The Philadelphia Signal Service

The first electrical sign-stealing scandal happened when?

In 1987, writing about a trend of scofflaws and ne'er-do-wells scraping up the ball and hollowing out the bat, the writer Thomas Boswell asserted that cheating had always been a part of the baseball. To prove it, he shared an anecdote dating back to the presidential administration of William McKinley, in which a major league team devised a cheating scheme as brazen as it was cutting-edge. That’s our story today.

Around the same time that this story takes place, a British expatriate in the United States could not help but appreciate the current of larceny running through the American game. “You have such jolly funny morals in this bally country,” the man observed. “You steal and rob in baseball and yet you call it fair.”

But even America’s jolly funny morals had their limits, and in 1900 the Philadelphia Phillies staged a heist that was practically criminal.

Usually referred to as “signs,” battery signs are the non-verbal signals between the catcher and pitcher that coordinate the next pitch to be thrown. Such signs are baseball’s version of Top Secret intelligence, and if they fall into the wrong hands, the hands of the batter, he receives an enormous advantage, as per this 1900 explainer:

When a batter knows a curve ball is about to be pitched he can step into it and hit it much better than when guessing what is about to be delivered; he can also stand up to the plate better and meet a fastball if he knows that is coming.

Given their inherent value to both sides, as sign systems developed, so too did efforts to decode, or “steal” them. Sign-stealing has long occupied a grey area in baseball, its ethics debated across three different centuries. Here is the position of Christy Mathewson, one of the First Five Hall-of-Famers and the first National League pitcher enshrined, from his 1912 book Pitching in a Pinch:

I shall divide the subject of signal stealing into half portions, the honest and the dishonest halves.

The honest methods are those requiring cleverness of eye, mind, and hand without outside assistance. Dishonest signal stealing might be defined as obtaining information by artificial aids.

To illustrate just how far dishonest players could go in their efforts to acquire the goods, Mathewson cited “one of the most flagrant and, for a time, successful schemes, which occurred in Philadelphia, several years ago1.”

In 1900 the Philadelphia Phillies (or the Quakers; up to you) played at what was then called National League Park, or Philadelphia Park. Whatever you called the park or the team that played there, this was a relatively modern facility. After an earlier incarnation burned down in 1894, the park was rebuilt with brick and steel and concrete, and was the first facility built with a cantilever system that removed many obstructive support columns from the seating areas. With spacious foul territory and a cutting-edge drainage system, the park should have been a pleasure to play, but by 1900 opposing teams dreaded their visits. National League Park seemed to turn even the most talented visiting pitchers into pumpkins.

Part of that was the Phillies’ good hitting, with future Hall-of-Famers at three positions. But neither Ed Delahanty, Elmer Flick, nor Nap Lajoie was the team’s best weapon that season. Their unlikely MVP was a third-string catcher named Morgan Murphy, who appeared in just 11 games.

Murphy’s background is appropriately shadowy. His major league career began inauspiciously in 1890 and went downhill from there, reportedly as his waistline expanded. Still, teams kept signing him.

The Phillies acquired Murphy in 1898. At 33 years old, he did his thing, batting below .200 and appearing in 25 games. In 1899, he was removed from the Phillies roster but remained a presence at National League Park, where he would warm up with the team but disappear as play got underway. The Phillies had realized that Murphy didn’t have to play. All he had to do was watch.

“He had the eye of a beagle,” a teammate remembered, “and his wits were so sharp they cut him when he lay down to sleep.” His eyes and his wits made Murphy a genius at stealing signs, a codebreaker par excellence.

In 1900 the team rostered him again, but he did not appear in a game until early August and was rarely spotted in the dugout. When Murphy did show up, his presence could be disruptive, as noted in a game account from June 6.

That day’s contest against the Pittsburgh Pirates was “painfully drawn out,” with four innings taking nearly 90 minutes as the Pirates “tried everything they knew to prevent Morgan Murphy from tipping off the signals.” Pittsburgh eventually jury-rigged an entirely new set of signs, resulting in several wild pitches/passed balls, but the system fooled Murphy long enough for the Pirates to fend off the Quaker hitters and come away with a win.

While Murphy had been “away from the team” in 1899, the Phillies added another part-time player after he performed well on their spring training practice squad. He was old for a rookie at 32, but Pearce Chiles, often referred to as “Petie,” was a capable player that year, used mostly on the infield corners. Unfortunately he was stuck behind Hall-of-Famers on the team depth chart and could never break through.

