The Niekro File

In 1987, Minnesota Twins pitcher Joe Niekro was suspected of "defacing" the baseball, but the cover-up was worse than the crime.

Here on Project 3.18 we occasionally like to feature a noteworthy baseball ejection, and we’re proud to have played some pretty deep cuts in this space.

But we also appreciate that the greatest hits are the greatest for good reason, and we enjoy them as much as anyone.

Consider today’s story the “Free Bird” of 1980s ejections.

1987 marked Joe Niekro’s 20th year in major league baseball. Despite all that service time, the righthanded pitcher’s trophy case was lightly used, containing a single All-Star appearance, in 1979, and a few runner-up Cy Young votes from that same year. It was a fitting display for a pitcher who modern analytics tells us made his teams appreciably worse in 14 of his 19 prior seasons.

But why would he stop pitching when teams kept offering to pay him? Despite an overall down decade between 1972 and 1981 (a decade in which he was nonetheless continuously employed) a near-miraculous 1982 season with Houston at age 37 seems to have punched Niekro’s ticket for a further five years of decidedly mixed results.

It helped that Niekro was a knuckleballer, throwing a pitch that didn’t require a young man’s arm and paired nicely with an older man’s self-deprecating sense of humor. In early 1987 he was 42 years young and pitching passably well for the New York Yankees, going 3-4 with a 3.55 ERA in eight starts. The Yankees traded him to the all-in Minnesota Twins on June 6.

Niekro performed well in his first two starts for Minnesota, earning two wins. But on June 17 the team brawled with the Milwaukee Brewers and he got dropped trying to break it up, landing badly on his shoulder. As one of the more durable players in a durable age, Niekro missed just one game, but eight starts later he was 0-4 with a 6.28 ERA. His knuckler wasn’t dancing post-injury, and if Niekro didn’t have his good knuckler, well, he didn’t have much.

The Twins were leading the American League West on August 3 and playing the California Angels in Anaheim. Niekro took the ball yet again, but the first few innings were a struggle, and he allowed four hits and issued four walks. Two runs came across, but he escaped disaster by stranding six runners using pitches so baffling that even his catcher, Sal Butera, struggled to track them down.

That’s when the muttering started.

Umpire Tim Tschida was working behind home plate, and the Angel hitters complained that there was something wrong with Niekro’s pitches, some of which were behaving…atypically, even coming from a knuckleballer.

Tschida began an investigation, and he soon found two balls that showed noticeable scuffing, right over the printed signature of American League president Bobby Brown. In between innings he consulted with Dave Phillips, the umpire crew chief, who took charge.

Put them back in your pocket and make sure you know where they are. I’ll check some balls at the end of the inning and get the other guys to be on the lookout as well.

The officials were trying to keep things quiet, but the collection of practiced eyes in a major league dugout rarely miss anything happening on the field, and Angels manager Gene Mauch knew a sting when he saw one. “I noticed an umpire pocket a ball and I thought, ‘They must know something.’”

Phillips’ own checks revealed two more defaced balls. “I told Tim that if there was another pitch that he thought was illegal, we were going to the mound to check Joe out. I told him just to nod to me and I would be right there with him.”

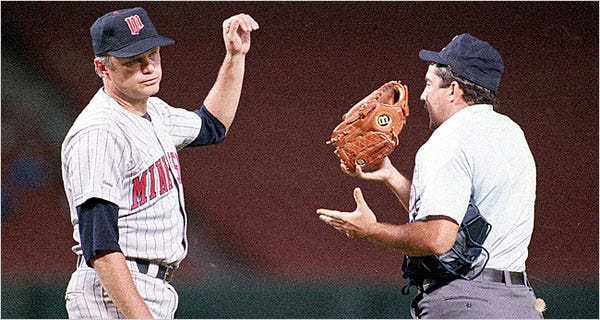

Joe Niekro threw such a pitch in the fourth inning. With a 1-1 count on the Angels’ Brian Downing, he threw a ball that moved so unnaturally that Tschida didn’t even need to give the prearranged signal. He and Phillips both broke for the mound and Tschida called for Niekro to throw him the ball. Strangely—for a man who’d spent part of three decades throwing a ball at a much smaller target—Niekro’s lob to the umpire was five feet off, landing in the dirt. Tschida brushed off the obscuring dirt and confirmed that poor Dr. Brown’s signature had been defaced again. He marched to the mound, trailed closely by Butera, the catcher.

