The Night They Caught Gaylord - Part 1 of 2

After a 20-year manhunt, baseball’s most notorious spitball pitcher was finally brought to justice.

If we had to pick our favorite player in baseball history, we’d have to think about it, but the answer might be Gaylord Perry. Somehow this one man managed to be a legitimately great pitcher, a master of deception, and a kind of baseball Robin Hood who flaunted the rules in plain sight, making his pursuers look like bumbling amateurs. We’ve previously covered Perry’s slippery antics here at Project 3.18, and writing that story, we were hooked.

How could we not love a psychological maestro with a wicked sense of humor, a towering ego, and a persecution complex so well rehearsed that even he came to believe it? Perry was determined to succeed, even if that meant throwing a pitch that was technically illegal from time to time. It’s worth remembering that not everyone agreed the “spitball” should be an illegal pitch. It took real skill to throw; as much as a looping curve or a dancing knuckler. Perry wasn’t just someone with morals flexible enough to play with a cheat code; he was a hardworking craftsman, a true artist.

He was many things, was Gaylord Perry. But he wasn’t perfect. On August 23, 1982, he finally screwed up.

According to official records—and his own recollection—the first time he was ejected, the offense was “bench-jockeying.” Like so many things with Gaylord Perry, that was true, if misleading.

On April 16, 1970, while with the San Francisco Giants, Perry was seated on the Giants’ bench when an umpire, Chris Pelekoudas, called a balk on his teammate, a rookie named Jim Johnson. Perry disagreed with the call and reportedly “bellowed too long and too loud” for Pelekoudas to ignore, and the umpire sent Perry to the locker room.

But there was bad blood between the pitcher and the umpires working that series. The trouble really began the day before, on April 15, when the Pelekoudas and the rest of the umpire crew “acted like a police dragnet” trying to catch the game’s most elusive cheater.

Twice during that game they stopped play to examine the ball and Perry’s arms and wrists. After a pitch to Houston’s John Mayberry, three umpires swarmed to Perry’s location. Home plate umpire, Dave Davidson shouted for the ball, which the catcher had already thrown back to Perry. With the instinctive nonchalance and dexterity of a pickpocket, the pitcher brought the ball over the fabric of his pant-leg as he tossed the ball to Davidson. The officials howled, telling Perry not to wipe down a ball they wanted to inspect, but it was too late. No one believed he was innocent, but with no evidence on the ball, he was found not guilty.

“We found some type of lubricant on his forearm, from here to here,” umpire Augie Donatelli said, pointing to his inner forearm. “We made him wipe it off and told him we would throw him out if he went from his wrist to the ball again. He didn’t do it again.”

After the game Pelekoudas defended the sting operation. “The ball does tricks and when it does you’ve got to check it,” he said. The officials claimed to have seen “at least eight or nine pitches” displaying the characteristics of an illegal “spitball” or “grease ball.”

The next night the umpires defended themselves against charges that they were singling Perry out. “It was obvious he was using something,” Pelekoudas insisted. “We reported it to the league office and the president [Chub Feeney] said he’ll back us up.” Pelekoudas reminded reporters that a few years prior, he’d been involved “in a similar incident1” at Chicago’s Wrigley Field, when a different president, Warren Giles, “didn’t give us much support.”

The Feeney administration seemed more interested in law and order. “We’re going to be bearing down on anybody using anything illegal.”

The umpires remained frustrated and twitchy, and after a balk call on Jim Johnson they heard Perry’s voice from the dugout, loaded with criticism. The rules around “bench jockeying” were much easier to enforce, and Perry got his ejection, if a day late.

