The National Bird of Canada - Part 2 of 2

Including the weirdest-imaginable idea for a “CSI” spinoff.

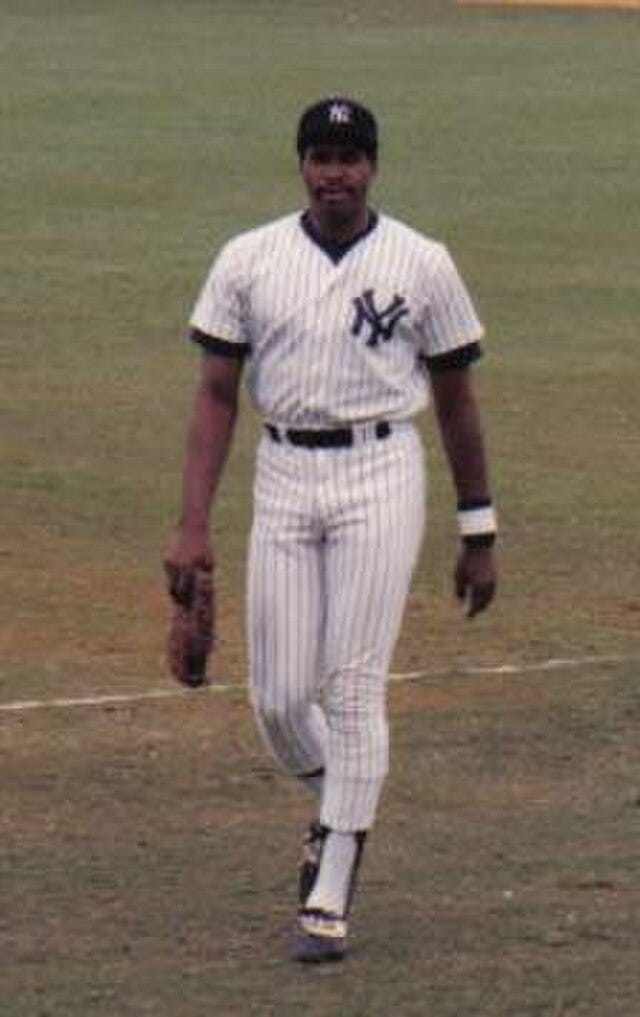

When we left off, one of the New York Yankees’ star players had been arrested for throwing a baseball at a ring-billed gull, a poor choice which led to the bird’s demise. Part 2 of our story opens as the Blue Jays’ front office and Dave Winfield’s Yankee teammates realize that the star was actually being taken to jail.

Here’s the first part of the story:

As the night of August 4, 1983 stretched into August 5, Dave Winfield was taken to Toronto’s District 14 police station to be processed. This step alone seemed egregious, given the circumstances, but the arresting officer, Wayne Hartery, insisted in 2013 that this was standard protocol. He claimed that noncitizens were required to be held in jail until they posted bail, no matter the severity of the charges. Any Canadian legal experts, please chime in in the comments.

Hartery also retrieved the deceased gull from the ballboy who’d collected it, and it now sat in a box on a police officer’s desk, covered in a white towel while, nearby, Winfield was read his rights.

In 2013, Hartery recalled that Winfield had been “a total gentleman” during the booking, without displaying a “big shot” attitude. He was polite, but not necessarily cooperative, declining to participate in an interview without a lawyer present, and can you imagine being the lawyer getting that late-night call from your client?

Back at Exhibition Stadium, the dumbfounded Yankees were in limbo. “I could understand the fuss if it was a blue jay,” said third-baseman Graig Nettles. “But it was just a gate-crashing seagull.”

“How can you intentionally kill a stupid seagull with a baseball from a hundred feet?” Jeff Torborg, the pitching coach, asked. “You want to tell me the odds of that?”

Billy Martin wouldn’t take them. “Intentional? They wouldn’t say that if they’d seen the throws Winfield’s been making. That’s the first time he’s hit the cut-off man all year.”

The Yankees’ manager had made vendettas out of far, far less, and he fumed as the Yankees waited for Winfield.

“I’ll tell you one thing,” he said. “When Toronto comes down to New York next week, we’re gonna get their four starting pitchers arrested. We’re gonna have somebody call the police and say they were molested in the hotel.”