Seeing umpires converging, Niekro turned his back on them and, according to Tschida, made a move for his rear pants pockets. This furtiveness sealed his fate. “We went out with the intention of warning him,” Phillips said. Instead, they’d cornered him.

“Tschida said, I want to check your glove,” Niekro said. “I said, ‘Why?’ and he just repeated, ‘I want to check your glove. I had nothing to hide, so I let him check it.” But not without a little drama, lobbing his glove to Tschida with more accuracy than he had the ball.

Tom Kelly, the Twins’ manager, arrived on the mound. Niekro was calm, but Kelly nonetheless thrust himself between the pitcher and the umpires, trying to get their attention with demands for an explanation. They ignored him, keeping their eyes on Niekro.

As the glove was checked, Phillips explained. “We’ve got several balls that are scuffed in the same spot and we noticed that you keep going to your back pocket.”

The umpires had now formed a semi-circle in front of Niekro, and Butera sidled up behind him. No one but the television cameras noticed one of Butera’s hands make a tentative move toward Niekro’s left pants pocket, but the catcher seems to have had second thoughts before he went digging.

Now Phillips asked to see what was in Niekro’s pockets. Without hesitation, Niekro produced a picture of his son, Lance. “I always carry this when I pitch,” Niekro said. “Is this what you were looking for?” Phillips said the pitcher had “a little grin” on his face.

The critical moment had arrived, but no one really knew how far the umpires could take an investigation like this.

Could Niekro refuse a search? Probably. What would happen if he did? He’d still be ejected, but with grounds to make a later protest. “It all happened pretty quickly,” he said later. He decided to attempt one last bit of sleight-of-hand.

Niekro put his hands deep into his pockets and pulled them out, drawing his arms up. As he did so, he flicked something out of his right hand, and it fell to the ground a few feet away. Several of the umpires missed it, but one, Steve Palermo, happened to be looking in just the right direction to see it land. As he went for it, Niekro did, too, acting as if he’d dropped it by accident.

It was an emery board.

“What’s this?” Phillips asked.

“Oh, I use that to file my nails between innings.”

“I didn’t believe him for a minute,” the umpire wrote in his autobiography, “and it didn’t really matter because it was illegal to carry that while pitching.” The umpires also recovered—though it is unclear from where, exactly—a small patch of rough-grain sandpaper.

Baseball’s most famous stop-and-frisk. Watch it once for the fun, and then watch it again and pay very close attention to Niekro’s left hand at 1:05. Remember, a good magician always wants you looking somewhere else.

Catching a pitcher cheating was like finding a leprechaun. In 1987 alone, officials had made dozens of ball checks, hat checks, glove checks, and hand checks without finding anything. Opposing players howled, managers complained, and the umpires made cursory and awkward inspections while the accused grinned or feigned annoyance. When these one-act plays ended, the shenanigans quickly resumed.

But now that a pitcher was dangling on the hook, the rulebook was ready for him, courtesy of Rule 3.02, affectionately known as Gaylord’s Rule, which had dramatically widened the definition of baseball tampering to reflect the sophistication of the modern scoundrel:

No player shall intentionally discolor or damage a ball by rubbing it with soil, resin, paraffin, licorice, sandpaper, emery paper, or any other foreign substance.

Here the umpires had damaged balls and a foreign substance—a beauty tool. Open and shut. Phillips pointed Niekro in the direction of the Twins’ dugout. The pitcher tried looking dumbstruck, but he wasn’t a good enough actor to attempt outrage in these circumstances. He and Kelly, the manager, continued to protest for several minutes as the umpires, in front of the cheering crowd of 33,000 people, loaded a half-dozen baseballs into a clear plastic bag, a body of evidence that would be sent to American League headquarters.

“Niekro did a pretty good job on a couple of those balls,” Gene Mauch said. “They were hurting.” The Angels manager had never personally complained, and with excellent reason. His own pitching staff included Don Sutton, widely regarded as one of the great abrasion artists of his time. Lest the umpires think him a hypocrite, Mauch knew he had to sit this one out.

But the manager did offer what was a commonly held sentiment in the American League at that time. “Nobody ever suspected Joe Niekro of scuffing the ball,” Mauch said. “Everybody always knew it.”

