Twisting the Tiger’s Tail - Part 2

On May 15, 1912, Ty Cobb attacked a spectator. Two days later, the Detroit Tigers attacked the system.

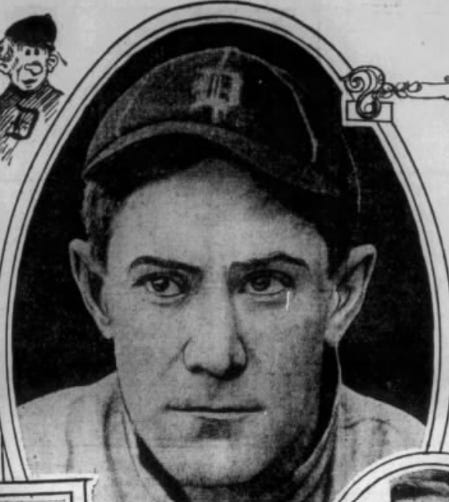

This is the second part of a 1912 story that nearly transformed major league baseball. It all started with a fight in the stands, when Ty Cobb decided to dispense a little Dixie justice to Claude Lucker, a New York rooter who had relentlessly heckled him.

Here’s Part 1:

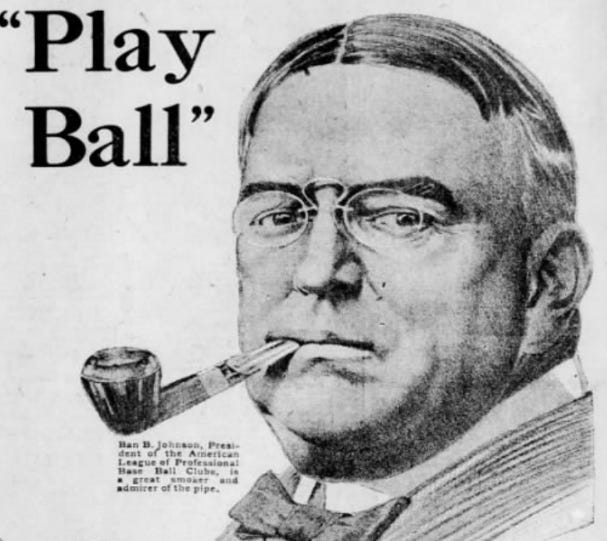

It was unquestionably bad luck for Ty Cobb that American League president Ban Johnson happened to be present to witness his one-round knockout of Claude Lucker, but the proximity did give Cobb a chance to explain himself in person before Johnson’s impression of events hardened.

According to the Detroit Free Press, Cobb did so after the game: “Cobb went to [Johnson] in the evening to apologize for the breach of discipline and laid before the executive the facts in the case.”

Some sources say that Cobb’s explanatory “...it’s time to fight,” quote, presented in Part 1, was delivered to Johnson, but this part of the story is rather foggy. Johnson was quoted on the evening of May 15, but didn’t say that he’d met with Cobb. Instead, he said this:

I don’t know until I hear the facts, but I can’t see any justification for a player climbing up in the stands and fighting a spectator. If a spectator is abusive the player has the recourse of notifying the umpires and the man can be removed.

If they did talk, it doesn’t seem like Johnson did much listening.

The umpires’ involvement is another mystery. The record clearly shows that Cobb sought help from the Highlanders’ management, but there is nothing to indicate A) whether he sought help from the umpires, Fred Westervelt or Silk O’Loughlin; and B) if he did, how they responded. That Cobb did not (apparently) appeal to the umpires became a major sticking point for Ban Johnson, and we don’t blame him.

Cobb’s supporters began rallying immediately. Even before the May 15 game ended, “prominent [New Yorkers], including several Elks,” who witnessed the affair presented themselves to Detroit manager Hughie Jennings and provided their names and addresses, offering to serve as Cobb’s witnesses, either to the police…or to Ban Johnson.

The early consensus was that the Tigers’ center fielder would likely face a fine for his actions1. “If he is fined,” the Free Press wrote, “the Detroit club probably will pay it, or else there are a lot of good, reasonable and usually peaceful citizens who saw the affair who would consider themselves honored to contribute.”

The long day was over, and the Tigers escaped New York via train, bound for their next stop, Philadelphia, where they had three games against the Athletics and one unscheduled date with destiny.

