show DiMuro the proof before any of the Cleveland defenders could erase it.

Murcer made a great effort, poking the ball down the third-base line, but the ball stayed closer to fair than was ideal. As a result, the Cleveland third baseman, John Lowenstein, and Howser both charged for the ball. Howser got there first.

“I saw a spot on it,” Howser said. “It was a smear, but DiMuro said it was only mud.” For his evidence collection efforts, Howser received the night’s only ejection.

“I threw him out for trying to show me up,” DiMuro said. “He was trying to make a circus out of it. I am trying to run a ball game and I can’t be passing out balls to everyone who wants to look at one.”

“All but two pitches [Perry] threw were spitters,” the Yankees’ shortstop, Gene Michael, said. “That’s the most I’ve ever seen him throw.”

One of Perry’s catchers later explained that Perry started each game using three legal pitches. If one or more of those proved ineffective, “he’d start in with the shenanigans.” Perhaps June 25 had been a particularly off-night.

Murcer concluded his at-bat with another single, but a fly ball ended the inning. The Yankees got a run in the ninth inning when catcher Thurman Munson hit a solo home run, but that was it; they lost, 4-2. Munson had a simple explanation for his success against Perry: “I hit the dry side.”

As we wrote in a previous story, spitballs were an everyday feature of baseball up until 1920, when Cleveland’s third baseman, Ray Chapman, was struck in the head and killed by an errant pitch thrown by Carl Mays, a noted spitball pitcher. Mays had not intended to throw at Chapman, and the tragedy highlighted the fact that spitballs could be very difficult to control. Dave Phillips again:

When people hear about a guy throwing a spitball, they might think he can do it just by putting a little spit on his hand or grease on his finger. It is not nearly that simple. A lot of veteran pitchers, I think, try to learn how to throw it later in their careers if they think it will help them stay in the big leagues for a few extra years. What they learn, however, is that it is not an easy pitch to throw. Perry had really mastered the pitch and learned how to throw it.

As a rookie in the early 1960s, Perry had failed to break out in his first two attempts in San Francisco, and he realized his career had come to an early crossroads. Determined to establish himself as a big-leaguer, he fell in with a teammate, Bob Shaw, who both taught him the spitball pitch and helped Perry rationalize using it. “Hitters are taking bread out of your mouth,” Shaw warned his young pupil. Was Perry going to let them? Long after the student had eclipsed the master, Shaw’s kill-or-be-killed philosophy remained with Perry. He was hungry, and he was going to eat.

Perry spent 1964 and 1965 learning to throw the spitter and did well enough to hang on with the Giants and stick in their rotation. It helped that he was six-foot-four and had a good fastball, curveball, and slider, and excellent control. He’d just been missing a little something, and now he had that, too. In 1966 he went 21-8 with a 2.99 ERA and made the All-Star team.

Perry was by no means alone in illicitly “loading up” his pitches. There were rumors about so many pitchers that the 1960s might well have featured more spitballers than the 1910s had. In 1973, the entire California Angels’ pitching corps2 was connected to the illicit craft. “Hell,” a rival American League pitcher muttered, “if K-Y went off the market, that whole staff would be out of baseball.”

In 1968, this growing crowd of practitioners—with Perry as their circumspect standard-bearer—inspired a new rule, 8.02:

The pitcher shall not apply a foreign substance of any kind to the ball; expectorate on the ball, either hand, or glove; deliver what is called the “shine” ball, the “spit” ball, “mud” ball or “emery” ball.

Forced to get creative, Perry tried baby oil, soap, fishing line oil, hairspray, and mustache wax. Vaseline worked extremely well but was long-lasting and easy to detect. The turning point came when he discovered K-Y, which was water-based and dried both clear and remarkably quickly.

Whatever was on the ball, if anything was, Perry publicly labeled the resulting pitch “a hard slider,” “a super sinker,” or, later, “a forkball.” With other pitchers, these were off-speed pitches, but (somehow), Perry threw them hard. “If he throws a forkball,” one writer observed, “it’s the fastest one ever.”

In fact, he did throw a forkball. He decided to actually learn the pitch around 1970 to add another layer to the hitter’s dilemma: Was that the forkball Perry just threw him? Or the “forkball?”

The hardest part was learning how to hide his lubricants on his person and apply them to the baseball in plain sight. “I spent hours in front of the mirror at home just practicing decoy moves,” he said, ticks that would allow him to hide his crimes in a blizzard of false positives. “Hand to the hat, hair, ear, neck, wrist, to some part of my uniform.” Footage of this routine was not easy to find, but here’s a short sample from his days with the Giants, circa 1965-67 (when it was still legal to stick your hand in your mouth).

Perry’s epiphany came when he realized that batters would do most of the heavy-lifting for him, as long as he gave them a reason. His decoy performance led batters to distract themselves worrying about his illegal pitch and trying to catch him, no matter what he eventually threw. Hitting requires total concentration and Perry could take that away from the hitter just by swiping at his cap.