And he was far from the only offender.

If you were willing to keep them anonymous, they were happy to talk.

“You can scuff the ball anywhere you want,” one pitcher explained to a New York Times reporter. “You don’t have to have a great big cut to make it do something. What you do when you throw it is you turn the scuffed part the opposite way of the way you want the ball to go.”

Cheating was a blend of skullduggery and a remarkable amount of improvised science. Even if they’d never taken a single physics class, major league pitchers were self-taught experts in spheroid aerodynamics.

“The scuff mark, as it’s passing through the air, creates a drag,” pitcher Jerry Koosman said. “And that drag, being on one side or the other, makes the ball break a certain way. If you put a scuffed ball in a wind tunnel, hanging on a string in simulated conditions, you could see it.”

The anonymous pitcher was happy to share some of the fraternity’s tricks. A little too happy, even:

With the sandpaper, you cut pieces about one inch by one inch and glue a piece on the inside of your glove hand. That way, when you rub up the ball, you can scuff it with the sandpaper. You can change it every inning if you want or you can leave it on for three or four innings. You always leave one tip unglued so if the umpire comes out you can flip it onto the ground or in your back pocket or in your uniform.

This was remarkably close to what had played out with Niekro. Phillips said the sandpaper they found on him was “contoured to fit a finger.”

“I’m sure he had it stuck to a finger on his glove hand. When we examined the sandpaper there was a fingerprint on the back side.”

There were other ways to scuff, the anonymous pitcher explained. A pitcher could bend back the eyelets on his glove and use the protruding metal, or another player could scuff the ball on the dirt or even the rough cinders of an outfield warning track.

Sometimes the umpires really weren’t looking. Some of them hated how Gaylord’s Rule reimagined them as amateur sleuths and forensic techs. Why did they have to do more work because certain pitchers were good at what was essentially tradecraft?

“It’s been going on for years and years,” one official said. “It’s not my responsibility to look for scuffed balls and corked bats. You have to point it out to me. My job is not to search and seize.”

As Joe Niekro’s replacement, Dan Schatzeder, warmed up, Phillips gave the bag of tainted balls to one of the Angels’ batboys and told him to put it in his locker in the umpires’ dressing room.

Under the stadium, the batboy, 17-year-old Jeff Parker, was confronted by Al Newman, one of the Twins’ bench players. According to Parker, Newman stopped him and made a grab for the evidence.

“I’m surprised the bag didn’t rip,” Parker said. “He had a hold of two of the balls through the bag. He leaned over me, trying to get the balls, and forced me to my knees. I buried the balls in my chest and bent over so he wouldn’t get them1. He roughed me up trying to get the balls, and I ended up on the ground.”

Newman initially declined comment, but when told the batboy was going public, he thought of one. “I’m not denying seeing him,” Newman said. “I’m not denying asking him to let me look at the balls. But I sure deny wrestling that kid to the ground. I asked if I could see the balls and he said no. After that, I left him alone. He’s a 100-pound kid. I’m going to try to bury him, right?”

One way or another, the balls ended up in the umpires’ room, back within the chain of custody and ready to be boxed up for their overnight trip back to New York.

It is a little unfair to compare anyone to Gaylord Perry, a man so brazen that he wrote a mid-career speculative tell-all book called Me and the Spitter while insisting that all that stuff was behind him. Perry’s doublespeak was even better than his “forkball.” Slow-poured in a Southern drawl as thick as motor oil and chased with a fox’s grin, his winking declarations of innocence made him one of the sport’s great anti-heroes and sent opposing batters into psychological crisis.

The general of principle the Perry Method was to confess while admitting nothing, and this was not an easy line for mere mortals to walk. After he was caught red-handed, Joe Niekro gave it his best shot, but Gaylord he wasn’t.

“I’ll be honest with you,” Niekro told reporters. Not a great start. Has anyone ever prefaced a truthful answer this way? “I’ll be honest with you,” is just icing for a lie. But we digress. Please, Joe, go on.

“I always carry two things out there with me,” he said. “An emery board and a small piece of sandpaper.” This was a knuckleball thing, he explained. In order to properly throw a knuckler, the ball had to be gripped with the fingernail edges, and rounded edges didn’t work. Knuckleballers had to keep their nails trimmed perfectly straight and flat to get a proper grip on the ball. “I file my fingernails between innings,” Niekro said. “And if I need to, I’ll even do it between pitches, which is why I carry it with me. I’ve been doing it for 15 years.”