Thursday, May 16

The day began with an unexpected lull. Foul weather rained out the first game of the series, which was rescheduled deep into July. With no game to report on, there was nothing to do but talk more about the Cobb/Lucker affair and what it said about the relationship between the players and fans. The talk continued to largely favor Cobb:

Rowdyism and ungentlemanly conduct on the ball field are in no way to be condoned, but in the circumstances noted we can’t see that Cobb did anything but what any red-blooded self-respecting man would have done.

Because a man wears a player’s uniform he has to stand the insults, epithets, and worse, that anyone may choose to hurl at him.

Few players ever take a punch at a fan. The wonder of it is that more of them don’t. In no other sport could a man say to another what some fans say to ball players and get away with it—in not a few instances—get away alive.

Hughie Jennings, a well-liked manager, now found himself in an extremely tough spot (one that would get even tougher in the coming days), but he jumped right on the tightrope, voicing his opposition to violence in general but assuring reporters that Cobb “did everything possible to make the man let up on him.”

Jennings was prepared to say as much in his report to the president, but evidently Johnson already had all the info he needed. Late that night, Johnson reached out to the Detroit manager, informing him that Ty Cobb was to be suspended indefinitely.

Friday, May 17

The news of Johnson’s summary judgment roiled baseball, but few were surprised. The league president was a classic insurgent-turned-dictator who had taken the minor-league Western League and mounted a successful challenge to the National League, which had sat alone atop the baseball world until Johnson decided to make a run. Now he was the dominant power in baseball, and the man who had once disrupted baseball tolerated no disruption in his league.

“Johnson had never tolerated rowdy ball,” a New York paper wrote, “and the improvement in the conduct of players in recent years is to be credited in large measure to him. Even so conspicuous a citizen as Ty Cobb will not be allowed by Johnson to turn baseball games into ring fights.”

The loss of the league’s best player was a severe blow to the Tigers, still trying to muscle up to .500 and make a run at the defending champion Athletics. The team lacked any kind of depth in the outfield. Henry Perry, the player who replaced Cobb after the fight, had already been ticketed back to minor-league Providence and there was apparently serious talk of using one of two starting pitchers, Ed Willett or Jean Dubuc, in Cobb’s place. Even in 1912, these were dire straits, as one paper explained with most uncharacteristic bluntness:

“For a major league team to have to use pitchers in the outfield is bad.”

Most of the Tigers did not learn of Cobb’s suspension until that morning. The players were stunned and distressed. Many of them had heard the abuse Cobb suffered with their own ears. They knew that, as a star, Cobb took the lion’s share of whatever garbage fans wanted to tip onto the players.

“At times he is also the target for pop bottles,” one paper wrote of Cobb’s plight. “The lot of a baseball star is not a happy one—except on pay days.”

Seeing Johnson punish Cobb without an investigation infuriated the Tigers. They were tired of being treated like animals in a cage, enduring abuses no other professional performers had to take, and now it seemed there was no due process for American citizens in Johnson’s American League.

The club retreated into a private room at their hotel to discuss Cobb’s suspension. Jennings was not included; nor was Cobb himself.

The players devised a plan with remarkable speed. Cobb’s celebrity gave them one advantage: a platform. They resolved to climb up on it and get loud. The group drafted a public communication to their autocratic president:

B.B. Johnson, Fisher Building, Chicago:

Feeling Mr. Cobb is being done an injustice by your action in suspending him, we, the undersigned, refuse to play another game after today until such action is adjusted to our satisfaction. He was fully justified in his action, as no one could stand such personal abuse from anyone.

We want him reinstated for tomorrow’s game, May 18, or there will be no game. If players do not have protection, we must protect ourselves.

The telegram, sent around noon, was an act of defiance without precedent in either league, but especially Johnson’s. “All things hitherto have been run in perfect harmony,” one paper observed, “which at times has been a notable contrast to the manner in which the National League magnates have fought amongst themselves.”

After nearly a decade of quiet, baseball had itself a rebellion.

When the meeting broke up, representatives went to tell Jennings of their plan and others went to see Cobb. In return for their unified support, the center fielder would be a prominent spokesman on the issues that impacted all of them. Look how Cobb’s language shifts as he responds to his suspension, knowing what the players have planned:

The “I”:

There is no justice in such a decision. I was not given any opportunity to defend myself and knew nothing of any action being taken until I suddenly learned of my suspension.

