The Doctor - Part 2 of 2

In 1973, baseball did all it could to catch Gaylord Perry throwing illegal pitches. When they failed, he wrote a book and confessed.

In our last piece we introduced spitball master Gaylord Perry and zoomed in on the week in 1973 when he tied the New York Yankees in mental and physical knots. He might have escaped retribution, but a quirk of the schedule brought his Indians to the Yankees’ home turf just four days later, in time for his very next start. Who says revenge is best served cold?

Here’s Part 1, by the way.

In 1973, the president of the New York Yankees was Gabe Paul. Before joining the Yankees, Paul had spent twelve years as the general manager of the Cleveland Indians. In fact, it was Gabe Paul who oversaw the 1971 trade that first brought Gaylord Perry to Cleveland. In 1972, Paul stridently defended Perry from the “persecution” of the rest of the American League, going so far as to contact the president of the American League, Joe Cronin, to complain that the umpires were harassing his new pitcher with endless complaints of ball-doctoring. Sour grapes from losing teams, he insisted.

This backstory put Gabe Paul in a bit of an awkward spot on June 26, 1973, after Perry defeated the Yankees, 4-2. That morning, Paul again called Joe Cronin to discuss Gaylord Perry.

“We have to keep the game clean,” Paul said, without any evident irony. Reminded of his previous efforts to keep the game dirty, at least Paul didn’t deny it. “It all depends on where you sit. If our guys say Perry is throwing spitters, I am going to believe them.”

In fairness to Paul, he had to tow the party line if he wanted to keep his job, because he worked for George Steinbrenner, a brash young owner with no time or patience for moral relativism.

“We’re backing Bobby Murcer all the way,” Steinbrenner said. “Perry is scheduled to pitch Friday night. If he does1, we may ask to look at his glove. And we may do it frequently, because it can be on him one inning and not the next.”

Glove checks were just the beginning. The Yankees would also set up two closed-circuit video cameras and train them on the pitcher’s mound.

“The special television camera only follow Perry,” said Bob Fishel, the Yankees’ director of public relations. “It will provide slow motion, stop-action capability. There will be two trained operators to provide voice-over if they think they spot Perry doing anything unusual.” The Yankees would “make their findings available” to Cronin and the league office—if he cared.

Some said the surveillance scheme was Paul’s idea; Paul said it was Steinbrenner’s. Those two really did deserve each other.

The timing of the New York rematch offered other opportunities. Cronin kept the AL offices in Boston, but commissioner Bowie Kuhn worked out of New York, and he “invited” the Yankees’ Bobby Murcer (who had publicly questioned the intestinal fortitude of baseball’s leaders) to pay a visit to his 51st Street offices.

“I’ve been called in for Friday,” Murcer said. “I want to get this thing out in the open for the ballplayers. I’ve never caused any trouble. Maybe, together, we can find where Perry hides it.”

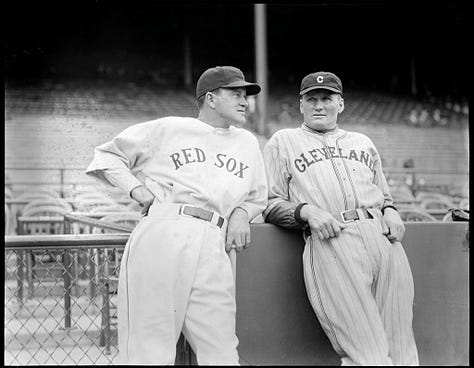

Joe Cronin was an unassuming, affable man, working in a particularly thankless job. Though he didn’t flash his credentials around, they were some of the most impressive in the business. Twenty years as a player, a lifetime batting average of .301, seven All-Star games, winner of a proto-MVP award in 1930. Fifteen years as a manager (13 while also playing), with an overall winning record and two pennants. Eleven years as a general manager (here’s about where he was voted into the Hall of Fame).

And then he became the president of the American League, in 1959, in an era when that was a real job with real responsibilities (these days it is both ceremonial and currently vacant). 1973 was Cronin’s fourteenth year as AL president, and here was some long-haired punk from the Yankees, calling him a coward. Say it ain’t so, Joe!

The man had been in baseball so long that when he first hit in the big leagues in the late 1920s, some of his opponents were legal spitball pitchers, grandfathered in under the 1921 rule change. Critics suggested if it were up to Cronin, the pitch would be made legal once again, but in the wake of Murcer’s “gutless” comments, Cronin insisted he was trying to get Gaylord Perry, on charges that the pitcher couldn’t…slip out of.