There was no question that the emery board was a necessary tool of the knuckleman’s trade, and others in that brotherhood publicly came to Niekro’s defense.

Charlie Hough of the Texas Rangers said he too carried an emery board with him all the time. “I carry it in my cap, not in my pocket where it might get wet.” Hough also insisted you couldn’t cut a ball with an emery board, and then he produced a ball and a board and tried to do it, without success. “See? It doesn’t do anything to a ball at all.”

The sandpaper was harder to explain, but Niekro tried—twice in as many sentences.

“Sometimes I sweat a lot, and the emery board gets wet and I can’t use it. That’s why I have the sandpaper.” Oh, and: “And I’ll also use the sandpaper on small blisters.” Wonderfully versatile stuff, sandpaper.

For at least one pitcher, that was where the story started breaking down: “Sandpaper is a little fishy. What are you going to do with an emery board—take it out and file the ball? With sandpaper, maybe you could hide it in the palm of your hand. Sandpaper…that’s a legitimate beef there.”

“If I’m guilty, I’ve been guilty for 15 years,” Niekro insisted, and he demonstrated his consistency on the night after his ejection, when cameras found him in the dugout, taking care of business.

After Dr. Bobby Brown “personally” inspected each of the balls (Gene Mauch had characterized them as “borderline mutilated”), he affirmed the automatic 10-day suspension as outlined in Rule 3.02. Niekro appealed, with help from his manager and general manager, but the appeal went to…Dr. Bobby Brown. The appellate magistrate unsurprisingly upheld the lower court’s earlier decision.

His on-air frisk-and-flick became a signature of sports blooper reels for years afterward, but umpire Dave Phillips didn’t think Niekro’s heart was as full of larceny as some of his peers.

“Joe was kind of a unique case,” he wrote. “I don’t believe he threw illegal pitches throughout his whole career. He actually had some fun with the suspension and the publicity. He really had no defense, so it was a credit to him that he had fun with it.”

If he was anything, Joe Niekro was a survivor, someone who’d outlasted many far more gifted athletes by virtue of superior guts and inconsistent guile. The emery board incident had no impact on his Cooperstown chances, which were already nil. And while the situation was embarrassing, it was nonetheless an opportunity.

“I signed my first two emery boards the other night,” he said on August 5.

Maybe I should go into the emery board business. Half the people probably didn’t know what an emery board was before this. They knew what a fingernail file was but not an emery board. Heck, one of the guys on the team, and I don’t even remember which one, came up Monday night and said, “What’s an emery board?”

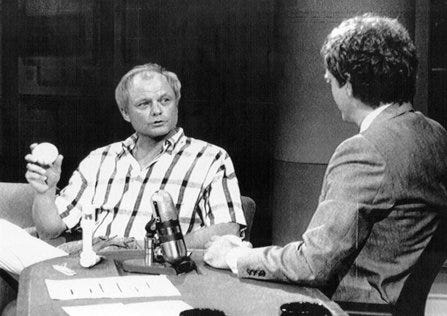

Niekro used his mandatory unpaid vacation to make a visit to Late Night with David Letterman. Letterman had already interviewed Gaylord Perry in 1983 (who did not disappoint, bringing out his two pet lion cubs) and the host, something of a rogue himself, loved talking a little shop.

The pitcher showed he understood the assignment by walking out on stage wearing a carpenter’s apron bristling with an electrical sander, nail files, and even had a little sandpaper glued to the sole of his dress shoe.

Letterman took it easy, but Niekro was far from the verbal jiu jitsu artist he’d need to be if he really wanted to live a life of crime. He provided hypothetical answers on how a pitcher might alter a baseball, but with a little more stumble and stammer than a practiced cheater, a performance that left the late night host unconvinced. “So you’re telling me you did not doctor the ball that night?”

Niekro seemed caught, but at the last second the old knuckler managed to dance away:

“Dave, do I look like a doctor?”

You can’t go wrong with the classics.

Wow, Joe seemed like a shifty character. To my knowledge (and the HOF’s vetting) Phil never had any issues with doctoring a ball. I am currently reading Ball Four and there were certainly other pitchers who cheated.