At the District 14 station house, tipped-off reporters photographed Winfield through the windows at every chance, seeking angles that suggested criminality. Meanwhile, the Yankees’ star read a newspaper and waited to post his $500 bail. He had only $200 in cash, so the Blue Jays’ general manager, Pat Gillick stepped in to pay it in full.

Meanwhile, police officers reportedly sang the Blue Jays “theme song1” and made up new topically-relevant verses. The New York Times reported some of the police asked Winfield for autographs2, but we’re not sure we believe that.

Arrangements were made for the gull’s remains. The police planned to work with the Humane Society to—and we swear this is true—have a forensic autopsy3 performed. The bird’s remains would be transported “via veterinary ambulance” to a nearby college laboratory.

Winfield was required to sign a paper saying he or a representative would return for the criminal court hearing, which would take place on August 12. Shortly after midnight, he walked out of District 14. Gillick, deeply embarrassed over the whole affair, drove him to Hamilton Airport. As Winfield boarded the much-delayed charter plane, fellow outfielder Oscar Gamble cried, “Break out the cuffs!”

August 5, 1983 was a long day for Toronto’s civic leaders. The Metro Police were barraged by calls from press across North America, many of whom did not believe the overnight wire reports of what had happened and wanted confirmation that one of baseball’s best-paid players had been arrested for bird murder. Once they verified the details, every talk show, radio show, and newspaper in two countries ran the story, working in at least one bird pun and a joke about how differently things were done in Canada.

Some tried to bring the affair to a quick end. A radio station in San Francisco offered to provide a replacement gull from the city’s stock if Toronto dropped the charges, and another commentator suggested that a target gull be set up and Winfield given 100 baseballs with which to try and hit it—the Blue Jays could do this as a ballpark promotion.

The local authorities, none of whom supported the arrest, were also looking for an out. The police chief said he’d heard that Winfield was being arrested the night before, but “thought it was a joke.” The duty officers had reportedly tried to consult with the Crown attorney (the equivalent of an American district attorney…we think) before formally arresting Winfield, but the lawyer in question, Norm Matusiak, didn’t get the message until after the arrest. Matusiak was supposed to have the day off on August 5, but was called in to somehow unexplode the bomb of international mockery that Hartery had detonated the night before.

That morning, Matusiak huddled with “two senior police officers” to review the evidence in the case. He then released a statement saying that “after a careful reassessment and a lengthy phone conversation with Mr. Winfield,” he would request that the court drop the charges. The bail money the Blue Jays paid would be refunded.

“It’s always a key issue to find criminal intent, and I am satisfied there was none here.”

“I’ve been exonerated,” Winfield said, safely home and working out at Yankee Stadium. “I feel badly about it, but the Toronto police realize it was an accident.” NYPD officers were assigned to follow Winfield around for the next few days, not to protect him from bird-lovers, but from a near-frenzied media.

The Yankees’ owner, George Steinbrenner, requested that the Toronto authorities apologize to Winfield for the “unnecessary and ill-advised treatment” he had suffered. Steinbrenner also filed a complaint with the American League. “This is not the first time that seagulls have come to rest in the outfield of Exhibition Stadium,” Steinbrenner said. “AL teams should not have to play games under these conditions.”

Toronto’s mayor, Art Eggleton (and the jokes really do write themselves in this story), was considering a letter of apology. “I consider the whole incident a regrettable over-reaction,” Eggleton said.

We went overboard on this one, and it sure doesn’t help Toronto’s reputation. I just can’t appreciate why Dave Winfield was taken to a police station. If he went after the bird with a bat, okay, but just throwing a ball? Maybe he was trying to shoo it away, but I’m sure he didn’t intend to kill it.

Toronto Metro Chairman Paul Godfrey was already scheduled to vacation with his family in New York and took it upon himself to embark on a diplomatic mission.

I’ll be at the Blue Jays-Yankees doubleheader in New York on Monday night and, if I can see Dave, I want to say I’m sorry. I don’t believe for a moment a man of his stature and background of human relations skills would intentionally do a thing like that. It was most unfortunate that he was charged.

Statement after statement came out, collectively suggesting that the only person in Toronto government who felt Winfield committed a crime was the constable who arrested him, touching off an international incident in the process.