Our umpires have been told, from the time Perry came into our league, because of his reputation, to keep a close watch on him to see what he does. We’ve undressed Perry all year. They’ve searched him and wiped him off and taken the ball away from him and we haven’t found anything yet.

Cronin’s assistant, Bob Holbrook, said the investigation was ongoing. “We’re doing plenty,” Holbrook said. “We have highly skilled investigators on it, and I don’t mean cops. I mean technical men.”

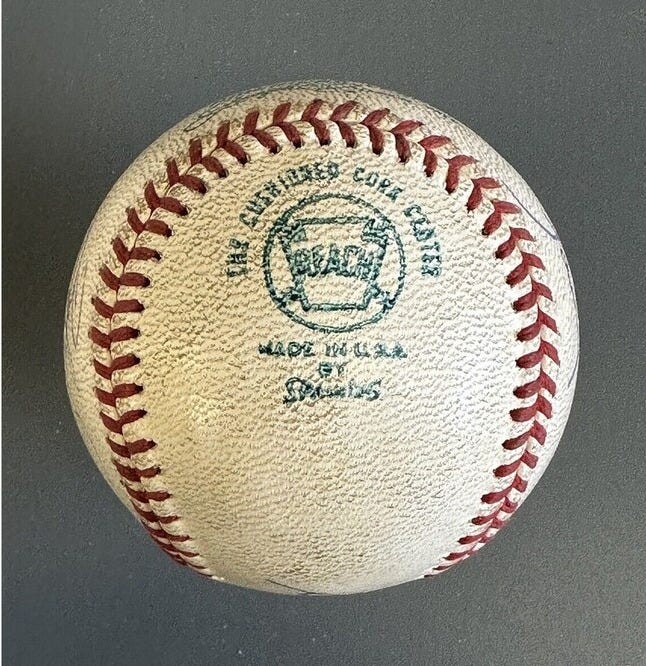

If the umpires saw a Perry pitch they suspected was illegal, they pocketed the baseball, even if it passed a sensory inspection. The flagged balls were sent to a commercial laboratory where they were scraped and tested for chemical irregularities.

If the tests had revealed anything, “Cronin declined to provide any details.” In other words, Perry had passed. They never hooked him up to a polygraph, but we’re sure he would have aced that, too.

On June 29, the day of the rematch, the Yankees announced they had dropped their plan to videotape Gaylord Perry’s movements that night, supposedly because Joe Cronin had agreed to send an umpire supervisor to discreetly monitor Perry’s start from the stands.

In clearly unrelated news, the Murcer/Perry squabble had produced such attention that ABC wanted to feature the game on their flagship television program, Wide World of Sports. The network’s star broadcaster, Howard Cosell, was dispatched to do interviews for the segment, and the Yankees had kindly agreed to let ABC film inside the ballpark.

Over in Manhattan, Bobby Murcer and the commissioner had their little chat. Eager to set the narrative, Kuhn put out a statement before Murcer even made it out to his car:

I met this afternoon with Bobby Murcer regarding his recent statements about President Cronin and myself. He apologized for his remarks. In light of the apology, I have limited the fine to $250.

At Yankee Stadium, Murcer denied he’d apologized. “I told him that we had just lost a tough ballgame and that a lot of things are said in the locker room that maybe shouldn’t be said. He told me that I should be a little more discreet in my statements.”

$250 poorer, Murcer continued to indiscreetly make his case. He’d gotten ahold of some K-Y and waved two lubed-up digits around the clubhouse.

“Look at my fingers,” he said as the clear jelly dripped onto the floor. “Do you see anything? That’s the stuff Perry uses. Whenever I’ve hit [Perry’s greaseball], I’ve just been lucky. If they ever legalized the pitch, everybody in the league would be a .250 hitter.”

Nearby, pitcher Fritz Peterson offered his theory on Perry’s method. Peterson believed Perry put a dab of K-Y over the blue ink stamp reading “Reach,” the brand logo2. “This makes it difficult to detect since it’s on the printed part of the ball.”

Strolling in to the clubhouse, Perry was pleased to see a large cardboard box sitting on his bench. He tore it open with relish. “Well, lookee here. My new hats.” He grinned. “I’m gonna wear a new one for Ralph Houk. He said my other hat smelled funny.”

Houk waved the press away. “I’ve got absolutely nothing to say about Murcer being fined and I don’t care what Perry does tonight. You can bet anything I won’t go out there.”

“Did they fine Murcer?” Perry asked a reporter. Hearing that they had, the pitcher shook his head and tsked in disappointment.