While Morgan Murphy might be considered a kind of baseball shark, merely doing what he was obviously created to do, Pearce Chiles was your garden variety career criminal, a bad dude with the rap sheet to prove it. With the Phillies, though, he seemed to have been an enthusiastic teammate who was often used as a coach, helping manage the offense from behind the third base line. This role also put Chiles at the center of any sign-stealing operation, in which it would be his job to convey pilfered signs to the batter, typically via code-phrases hidden in a steady stream of patter and encouragement. Discretion was essential; as the June 6 game against Pittsburgh demonstrated, stolen signs lost all value as soon as they were reported missing.

With Chiles on the coaching lines and Morgan Murphy lurking out there…somewhere, baseball’s Butch and Sundance2 quickly made National League Park the friendliest home park in sports.

By the middle of September the Phillies had one of the best records in the National League, boosted by some eye-popping home/road splits. At home, the team had a 45-23 mark, winning two-thirds of their games. Playing anywhere else, they were 10 games under .500.

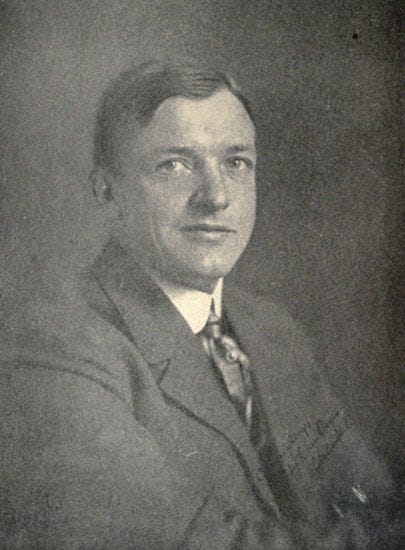

On Saturday, September 15, the Cincinnati Reds arrived in Philadelphia to play five unhappy games against the Phillies on their home grounds. That day, the Reds’ manager, Bob Allen, received some intriguing information. Morgan Murphy was stealing signs—that was self-evident—but according to Allen’s anonymous source, the team was using electrical means to convey the stolen goods to Petie Chiles in the third base coaching box.

Allen promptly began an investigation. “I called on [Phillies manager] Bill Shettsline at his clubhouse on some pretext and then kept my eye skinned for wires. There I detected two running into an upper window.”

The Reds decided not to press the matter that day and lost the game, 6-5. Now that they knew where to look, the entire team put Chiles under surveillance. The part-time coach only worked at third base and was particular about standing in one specific spot. That was not excessively fishy—then and now, ballplayers are creatures of habit—but it was strange that the spot Chiles favored was always wet. Visiting coaches tended to avoid the puddle, but Chiles seemed to have no problem with damp socks. It was also observed that the coach seemed to have a sporadic, nervous twitch in that same leg.

Allen huddled with Tommy Corcoran, the Reds’ shortstop and team captain. Something was clearly going on out in that box, and Corcoran was told to get to the bottom of it.

“Corcoran started to dig into the box,” Allen said. “He did this gradually, in order to avoid detection. Every inning he got a little deeper until he finally struck a board.”

Corcoran had been digging with the spikes of his shoes, but now he abandoned discretion and dropped to his knees, plunging his hands into the mud and dirt in an effort to find the edges of the board and pull it out. Seeing this, several Phillies began shouting objections, and the groundskeeper, a man named Schroeder, came out with a Philadelphia police officer in tow. Schroeder reportedly tried to shove Corcoran off, saying the board was covering a drain outlet. He threatened to have the Cincinnati captain arrested for “malicious destruction of property.”

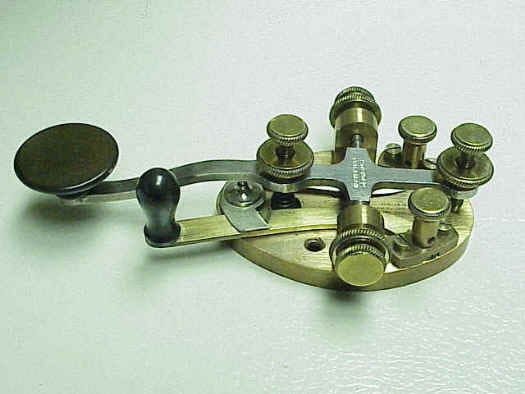

But it was too late—Corcoran found the edges and pried off the top of what turned out to be not a drain, but a wooden box buried in the ground. Inside was a device later described as a “buzzer.”