No man with a right to the title would stand for the things I was called. They are unprintable, and if President Johnson would allow them to be used to him without knocking the man down who said them, he is not a man.

Becomes The “We”:

Ballplayers at present have no protection. They are absolutely subject to the whim of the president who can use his personal malice on them with no chance for appeal.

All the ballplayers in the country are tired of such conditions, and it will not last much longer. We have got to organize for our own protection. When we are organized, if a president makes an unfair decision it will be referred to our body and, if condemned, it will be ignored.

Reporters went to Jennings to ask if the players were serious. He assured them that every man was determined to stick to the bitter end:

All the players agree to stand together. This is a case where the Detroit players consider that they are called upon to stand up for the rights of a fellow member of the team.

The manager was increasingly feeling stuck in the middle between two parties that had no quarrel with him. “I wish Johnson would come to Philadelphia and straighten out this tangle.”

The Tigers were so serious they had already sketched a plan for spending the 1912 season in exile. If Johnson didn’t change course, they would begin a nationwide barnstorming tour as a team of famous renegades, capped off by a trip overseas.

“It is time the players had some rights as well as the club owners,” shortstop Donie Bush said. “We consider that we could make a lot of money by going on a road trip and touring the country. We have offers from many places and we may accept one to go to Japan.”

The Tigers left early for their May 17 game at Shibe Park. Ostensibly holding extra practice, they really wanted to have a chance to talk things over with the Athletics’ players. A series of urgent huddles and conferences were held as the Tigers made their case for collective action.

In anonymous comments made by one of the group’s ringleaders (Jim Delahanty being a strong possibility), we have some idea of what the player-to-player conversations must have been like:

It has come high time that we form an association for the protection of our rights. Nowhere are we afforded the protection we should have. At the theatres the actors all have protection that will prevent any spectator from hurling things at them or calling them names. But a ballplayer! Why, we are subject to so much abusive language at times that it is a wonder some of us haven’t been arrested for murder long ago.

Then, too, we are frequently targets for pop bottles, wads of paper, and other things. If the average fan knew some of the epithets that are hurled at us it would not surprise him that we lose our tempers. Why, I have heard players called vile names and reflections made on their mothers and sisters and other things just to rattle them. Is it any wonder if sometimes one rises in his wrath and jumps into the stand to punish such an insult?

The only way to avoid such an occasion as the Cobb incident is for the owners of the ballparks to properly police the stands. Then, if a spectator refused to stop abusing the players, dutifully eject him from the park. It has certainly come to a point where we have got to organize and protect ourselves.

“Jennings’ revolutionists” won their pre-protest game, 6-3, still short a star but braced by an outstanding pitching performance from would-be outfielder Jean Dubuc, who allowed only six hits, and few balls even reached the outfield. This may have been a relief to back-up infielder Paddy Baumann, forced to play center field in Cobb’s absence. Baumann went 1-for-5 but drove in two runs, and Dubuc’s pitching was such that Cobb’s replacement had nothing to do on defense but stand in place and look ready.

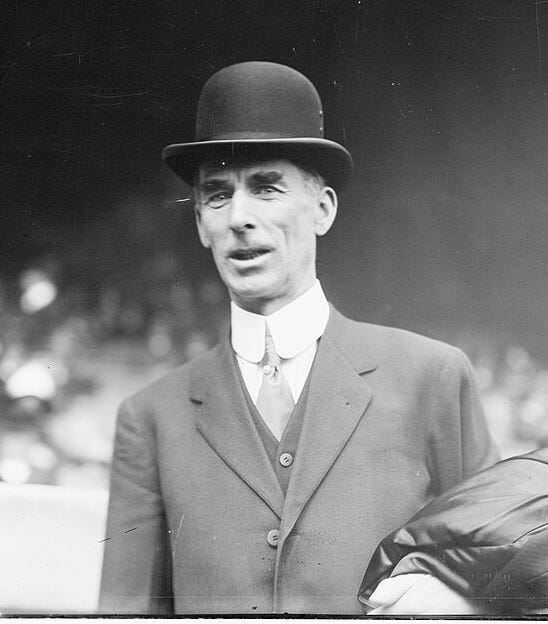

The Tigers’ organizers had been persuasive. That night, a small delegation of Athletics visited with their living-legend owner and manager, Connie Mack, informing him that if the Tigers failed to take the field on May 18, they wouldn’t either.