After the June 25 game, Perry used every trick in his bag to answer reporters’ questions about his methods and the Yankees’ accusations, leisurely replying in his butter-smooth Carolina drawl:

The Charming Rogue:

The thing I want to know is, what’d they wait so long for? I mean, I haven’t had this much fun since last season. When they came out to check me, I finally felt at home.

The Folksy Dissembler:

I don’t think anyone my whole career got that mad, or seemed to be that mad, at me, but it was just our way of providing a little extra entertainment for a Monday night.

In keeping with that theme, Perry passed his hat around among the reporters in the Indians’ clubhouse, offering free smells. One writer observed that the bill was very damp underneath. “Perspiration,” Perry said, smiling. He wiped two fingers across his forehead and repeated it: “Perspiration. I can throw a heckuva sinker with this.”

The Self-Deprecator:

You didn’t hear them say anything when Munson hit it out.

The Evangelizer:

They’ve got a designated hitter now. Why not give us another pitch? Everything is done for the hitter and nothing for the pitcher.

Any time the other team made a fuss, it gave Perry a chance to advocate on behalf of the illegal pitches he claimed to never throw, and he took these opportunities with winking gusto. Having begun his career in the 1960s and lived through both the Year of the Pitcher in 1968 and baseball’s subsequent efforts to make his job harder, Perry saw the spitball as a proportional response.

“I’ve got a living to make,” he said. “I’m doing everything I can to win and I’m sure they are, too.” He smiled again. The smile pulled the whole act (or acts) together. It was cool, wry, and knowing, with lots of eye-contact, shading his words in a dozen directions. Was he confessing? Was he pulling your leg? Or—in what he said to you—pulling someone else’s?

In just the two since Perry arrived in the American League, Ralph Houk had seen far too much of that knowing smile. Houk knew that the more managers like him called for searches, the more power they gave Perry over their hitters. Besides, no American League pitcher had been disciplined for a spitball since 1944, so protesting was futile anyway. After the game Houk tried to extricate himself from Perry’s trap as gracefully as he could.

“I just thought the game was getting a little dull,” the manager said, puffing mildly on a cigar. “I thought I’d have a little fun. How can you tell from the dugout whether anything’s on the ball? There’s no reason to make an issue of it. You’ll never hear me knock Gaylord Perry. I wish I had four of him.”

Despite ending the night 2-for-4 against Perry, Murcer had not cooled down. He liked bread, too. While Perry did his charm-offensive across the stadium, the Yankees’ center fielder held his own impromptu gaggle with the press. “He threw it more than I’ve ever seen him throw it,“ Murcer said. “You can’t take your normal swing against that thing. It would be okay if he was overpowering, but it’s simply because he mastered an illegal pitch. Gaylord Perry cannot get by without that pitch. If they ever ban him from doing it, he’ll be gone from baseball.”

Murcer chafed at Perry’s success because he felt the sport’s leadership was enabling him. He was far from alone in holding this opinion. One insider observed that “the baseball hierarchy views throwing the spitter and sex the same way. Doing it openly is considered indelicate and if a man does it he is not supposed to talk about it, but the authorities have never made it unpopular.”

“They’re so [blank] scared they can’t do anything,” Bobby Murcer said of the umpires.

And the president of the league and the commissioner don’t have the guts to stop it.

That was a spicy quote, and Murcer knew it. “You can print that. I want them to see it. I think it’s getting out of hand when a guy just stands out there throwing spitters. I make my living playing baseball. If a guy cheats to get me out, that’s not right.”

This was usually the part where the two sides agreed to disagree and went their separate ways on the circuit. The Yankees could banish Gaylord Perry from their minds, and Perry could climb into the heads of the next squad he’d face, five days later. It might be a month or even a year before the Yankees drew Perry again.

Except in 1973, the schedule gods had decided to have a little fun of their own. After just two games apart, the Yankees and Indians would reunite, and Perry’s very next start would be the first game of that series. The rematch would happen at Yankee Stadium in New York, where the lights were even brighter and the searching eyes far more motivated. Still chafing over Perry’s antics, the Yankees hatched a plan to expose him to the world.

On November 25: “In Flagrante Delicto”

K-Y was not a household item in 1973, so its mention required a bit of delicate explanation: “[K-Y] is widely used in gynecology and surgery, among other things.”

One of the Angels’ pitchers in 1973 was Aurelio Monteagudo, 29, an up-and-down spot-starter who was regularly accused and frisked. Monteagudo was a Cuban refugee, and he wove his biography into his spitball act, explaining that the suspect pitch was merely a “Cuban palm ball.”

I find it comforting that this kind of malarkey can still grip a player or manager's psyche. To wit, the Joe Musgrove shiny ears incident.

Nice piece, Paul - Perry was the spitball king.