Diplomats in New York weighed in. Ken Taylor, Canada’s Consul General in the city, sought to tamp down on rampant misinformation: “Everyone seems to think the seagull is our national bird,” he complained, forcing him to explain that, no, the bird in question was not in any way affiliated with Her Majesty’s government.

Hartery was never disciplined for arresting Winfield, and his superiors were careful to say that, technically, he had done nothing wrong. He’d seen someone kill a bird with a baseball, and this seemed to technically constitute sufficient probable cause for detaining them. Then and now, however, it is still not clear why the constable chose to take this rather extraordinary step.

From there, the rest of the system failed as no one in the chain of command intervened to deescalate the high-profile situation until after Winfield had been charged and the headlines became inevitable.

Of course, somebody called Dave Winfield’s mother to get her take on all this. Arline Winfield said her son had “enough problems playing baseball without being subjected to a stupid charge.” The incident was “the silliest thing I’ve heard. My goodness, people hit deer with their cars but aren’t treated like criminals.”

On August 9, Metro Chairman Godfrey conducted his doubleheader diplomacy at Yankee Stadium, meeting privately with Winfield in between games.

“I’m not here to satisfy George Steinbrenner,” Godfrey said.

I wanted to speak to Dave because I don’t think he got a fair shake. A lot of us feel that way. I think the whole incident shouldn’t have taken place. I told him we were most distressed about the whole series of events. He’s prepared to let bygones be bygones.

Winfield briefly and reluctantly spoke to the media. “I appreciated the apology. I don’t think anybody came out of this looking very good.”

Meanwhile, in Canada, the autopsy results confirmed the gull’s cause of death. It had been hit in the head with a baseball.

However, in 2013, a Toronto Star journalist got more details from Ian Barker, the wildlife pathologist who examined the bird, and the information might have been enough to exonerate Winfield in court, had the case gotten that far. Remember the reports that the bird “didn’t look right”?

“It was a juvenile in thin body condition,” Barker stated.

My assessment basically was, it had microscopic evidence of Aspergillus4 in the lung…animals with suppressed immune systems are more prone to developing that. It had reduced muscle mass, no fat, one of these young birds that was going to die within a week or 10 days. There was a little bacterial infection in its wing, a number of things that were going on. It was a debilitated bird.

Such an ailing bird would have struggled to get out of the way of even a casually-thrown baseball, making the possibility that the bird died by accident much more plausible. What is the Canadian standard for reasonable doubt?

The evidence was never tested in court, because crown attorney Matusiak showed up at the August 12 hearing wearing a seagull lapel pin and successfully petitioned for the charges against Winfield to be dropped. The hearing took about a minute.

The gull pin was a nice touch, but it did not forestall the inevitable second wave of complaints from the region’s myriad ornithological societies and unaffiliated bird-fanciers in two countries, lumps the Toronto government was all too happy to take, considering the alternative.

We wish we could write that Toronto’s gulls received a moment of triumphant catharsis following the incident, perhaps becoming the national bird that many Americans, including Winfield, incorrectly assumed they were. But this was not to be. Canada didn’t receive a national bird until 2016, and when it did, the ring-billed gull didn’t even make the top five5. The winning bird was the grey jay, now known as the Canada jay.

A New York baseball player had accidentally stumbled into a Canadian ecological quandary. In creating the Leslie Street Spit, Toronto’s humans had inadvertently set up a near-perfect seabird production facility, leading to an airborne invasion of the city’s nearby recreational spaces. The first shot of this conflict came via the questionable throwing arm of Dave Winfield, but Toronto soon realized that war was both inevitable and probably necessary.

The same day that the Winfield charges were dropped, alderman Tony O’Donohue of Toronto’s Ward 4 complained that gulls were “fouling” beaches and parks.

“Gull and goose populations have mushroomed in the past few years. They’re literally driving us out,” O’Donohue said. He requested that the city government hire ornithologists who could figure out how to put the birds on some kind of birth control. This sounds ridiculous but is actually part of what such professionals do.

As the area’s population went from 10,000 birds to 200,000 in less than a decade, animosity to gulls went mainstream. The Toronto Star polled readers and half were in favor of population control. “Bring back Dave Winfield,” one respondent suggested. By 1985, mood had swung far enough that one regional mayor declared war on “the rats of the air.”