Bobby was just saying that in the excitement. I like him. He’s just trying to win. So am I. I’m sorry he got fined, but I love the rest of it, I really do. I’ve been thinking all day of things I can do to aggravate them some more. Wait till you see what I do when Murcer comes to the plate the first time.

With all the hoopla, the Yankees had hoped for a big crowd, but rainy weather kept attendance just under 10,000 people. The fans got their first look at Gaylord Perry in the bottom of the first, and the pitcher did not disappoint.

As the first batter, Horace Clarke, stepped in, Perry’s long right arm and hand flickered about his torso with indeterminate purpose. He touched his cap, ran his fingers along the visor, then brought them down the right side of his head and behind his ear. As Yankee Stadium erupted in boos, Perry drew his hand across his chest—stopping briefly at his neck—and finally entered his actual wind-up. Clarke eventually drew a walk, but Perry had delivered his message: it would be business as usual that night, no matter who was watching.

Bobby Murcer batted fourth in the lineup, and he walked to the plate that same inning with two outs, receiving a spirited cheer. Perry made a meal of the moment, taking off his cap and giving Murcer and the unblinking cameras a Cheshire smile as he took the ball in both hands and gave it a slow, thorough rubbing. It was an age before he began his routine of twitches and ticks, speeding up so fast that only the cameras could follow. Murcer surely knew all of this was coming, and he absorbed it impassively. He grounded out to second base and returned to the dugout without protest.

The center fielder got another chance in the fourth. By then, Perry had faltered, giving up a solo home run and a single already in the inning. Murcer got hold of another mistake pitch and launched it into the bleachers. “It looked to me like a hanging greaseball,” he said.

Now it was Murcer’s turn to give Perry the full treatment. He took his time rounding the bases, pumping his right arm into the sky and waving his batting helmet to the delighted crowd. This was a lot of show for the 1970s, but Perry took no offense.

The pitcher had nothing, but he kept at it. The next batter walked, then a single, then Thurman Munson, who held up the game twice asking the home plate umpire to inspect the baseball. Munson walked, and with two outs, shortstop Gene Michael cleared the bases with a three-run double.

The Yankees won the rematch, 7-2. Despite his fourth inning unraveling, Perry pitched the entire game and stayed fully in character. “I did the same things I always did,” he said afterward, suppressing a smile. “If people want to read things into it, so be it.”

In the New York clubhouse, an unidentified member of their pitching corps discreetly passed a sheaf of charts to a New York Times reporter. It was a complete, annotated report of every pitch Gaylord Perry had thrown in the game. Spitballs were marked with a “+”, and according to the report, Perry had thrown 30 of them. During the at-bat when Thurman Munson asked for two inspections, the chart showed nothing but “+” signs.

The reporter got in touch with ABC and brought the chart to their New York studios to review the film of the game. Of course, the network had picked up exactly where the Yankees left off, recording Perry’s every movement while on the mound. Comparing the two data sets revealed the pitcher’s method—on that night, at least:

A constant emerged before all of the pitches marked ‘spitball’ on the report: Perry tugged the inside of his left sleeve with his right hand. He did not touch the inside of the sleeve before throwing balls that the Yankee pitcher said were not spitters.

The next day, ABC’s Wide World of Sports showed excerpts of the footage (freezing on the left sleeve “gotcha!” several times) and the interviews Howard Cosell did with some of the warring parties. Cosell asked Bobby Murcer about his chat with the commissioner. “He told me the AL is making a study on Perry,” Murcer said. “I guess they’re waiting for it to be completed before they’ll do anything to stop the guy.”

Asked what would happen if the spitball was ever legalized, Murcer scoffed. “It looks to me like it already is legalized.”

Based on all the evidence, the WWS crew rendered their verdict: Perry was definitely probably cheating.

The Yankees and Indians finally went their separate ways. Perry finished the year with a personal 4-2 record against New York and a 19-19 record overall, with a solid 3.37 ERA and 29 complete games.