Hearing this, Mack reportedly smiled and said he would meet them in the morning to talk things over. He would soon deny the conversation ever happened:

I have not heard any word concerning a sympathetic strike. So far as my men are concerned I know them so well that I must hear it from their own lips before I would believe that they are contemplating such a thing.

The Tigers had also made contact with the rest of the eight American League clubs:

They are sending messages to friends urging the formation of an organization of ballplayers for self-protection. They are getting encouragement from all over the country. An effort by the AL authorities to discipline the Detroit team for insubordination might bring on a strike in both leagues.

As the telegraph wires heated up, the plan was baked. May 19 was a Sunday, which, in Pennsylvania, meant no games could be played due to those pesky Blue Laws. By a stroke of luck, all eight teams were playing in nearby cities, and the Tigers and Athletics said they would call a special assembly in Philadelphia on May 19 in which delegations from all clubs could form a representative organization “which will afford the players the same rights accorded to every other professional performer today.” The fledgling organization already had a name: the Players’ Protective Association.

If Cobb was not back in the field by Monday, May 20, the all eight teams would strike “until some consideration is given to their demands.”

The Cobb/Lucker affair had gone from local to regional to national importance in less than 48 hours and was threatening to “reach enormous proportions” if Cobb remained suspended:

There is a new baby in the cradle of liberty. Within a gunshot of the building in which our forefathers signed the famous declaration asking for waivers on George III, the Tigers today took a firm stand for that “pursuit of happiness” which is classed among the inalienable rights.

Johnson was traveling that day and did not respond to the Tigers’ ultimatum until late in the evening:

“The suspension has not been lifted and will not be until all the evidence possible relative to the affair is in my hands.”

He promised that Cobb would not play on May 18 and likely would not play for some time. And as for the striking Tigers:

“Detroit will play tomorrow or it will cost somebody a ‘snug’ sum of money.”

That “somebody” was the Tigers’ principal owner, Frank Navin.

Reached for comment on May 17, Navin promised to stay out of the dispute:

I haven’t communicated with Manager Jennings or the players and I do not intend to. I have every reason to believe that everything will turn out all right just as soon as the players learn that Mr. Yawkey (Detroit part-owner Bill Yawkey) and myself are the losers by it. We have no quarrel with the boys.

Navin’s problem was with the rules, which outlined severe punishments for clubs that failed to participate in scheduled games—punishments that were ultimately the responsibility of the club owner. If the Tigers refused to play on May 18, Navin explained, that would be a forfeit under the American League constitution, meaning a loss for Detroit, an easy victory for Philadelphia, and a $5,0002 per-game fine for Navin personally.

But the fines would only get so high. If a team demonstrated it couldn’t be relied upon to show up and play, the league could could claw back the franchise and ship it elsewhere.

Publicly, the owner was eager to back the Tigers:

I want it stated plainly that I am in full sympathy of the players in supporting one whom they apparently are justified in believing was harshly dealt with. … I have no fears that the boys soon will see the proper course to pursue and straighten the matter out to the satisfaction of all. Two wrongs never made a right. However, I will leave it to the boys themselves. They can act as they see fit, but I am sure it will be the right way.

But privately, Navin telephoned Hughie Jennings and explained the stakes: thousands of dollars a day in fines and the possible loss of the club. The strike was an existential threat to the Tigers, he warned the manager, and he was coming to Philadelphia to intervene. Until then, Jennings had to handle things. The most pressing concern was the game on May 18.

“Put a team on the field,” Navin told him. Any team. “Even if it costs $10,000.”

It would end up costing much less than that.

Next Tuesday we’ll have the story of May 18, 1912, when a farce worthy of Mel Brooks’ Bialystock and Bloom entered into baseball’s actual record books. In it, the Athletics’ famed “$100,000 infield” squares off against Jennings’ “$400 Tigers.”

Next:

If this had happened in 2025, you can imagine heavy prop betting on Cobb’s eventual punishment.

$5,000 in 1912 is about $162,000 today.

So this is how Marvin Miller got his start. . .

The reference to “The Producers” made me think of Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick! Can’t wait for next week, Paul!