The buzzer was a modified telegraph sounder, the receiver that made sounds from the electrical current traveling through a telegraph wire. The Phillies’ device had been modified so that when the sounder was triggered, part of the instrument would rattle or vibrate against the lid of the wood box, just an inch below Petie Chiles’ perpetually wet foot.

Arlie Latham, the Reds’ coach, had been preparing to do his own coaching when Corcoran made the discovery. Latham was also a noted baseball comedian. “What’s this?” he cried, playing to the crowd. “An infernal machine to disrupt the noble National League?”

Next on the scene was umpire Tim Hurst, who had a chronic aversion to paperwork. Seeing the Phillies’ “infernal machine,” he suggested everyone forget it and get back to work, flavoring his remarks with a period-appropriate reference to the recent Spanish-American War:

Back to the mines, men. Think on that eventful day in July when Dewey went into Manila Bay, never giving a tinker’s dam for all the mines concealed therein. Come on, play ball.

The best version of what happened next (one of several he told) came from Arlie Latham, who said that Corcoran began pulling up the wire at a run, coiling it around his arm and following it back all the way to the Phillies’ outfield clubhouse, where he threw open the door and found Morgan Murphy, a pair of expensive binoculars, and a telegraph tapper.

“What cher doin’?” Corcoran is reported to have asked.

“Watching the game,” Murphy replied, an answer that was as truthful as it was incomplete.

The interaction, if it happened at all, could have gone any number of unpleasant ways from there, but luckily for Murphy he was merely required to return to the Phillies’ bench. The Reds didn’t even bother to take his binoculars.

The sign-stealing telegraph, soon dubbed “Murphy’s Signal Service,” had been shut down, but the Reds’ own pitcher was so wild they ended up losing anyway.

Players usually warmed up on the field before a game, but early the next day Tommy Corcoran was out there with a broomstick, digging for more buzzers.

Once the game started Pearce Chiles surprised everyone by coaching from the first base lines, where he stuck to one particular spot and again showed a serious case of the jimmy leg.

Corcoran and several other Reds converged on the spot during the third inning, digging frantically and unearthing a large board, which they carried back to their bench like a captured Enigma machine. It turned out to be just a board—one which Chiles had buried there long before the Reds arrived. Everyone present had a good laugh, but national outrage over the Signal Service was spreading.

One editorial condemned the scheme as “one of the most despicable artifices ever used by a team of baseball players to gain an advantage over their opponents.”

“The honest Quakers stand unmasked before the whole sporting world,” an influential columnist wrote. The affair showed the moral rot within the game, and many commentators felt it was evidence that professional baseball was on its last legs.

F.A. Abell, owner of the Brooklyn team, equated the Phillies’ actions to “playing with marked cards” and tried to have the whole team’s batting records for 1900 stricken from the record. Abell’s attitude was not improved when the Phillies visited Brooklyn less than a week later and members of the Superbas spotted Morgan Murphy (with his trusty binoculars) peering out a fourth-floor window across the street from the park during a game.

The Reds, for their part, traveled on to Pittsburgh and, incredibly, uncovered another mechanically assisted sign stealing operation there. While no telegraphy was involved, the Reds found a secret room in the outfield where someone affiliated with the Pirates would sit and convey the stolen signs by moving an iron rod made to look like part of a clock.

The Pirates apparently insisted that the Reds were behind the room and the signal device. Nobody believed this, but another rumor, quite plausible, held that Pittsburgh had begun their operation after acquiring a player, Duff Cooley, from the Philadelphia Phillies. In addition to gaining Cooley’s services at first base, he also clued the Pirates in on the details of Murphy’s Signal Service, inspiring them to similar creativity.

The sign-stealing operations in Pennsylvania consumed all the oxygen in the sport, one Philadelphia writer lamented.

Cranks throughout the circuit are wondering what kind of sly tricks were played on their idols, and many a star pitcher is looking over his [stats] to see when and where he got the hardest bumps. Instead of pennants and postseason games the league moguls hint darkly at wholesale investigations.

