The Garbage Collector

Pete Rose, 1941-2024

At Project 3.18, we hate this part. We’d much rather write about people in the prime of their noteworthy, complicated lives, savoring the moments that will one day pile up into their legacy. But we can’t skip this one. Today, Pete Rose leaves behind one of baseball’s greatest heaps. Here are two moments we covered this year:

1968: The Disallowed

1988: 65 Seconds

We’ll have more stories featuring this unique American figure down the road, but as we join the large chorus singing all the discordant notes of Rose’s life today, there is only one story we want to tell.

In my mid-twenties, I was a writer who didn’t know what to write about. I was spinning my wheels in short fiction and starting to remember what it felt like as a kid in little league baseball when my team graduated to live pitching—that was the first time I could see the ceiling of my own capabilities and gosh, it seemed to be coming up on me rather quickly.

Searching for topics that sparked joy, I thought of baseball, which I loved, but my knowledge at that point was mostly of the present, whatever I’d seen with my own eyes or on ESPN’s Baseball Tonight. There were no secrets there, and the only thing I wanted to do as a writer was to try and surprise, which, I should acknowledge, is a terrible goal for a writer. And baseball was well-covered. Before discarding the idea and maybe the whole thing, I decided to poke around in a few of major league baseball’s innumerable closed-up old cupboards, just to see what was in there.

I don’t remember exactly where or how I found it, but one of my first discoveries was a Pete Rose moment from a World Series I knew nothing about: Game Six of the 1980 World Series between the Philadelphia Phillies and the Kansas City Royals. Going in, I’m not sure I even knew Rose had played for the Phillies, but I quickly came to understand that something truly magical happened that day at Veterans Stadium.

This unexpected find sparked the idea for a whole treasure hunt. What else was hiding in all the baseball I’d never heard of?

Here’s the set-up for this Pete Rose magic trick:

The Phillies lead the Series, 3-2, and the game, 4-1. This was the top of the ninth inning—the Royals’ last chance, but it was a real chance—they had loaded the bases against the Phillies’ beleaguered closer, Tug McGraw. McGraw had arrived back in the eighth inning and loaded the bases before escaping, but here he was, both arsonist and firefighter, having once again put the tying run on base and the winning run at the plate with just one out.

Oh, and I should mention: In 1980, despite being one of the National League’s founding teams, the Philadelphia Phillies had never won a World Series.

With the bases loaded, second baseman Frank White came to bat for the Royals. He was hitting 2 for 24 in the Series, though there was some potential—he had been named the Most Valuable Player in the ALCS in recognition of his 6 for 11 performance, including a home run.

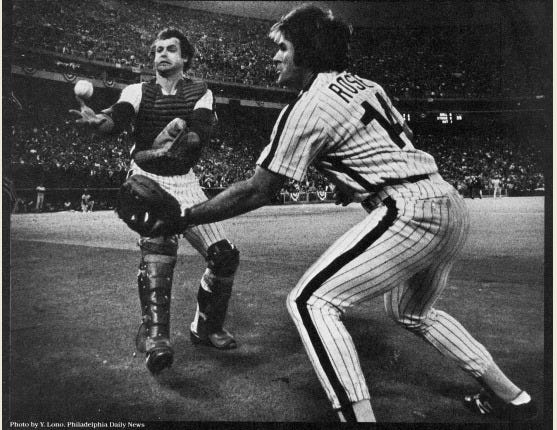

On the very first pitch from McGraw, White skied a pop-up which drifted toward the visitors dugout. Philadelphia’s catcher, Bob Boone, jogged after the ball, his eyes tracking it amid the stadium lights. With the ample foul territory in Veterans Stadium’s baseball configuration, Boone had a play, and hope flared white all over the ballpark. This was the second out.

As the catcher neared the Royals’ open dugout, with no fences between the stairs and the field, he had to think about his body in space as much as where the ball was. Boone shuffled his feet a bit, seemed to briefly stop tracking the ball, then reacquired it. He crab-walked another step into range, but no longer squarely under White’s pop-foul. Out of time and room, Boone extended his mitt out to try and catch it away from his body, and did catch it, but only briefly. The ball caromed away from the awkward catch, with a mind of its own and a determination to reach the ground and keep Frank White’s at-bat alive.

The way baseball mythology works, this errant foul ball was Pandora’s box in cowhide. If a catchable ball like that escaped, extending the at-bat, nightmares (or miracles, if you were a Royals fan) would be unleashed. A similar ball would one day skip toward Bill Buckner’s legs and another would land in poor Steve Bartman’s unwitting hands, blossoming into limitless regret.

If given a reprieve, the scuffling Frank White would surely go on to hit a grand slam, or at the very least a bases-clearing double. The Royals would win the game and tie the series. The forced Game Seven would feel like a public funeral from the very first pitch, that dropped foul ball hanging around the Phillies’ collective neck like a millstone and ensuring one of the National League's founding teams went at least another year without seeing a championship, or even longer.