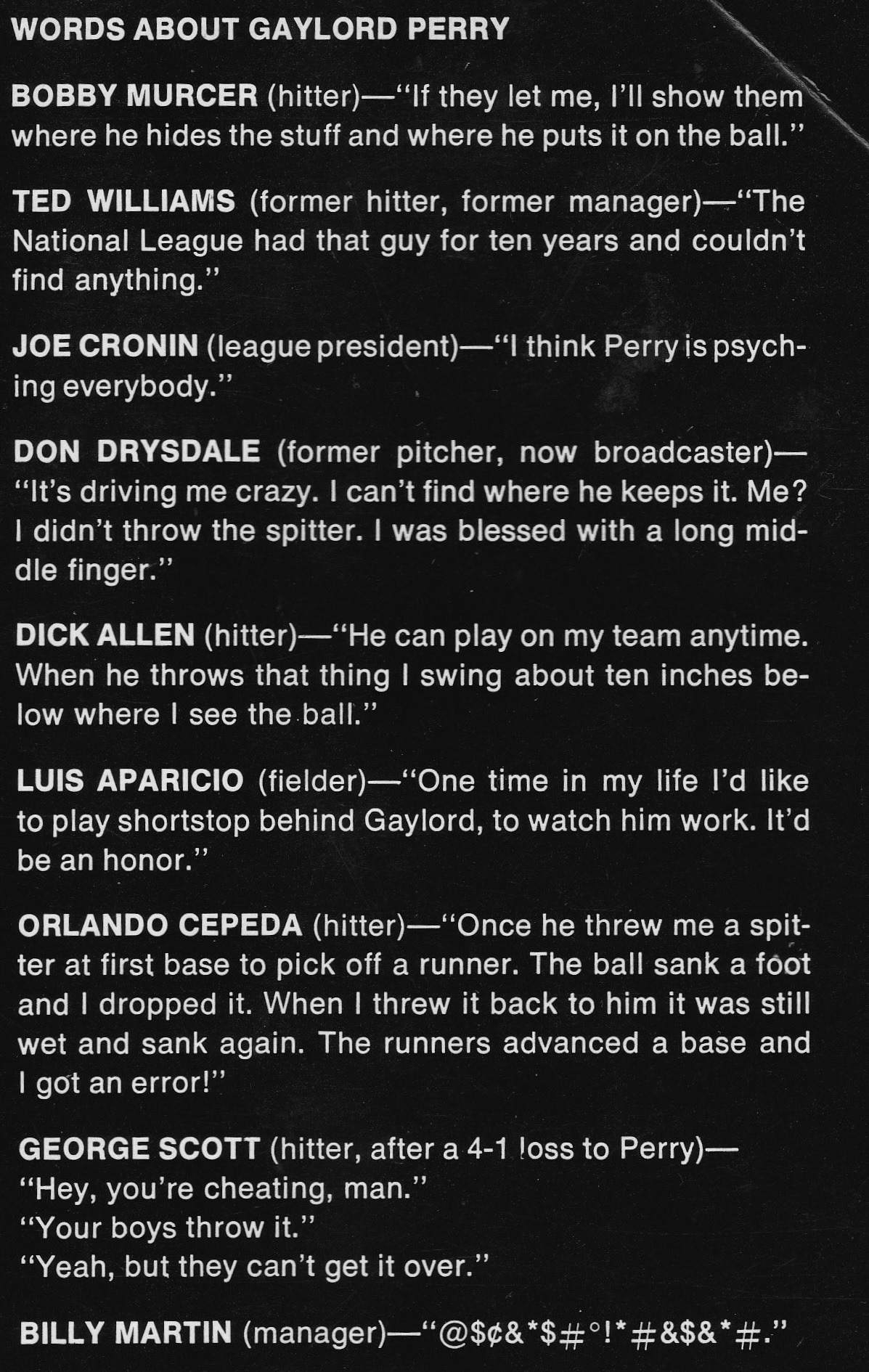

Rather than lie low after escaping the 1973 season unscathed, Perry took his performance to a new medium. He collaborated with a sportswriter to produce the salaciously-titled Me and the Spitter—equal parts autobiography, confessional, and instruction manual—which hit bookstores in early 1974.

The back cover was a particularly good troll, including nonconsensual testimonials from big names around the league, including Joe Cronin and Bobby Murcer:

But even this grand stunt had its tongue somewhere in its cheek. In the book, Perry insisted he was “reformed” and had not thrown any illegal pitches in the past several years.

He patiently corrected reporters who spoke of the book’s revelations in the present tense. “I used to throw it,” he reminded them, “but not in the last four or five years.” A reporter asked when he’d started throwing a forkball. Perry smiled. “Oh, about four or five years.” Branding was everything.

Joe Cronin stepped down at the end of 1973, deciding 47 years in baseball was plenty. He was replaced by a second-generation baseball executive, Lee MacPhail, formerly of…the Yankees. What a small world baseball is. In the wake of the announcement of Me and the Spitter, the two presidents came together to do a little writing of their own.

For the 1974 season, Rule 8.02 was modernized. The old rule mainly described various types of illegal pitches and declared that pitchers “shall not” apply foreign substances to the ball, without saying what would happen if they did.