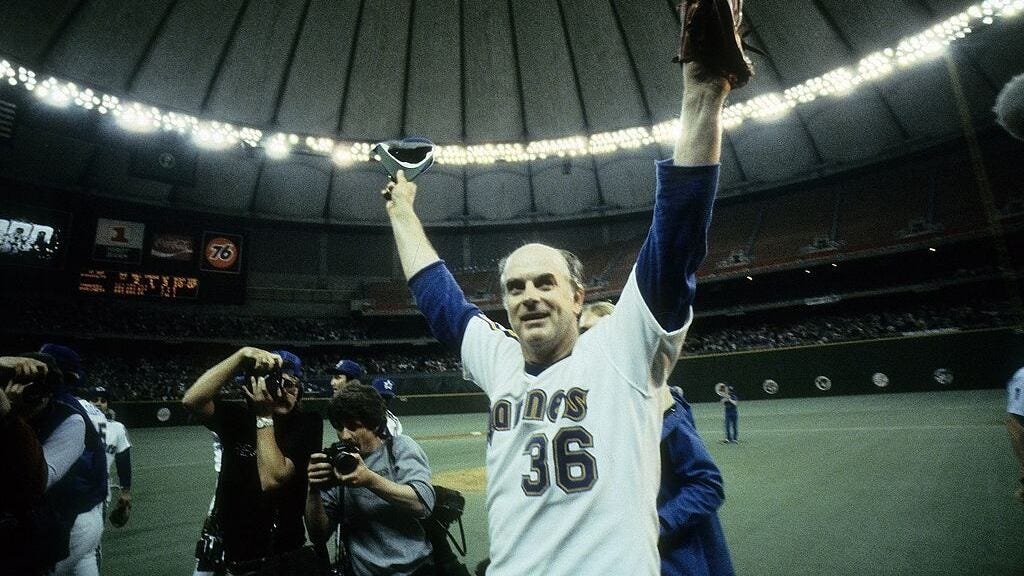

In 1982, Gaylord Perry was 42 years old. It had been more than a decade since his first and only ejection. He remained a paradox, maintaining the physical shape required to pitch competitively while looking far older than he actually was. Pitching for the Seattle Mariners, the 7th team who’d availed themselves of his controversial services, Perry became “the Ancient Mariner,” right out of 18th century poetry, adored by Pacific Northwest fans and grudgingly respected by everyone else.

He was no longer an outlaw—he was an outlaw king whose life of crime had led him not to ruin but to legitimacy, even greatness. He stalked with impunity through clubhouses increasingly populated by awed teammates who had followed his early exploits as children.

Perry had recorded nearly as many strikeouts as Walter Johnson, pitched more innings than Christy Mathewson, and won as many Cy Young awards as Bob Gibson, earning one in each league. On May 6, 1982 he became the 15th pitcher in major league history to win 300 games2, the first to reach that milestone in nearly two decades.

He continued to throw “the spitball,” but refused to permit his catchers to call it that, insisting on referring to the pitch as a special kind of “forkball” (a legitimate pitch he threw) or a “super sinker.” His primary catcher in Seattle, Rick Sweet, later said that he didn’t know what substance Perry was using or how, exactly, he got it on the ball. All he knew was the secret sign the pitcher would use to tell him when to prepare to catch the spitter and another to tell him when the ball was back to normal dryness.

Sweet said the toughest part was the fact that Perry had so many pitches, legal and otherwise. “He would add and subtract with the swipe of the glove and you just better know what number six was,” he told writer/historian Kevin Czerwinski in 2021. Other catchers who caught Perry said he tended to use a combination of legitimate pitches and homespun psychological warfare to get hitters out, but if a pitch stopped working or he got in trouble, the “Super Sinker” would enter service.

As the summer of 1982 heated up, so did the scrutiny on Perry. In the early-season batters seemed more tolerant of a Vaseline ball here and there, but once the pennant races got underway it became harder for opposing teams (and the officials who endured their complaints) to swallow Perry’s flagrant rule violations, both real and imagined.

On August 7, the California Angels played the Mariners in Seattle at the Kingdome. The Angels, virtually tied with the Kansas City Royals for first place, needed every game, and on this night they had to go through Perry. After a big swing-and-miss in the sixth inning, Angels slugger Reggie Jackson made the dreaded “swivel,” turning his body in the direction of the home plate umpire to protest the pitch. The ball had not ended up where it should have, Jackson complained.

The umpires were tired. They had checked numerous baseballs after Angel complaints and every one was thrown back to Perry—clean. But Jackson kept pushing and quickly pushed too far. He was thrown out for arguing, while Perry watched impassively, his hands on his hips. Jackson was not gone long. He returned carrying a bucket of ice water, marched to the mound, and dumped the liquid, reportedly yelling “Use this!”

Perry watched the demonstration with barely suppressed delight.

“I think he does it just to frustrate me,” Jackson said after the game. “I’ve been ejected before in the same kind of situation.”

The heat continued to rise. On August 13, Minnesota Twins manager Billy Gardner made an impassioned plea to the umpires working a Perry start at the Metrodome. On August 18, an umpire named Bill Kunkel tried stalking Perry like a predator, sneaking in behind him and demanding to inspect the ball just as the pitcher went into his windup. He caught the pitcher by surprise—and found nothing.