All this, wound up inside the foul ball that dribbled from Bob Boone’s mitt.

Just as he lost control of destiny, a bouncing figure loomed up on Boone's right. It was the first baseman, Pete Rose, who believed in no mythology but his own. In that tradition, this was not calamity, it was opportunity.

The first baseman had come in to “back up” Boone up on the play. In a routine back-up situation, the second player tracks the ball in flight and loiters nearby, until the primary fielder stakes his claim, and Boone had done that.

Most players would have eased off at that point, but this was Pete Rose, radiating the can-do attitude of a young child helping a sibling open their birthday presents, hovering close enough that Boone could smell his Aqua Velva aftershave. Only because he was that single step away, Rose was able to stick out his own glove, extend his body just over the dugout, and pluck the escaping ball out of the air around knee-height, moving so smoothly that it seemed he and the ball may have been in cahoots the whole time.

In the broadcast booth, color commentator Tony Kubek erupted into a stream-of-consciousness ode to "hustle." Announcer Joe Garagiola was similarly beside himself. "Pete Rose!” he exclaimed, invoking the two-syllable mantra of baseball. “Tremendous play! He's like the garbage collector in hockey, always around the puck, he's always around the ball. What a play!"

In an instant, the nail-biting pall inside Veterans Stadium was wiped away. The rules on this situation were clear and legible to everyone: Philadelphia was going to win.

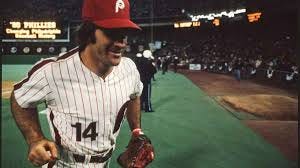

Having never even broken stride, Rose took off running (hustling, some would say), towards the pitching mound, dribbling the baseball off the hard AstroTurf.

"Two outs!" Rose barked as he tossed the ball to Tug McGraw. The two veterans locked eyes, and in that gaze, some further conversation took place, perhaps a pep talk, perhaps some tough love, perhaps a scolding, or all of it, in an instant.

I can’t do this all by myself, Rose told the closer. Now do your job and make a goddamn out.

McGraw made one.

In the championship locker room, Pete Rose oozed aw-shucks-been-there-before charm, leaning into Bryant Gumbel, reporting for ABC: "I knew Boonie had it all the way," he said. "I just didn't have nothing else to do, so I figured I'd go and back him up."

Asked of the catch’s significance, Rose was uncharacteristically mum: “It was the second out, that’s all.” In fact, the catch had put a padlock onto the box containing Frank White, World Series Hero, ensuring it would stay closed forever, but others would have to tell that story.

Nearby, Tug McGraw was as delighted as anyone for Rose’s brief, brilliant side-bar. “That made me feel things were going my way,” the closer said. “Saved me a few pitches, too. I wasn’t surprised that Pete caught it. He does things like that1.”

In 2022, after a long time away, I had another chance, maybe a last chance, to try being a writer.

That summer, I sat in front of a blank document and cracked my rusted knuckles boldly, hopefully, but nothing happened. As a writer, this is a profoundly uncomfortable feeling, best avoided, as I had done for the previous ten years. Looking at that empty screen, staring at nothing and seeing nothing, I wondered if staying away had been the correct choice after all.

I had nearly given up, ready to close my laptop and head for the exits, when a familiar, burly form appeared in my peripheral vision, vibrating with brash, affirmative energy. It was Peter Edward Rose, arriving at the last second and knowing neither doubt or fear.

He popped his chewing gum, bounced the ball once on the chemical carpet, and tossed it to me. I couldn’t tell if he was glaring or laughing.

I can’t do this all by myself, he said. Now do your goddamn job and write something.

He jogged back to first base and waited.

One More Thing

A few months after Rose’s passing, I found a reference to this catch in a 1985 article/interview written by Ira Berkow in the New York Times. Berkow saw Rose’s snag just as I had:

The play was so starkly simple in its beauty, in its execution, and so unexpected. But it demonstrated the essence of Pete Rose—he leaves little to chance.

Berkow asked Rose to reflect on the catch, five years later. Replying “in his direct manner,” Rose dismissed it as business as usual.

What was I supposed to do? Stand at first base with my thumb up my ass?

I encourage you to watch the catch for yourself because we have that privilege. It happens right around the 2-hour 45-minute mark and somehow the whole sequence takes just twenty seconds.

Paul, thank you for not closing your laptop & continuing your writing. We’re all better for that. Chasing your dreams is ALWAYS a good idea.

My family moved from NYC when I was 7. I actually lived about 8 miles from Yankee Stadium which is not my point. Living on Broadway I didn’t play any baseball so when I got to Jersey I didn’t feel I had it in me. Of course I played Wiffle ball & had catches but never got to actually play on a groomed & manicured green field. I always wanted to but never thought my caliber was sufficient. So my point to you is your contribution to do your passion I applaud. By not quitting you’re hitting .300; thanks for continuing.

Ditto!