Despite the dark hints, no one affiliated with either the Phillies or the Pirates was ever disciplined for the sign-stealing operations they ran in 1900. Part of the problem was that the rules didn’t exactly speak to these situations—the league fathers had never anticipated that players would conspire to run telegraph lines under their turf. Plus, disciplinary resources were stretched thin that fall; nearly every other game in New York seemed to end in the pummeling of an umpire3.

When Mark Twain described baseball in this period as “the outward and visible expression of the drive and push and rush and struggle of the raging, tearing, booming nineteenth century,” he was not entirely giving a compliment.

When the Signal Service was discovered on September 17, Col. John I. Rogers, the Phillies’ principal owner, was out of the country. He returned a few days later and claimed to have little knowledge of the situation beyond what he could glean from reporters’ shouted questions. The Phillies’ executive promised to look into the matter.

The Reds’ anonymous source had said Rogers was—at minimum—aware Murphy was stealing signs via mechanical means. Early on the catcher had approached Rogers and asked him to pay for the binoculars.

On October 2, Rogers released his findings in a four-page typed statement. Just one paragraph of the statement, near the end, addressed the “buzzer” scandal. Having spoken with the groundskeeper and Shettsline, the Phillies’ manager, Rogers declared that the device in the box…had been left there by carnival workers.

Seriously. Carnival workers.

According to Rogers, “an amusement company” had rented the park for evenings in July, and they’d strung hundreds of electric lights around the park. “A switchboard of some contrivance” had been planted in the box to control the lights on a stage and accidentally left behind. Rogers said that when the players found out about the box they turned it into “a grotesque absurdity of a joke,” pretending Chiles could use it to receive stolen signs.

Rogers did not explain why the groundskeeper had initially claimed the box was a drain cover, nor did he explain why—as a part of a joke—Tommy Corcoran had been threatened with arrest. And of course there was no mention of the Phillies’ collective offensive downturn. Before the box was discovered the team was hitting .336 at home. After the scheme was broken up they hit just .294 there the rest of the way.

Still, Rogers insisted it was all “absolutely too silly to further discuss, and I will certainly not dignify the charge by pleading ‘not guilty.’” To show he was both learned and formidable, the owner signed off with a little bit of Latin, writing: “Minimus non curat lex.” The law does not concern itself with trifles.

But this particular trifle became too large for the Colonel and the Phillies to withstand without offering up a few sacrifices. On October 9 the league published the lists of players each team planned to retain for 1901, and Morgan Murphy’s name was nowhere to be found. “The Phillies will have to train a new electrician,” one writer observed. Murphy drifted across town, appearing in nine games for the Athletics in 1901 before leaving baseball (and crime) for good.

Pearce Chiles, however, was on the Phillies’ reserve list, at least at first. This was hard to explain, as his play had fallen a long way from his rookie 1899 season and without Murphy on the other end of the wires his usefulness as a cheat was similarly diminished. But Chiles had a job, until February 1901, when he and an associate traveling across Texas via train scammed another passenger, a war veteran, out of $100. Chiles was arrested for the theft and eventually pled guilty. Sentenced to two years in Texas’ Huntsville Prison, he made an early, unauthorized exit 16 months later and returned to a life of scrub baseball and general thuggery on the fringes of America.

86 years later, a working big league manager told Thomas Boswell that baseball’s morals had hardly changed since those early years of scheming and conniving.

“We don’t play baseball,” the manager said. “We play professional baseball.”

Amateurs play games. We are paid to win games. If you’re a pro, you don’t decide whether to cheat based on if it’s “right or wrong.” You base it on whether or not you might get away with it, and what the penalty might be.

A guy who cheats at a friendly game of cards is a cheater. A pro who throws a spitball to support his family is a competitor.

Mathewson’s account of what happened in Philadelphia ends up being about 60% wrong.

In 1900, the actual Butch and Sundance were still very much alive and the target of a manhunt across the western half of the United States. Baseball is old.

Tim Hurst, the umpire who witnessed the “buzzer” reveal, was perfect for this era. He believed it was undignified to report player misconduct to the league office when you could just challenge them to a fight after the game.

I imagine there are some current players, having lived through the Angel Hernandez Era would like to resolve umpiring disputes with a post-game fistfight.

I have read all of your Substack work so far, and this is easily among the best. Turn-of-the-century baseball was really the last throes of America's Wild West mentality, huh?