The new Rule 8.02a filled those gaps in with a very specific offender in mind, becoming widely known as ”Gaylord’s Rule.”

If in his judgment the umpire determines that a foreign substance has been applied to the ball, he shall: a. Call the pitch a ball and warn the pitcher; b. In the case of a second offense by the same pitcher, the pitcher shall be disqualified from the game…

The days of clumsy friskings on the pitcher’s mound were over. Evidence of wrongdoing was no longer required. Suspicion was sufficient.

“I think it’s the greatest innovation in years,” one umpire said. “They’ve finally put teeth into the rule.” Another umpire observed: “Now all the ump has to do is pull the trigger. The manager has no recourse. It ends all the rigamarole.”

That spring, baseball’s foremost rigamaroler3 played it cool. “What about the new rule?” somebody asked him. “I don’t anticipate problems," the pitcher replied, “and I don’t know why you’d ask me such questions.” His feigned indignance teed up a deadpan reply.

“Well…because of the title of your book.”

Perry’s response showed a crack in his veneer of nonchalance. “This is just another rule they’ve put in to chip away at the pitcher’s effectiveness. Lower the mound, tighten the strike zone. All the rules are against the pitcher.” Just another reaching hand trying to take bread out of his mouth.

Gaylord’s Rule claimed its first victim on the very first day of the 1974 season. Somebody made sure that Cleveland opened in New York against the Yankees, and Lee MacPhail got a good seat near the first base dugout. As AL president, he got free popcorn.

The Yankees played their parts. Munson, Murcer, and Graig Nettles began complaining in the fourth inning: The pitcher, Gaylord Perry, was throwing greaseballs.

“He threw me one the first time up,” Murcer said. “The next time he came in with three in a row. That’s when I complained.”

In the bottom of the sixth, the home plate umpire, Marty Springstead, had seen and heard enough. Perry had a 2-2 count on Graig Nettles when Springstead jumped out and called a violation. Perry insisted it was a forkball, but that no longer mattered, the umpire explained:

It’s like a doctor who studies 15 years and makes a judgment if a man has a bad appendix. He makes an opinion that an appendix must come out and then does it. I have been umpiring for 15 years. In my judgment, that was an illegal pitch.

The message had been delivered: Joe Cronin sends his regards.

Nettles eventually walked. “[Perry] showed me a lot of guts,” the third baseman said. “After he was warned for throwing the spitter, he came right back with another one on the next pitch.”

Perry vowed to continue throwing his forkball and objecting to umpires who warned him. “If I don’t, that’s an admission of guilt.”

“Without being able to use the spitter, Gaylord won’t be nearly as effective,” Murcer predicted. “It’s his best pitch and everybody knows it.”

Nettles wasn’t so sure. “When I was with the Indians, I saw [Perry] pitch entire games without doctoring the ball,” he said. “I see no reason he can’t win without it.”

After that Opening Day loss, Gaylord Perry won his next 15 starts, one short of the American League record. He did not lose again until July 8.

It was an all-time performance, or an all-time heist, but after that, the distinction became less important. Greatness was greatness; the rest was just spin.

Did you ever see Gaylord Perry pitch? Tell us about it!

No umpire called two “8.02a” violations on Gaylord Perry in one game until August 23, 1982, when Dave Phillips became the first and only official to eject Perry for throwing illegal pitches. The opposing manager? Ralph Houk. Oh, and it was Seat Cushion Day at Seattle’s Kingdome...so, yeah, more on that in a future piece.

Next week we’re excited to bring you something rather different. It’s a new entry in (what is apparently) a Project 3.18 series on gender, culture, and baseball in the 1970s. We’re going to revisit one of the first groups of women to work on the field in that era, taking us to Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, home of the Pirates…and the “Pirettes.”

On December 2: “On the Lines”

Implying Perry might just opt to skip his start at Yankee Stadium—presumably out of guilt or fear—was a classic bit of Steinbrenner bombast.

“Reach” was a legacy brand name that called back to A.J. Reach & Co., which manufactured National League baseballs until Spalding acquired the company in 1889. Spalding continued using the Reach intellectual property into the mid-1970s.

Not a real word.

Rigamaroler — it’s real and it’s spectacular.

Commissioners; I think that’s a topic in itself that can be viewed under the microscope. I guess it’s just me, lack of knowledge but it seems most if not all are useless figureheads that collect lotsa dough for being idiots. Ridiculous rule changes or carrying grudges I.e. Pete Rose, I think they have too much power.

Have a good Thanksgiving Paul & thank you.