In a career of remarkable numbers, here was the most unbelievable number of all: 0. During his two-plus decades in major league baseball, Gaylord Perry had never, not once, been ejected for throwing an “illegal pitch.” He had been warned many times, surely more than any other player in history. Whole rules had been added to the baseball rulebook to empower umpires to stop him. As we saw in our previous Perry story, teams installed cameras to surveil him with unblinking electric eyes. He’d been made to throw bullpen sessions in front of a panel of umpire officials to prove his innocence. But despite spending nearly his whole career atop baseball’s Most Wanted list, his official record was spotless. Nearly 100,000 pitches. Zero ejections, zero fines, zero suspensions.

Meanwhile, dozens of hitters like Reggie Jackson were thrown out for the crime of reporting (a little too theatrically) their own victimization. As they were led away, their tormentor just smiled a little smile, touched his fingers to the underside of his cap or the back of his neck, and went right to work on the next guy. He seemed untouchable.

In 1982 Dave Phillips was 38 years old, still on the younger side of his career but already a respected umpire crew chief. He’d begun umpiring in 1971 and had survived a decade going toe-to-toe with a Murderers’ Row of American League managers, anchored by Billy Martin, Dick Williams, and Earl Weaver. Along with his thick skin he had a reputation as a stickler; he was not a “let it slide” guy, even when doing so might save everyone a lot of trouble, most of all himself.

Phillips and his crew had spent August 23 traveling to Seattle, where they were scheduled to work a night game between the Mariners and the Boston Red Sox. The travel was a slog and they had no time to even freshen up before heading to the ballpark.

At the Kingdome, Phillips, who would be working behind the plate that night, checked the starting pitchers, looking for one name and hoping not to find it. A long day got even longer—Gaylord Perry was starting.

“We hated it when Perry was pitching,” Phillips wrote in his 2004 autobiography, Center Field On Fire, “because there was always a possibility there would be problems. Batters were going to ask you to check the baseball, and even if he wasn’t throwing a spitter, he was going to go through the motions and the shenanigans and make the hitters think he was throwing it.”

There was friction almost immediately, according to Perry, who said the ump started it: “You know how umpires roll the ball out to the mound before the first pitch? Well, I’m in the dugout, standing for the national anthem, and Phillips rolls the ball out. I’m getting ready to pitch and he says ‘You like ‘em a little dirty.’ I say, ‘All pitchers like ‘em dirty.’”

In the first inning, the Ancient Mariner was pitching to the Ancient Red Sock, Carl Yastrzemski. Phillips called two balls that Perry thought were strikes.

“[Those were] good pitches and I wanted them,” Perry said. He called out to the umpire: “Hey, I got as much time in the major leagues as he does. Those were strikes.” Yastrzemski walked.

As he walked to the dugout after retiring the third out, Perry said Phillips confronted him. “He says, ‘You think I won’t call a strike on Yaz? You keep your bleeping bleep on the mound. And keep your bleeping mouth shut.’”

“Perry questioned a pitch or two,” Phillips said later. “They both possibly could have been illegal pitches, but I gave him the benefit of the doubt. They both dropped out of the strike zone. I don’t carry grudges.”

As the game proceeded it became clear that Perry didn’t need any help from an umpire. He was having a good night, yielding just one hit through four innings. Such a performance triggered the Perry Paradox. His catchers said he tended to stay away from his Super Sinker when he was doing well without it, but the hitters who faced him on his good days saw spitters flying everywhere.

The Red Sox’ manager, Ralph Houk, who had long been victimized by Perry’s feats of misdirection, joined his players in appealing to Phillips for relief. “[Houk] said, ‘I don’t want to bother you, but it’s getting ridiculous.’”

“He was throwing it eight out of 10 pitches,” Houk said. “That’s the first time I’ve seen him throw it that much. I’m a fan of Gaylord’s but I had to complain because the game was getting to be a farce.”

Phillips kept checking. Whether or not there were hard feelings from earlier, it’s clear that the Red Sox were demanding action and he was doing basically the minimum necessary to satisfy them. The requested checks turned up nothing and did little more than give Perry a chance to put his hands on his hips and look aggrieved.

The score remained 0-0 going into the top of the fifth inning. Perry was warming up, with the Mariners’ primary backstop, Jim Essian, who was catching him that night. The first Boston batter would be Reid Nichols, a light-hitting bench outfielder making a fill-in start. Watching his teammates fall to what they complained were spitballs, Nichols said a Biblical passage, Isaiah 54:17, flashed into his mind: “No weapon formed against you shall prosper.”3

Accounts vary slightly on the timing of what happened next. Phillips says the interaction took place during Perry’s warm-up throws, before Nichols’ at-bat began, but other accounts report it happened during the at-bat, with a full count on Nichols. It’s a relatively minor discrepancy, and no matter when it happened, Nichols asked Phillips to check the baseball again.