The Toronto Regional Conservation Authority began efforts to manage the population around the same time. “Gulls used to nest in three areas [of the Spit],” Karen McDonald, a former TCRA employee, told the Star in 2013. “We only wanted them to nest in two, so we took one area and oiled all of the eggs (birth control!)” Until vegetation could secure the reclaimed site, officials installed fake predators, including a coyote hide draped over a sawhorse. Once the city took steps to manage the gulls, their population on the Leslie Street Spit fell to roughly half of what it had been, around 70,000 birds.

McDonald felt that the Winfield incident had probably contributed to the change in public sentiment. As much as the city (briefly) rallied around the one lost bird, that the bird was there in the first place led to an appreciation of the larger problem of gull overpopulation and the necessary public will to do something about it.

In this story, the cathartic ending goes to Dave Winfield. He and several Yankee teammates returned to Toronto in the offseason, accepting invitations to participate in the Conn Smythe Sports Celebrities Dinner, benefiting the Easter Seals Society.

Having done his time the previous summer and now returning to town wearing a tux, Winfield told the audience he’d been on quite a journey. “I feel like a mosquito in a nudist camp. I hardly know where to start.” He assured the audience he’d come of his own free will and was free to leave at any time.

In addition to giving little speeches, the players were asked to contribute something to be auctioned off for charity—autographed bats, memorabilia, etc. Winfield opted for a grander gesture. He “owned a couple of art galleries” at the time, so he commissioned a painting.

The inscription read:

To the Canadian people, committed to the preservation of their values and resources.

The painting sold for approximately $30,000 dollars.6

Though he was exonerated, the gull incident nonetheless became a key anecdote in Winfield’s Hall-of-Fame-level iconography. Fans in Toronto would flap for him whenever he returned to visit. Things changed nine years later, in 1992, when Winfield signed a one-year deal with the Blue Jays and became a key component in the team’s first World Series title. Winning with “Winnie” turned the flaps into claps, and all was at last forgiven.

Well, unless something surprising happens in the coming days, we think that’s it for bird stories for a while. Let us know if you hear of anything.

Next week, we’re going to tell the story of a truly unexpected event: the Mets and Cubs game at Shea Stadium on July 13, 1977, when all the lights went out.

On August 19: “Blackout Baseball”

One More Thing:

We love oral histories at Project 3.18, and Katie Daubs’ 30th anniversary retrospective on the “most absurd episode in Blue Jays history” was an invaluable source for this story. It’s free online and full of gems we didn’t get to include. If you can access the original paper, though, you’ll be rewarded with some wonderful visual artifacts, including the gull-themed insignia patch the officers at District 14 created to commemorate their most high-profile case.

We do not know what this might refer to, but if you can point us in the right direction, leave a comment!

Hartery later said he regretted not asking for Winfield’s autograph while he’d had the chance.

In these circumstances, conducting an autopsy seems rather extravagant, but in cases where suspected animal abuse occurs behind closed doors (often with pets), authorities rely on such procedures to provide evidence of the crime.

A common type of fungus (mold) that can cause trouble in the airways of both people and (evidently) birds with weakened immune systems.

The grey jay, snowy owl, common loon, Canada goose, and black-capped chickadee made the podium.

We assume that is Canadian dollars. Can we go home soon?

A word of defense on behalf of Constable Hartery. Putting aside the question of whether he overreacted, and giving full credit to Winfield for his post-incident comportment, I would tend to believe Hartery when he says he overheard Winfield say “watch this” and I understand why Hartery would be disgusted by what happened next. There doesn’t seem to be any reason for Hartery to just make this up. And while it’s doubtful Hartery knew it, Winfield had previously demonstrated a taste for taking a cheap shot (or five) at a vulnerable being: https://vault.si.com/vault/1972/02/07/an-ugly-affair-in-minneapolis. That doesn’t come close to proof beyond a reasonable doubt, but a failure to cross the high bar for finding Winfield guilty of a criminal offense is not the same thing as saying Winfield, who seems to be a basically decent guy with a streak of menace mixed in, is innocent of what Hartery accused him of.

I don’t know if we can entirely rule out suicide in this case. As you pointed out, the bird was ailing and likely to die soon. Perhaps he opted for “death by thrown baseball” as a solution (similar to “death by cop”).