Sighing, Phillips asked Essian, the catcher, to let him see the ball. Essian complied without protest. Perry was waiting on the mound, looking annoyed but not concerned. Phillips performatively turned the ball around in his hand, more to satisfy Nichols than in an effort to discover any damning residue. And then, there it was.

“All of a sudden I noticed my fingerprint on the ball. I could see my fingerprint in grease.”

“Almost in shock,” Phillips lifted his head to meet Perry’s impatient gaze. There was a split-second where he could read Perry’s face and in it he saw the truth. The umpire started for the mound. He’d gone just a few steps when Perry recovered enough to slap on the mask of indignant outrage that he carried everywhere he went. He threw his arms in the air. “I didn’t put anything on the ball!”

“When you walk out to Perry on the mound, the smell is medicinal,” Phillips said later. “It was like walking into your kid’s room when they had a cold and they had Vicks rubbed all over their chest. Your eyes always got kind of watery when you got near him because he had so much Vicks on him. Even on the coldest day, he’s sweating, or at least covered in some kind of moisture.”

Billy Martin, who loathed spitball pitchers and Perry especially (except when Perry was pitching for his team in 1975), said something similar: “He smells like a drug store.”

Phillips trudged into the vapor zone, with the Mariners’ manager, Rene Lachemann, hot on his heels. The umpire showed Lachemann the ball.

“I don’t know how this grease got here,” he said to Perry, “but it’s here, and consider this your warning. If anything appears at any other time during the game, or I deem you have thrown an illegal pitch, you will be ejected.”

Phillips received no argument. The pitcher brightened, looking relieved. That reaction told the umpire that Perry, caught wet-handed, had expected to be thrown out immediately. But even with a greasy fingerprint there for all to see, he’d gotten away again.

Reid Nichols finished his at-bat by grounding out, but he’d nonetheless put an enormous crack in Perry’s wall of plausible deniability. Realizing this, the pitcher appeared to take Phillips’ warning seriously—for a while.

“Gaylord didn’t throw any more spitters in the fifth or sixth innings,” the umpire said.

“But he also started getting hit.”

Next week, Gaylord Perry is forced back into his bag of tricks and finds Steve Phillips waiting inside.

On January 19: A doozie of a quick-dipping downer.

Over on Clear the Field:

Did you know that most podcasts don’t last more than 12 episodes? Apparently it’s a major point of separation. To make sure we came out on the other side, Ted and I broke out the big guns—literally. This week we’re talking about World War II, scrap metal donation drives on the home front, and how New York baseball crowds pitched in and ran amok.

The “similar incident” put Chris Pelekoudas in the Project 3.18 Hall of Fame.

When he became a member of the 300 Club, Perry began wearing a T-shirt (also for sale for $7 during his frequent appearances at baseball collector shows): “300 victories is nothing to spit at.”

Isaiah 54:17 was a particularly ironic Biblical verse to inspire a batter facing Gaylord Perry. The next line reads: “And every tongue that accuses you in judgement you will condemn.” Like Jules Winnfield in Pulp Fiction, this would have been a perfect line for Perry to recite to complaining hitters just before he finished them off.

A couple of days ago I advocated on Gaylord’s behalf in response to Mark Kolier’s post about the Giants all-time starting five rotation. I have always thought Gaylord’s reputation suffered—if you can even say that about a hall of famer—as much because the Giants couldn’t quite get over the hump when he was there as because of his reputation for playing fast and loose with the rules. If the Giants had won a couple of World Series title instead of finishing second with 95 or so wins, I believe Gaylord would be held in higher esteem. America loves a champion. Furthermore, it seems like a not insignificant percentage of players in all professional sports take some liberties, and drawing lines can be a little arbitrary. (Is throwing the occasional doctored ball worse than a basketball flop?) That Gaylord threw spitters isn’t something I am just learning of, but I have to admit, when the vagaries of his misdeeds are made more concrete like this, I find myself leaning some in the other direction about his spot in the pecking order. What if you discount Gaylord’s accomplishments by some smallish percentage for his misdemeanors? Does that bump him off the list in the event of a close call?

Mark’s stuff is great. Your stuff is great too. I know you read each other’s great stuff. Curious how you each factor that into the equation.

Gaylord Perry was always “good copy.” Much more entertaining than his brother, Jim, who logged more than 200 wins.