The Tigers Off The Street

The story of a historically absurd loss is also kind of a fairy tale.

On May 18, 1912, the Detroit Tigers fielded a team of replacements against the world-champion Philadelphia Athletics. The team’s actual players had called an unprecedented strike to protest what they felt was the league’s unjust treatment of their star, Ty Cobb, who had received an indefinite suspension for assaulting a mouthy spectator in New York a few days earlier.

Without players, Detroit faced a forfeit and a hefty $5,000 fine. To avoid these, the Tigers’ owner ordered the manager, Hughie Jennings, to put a team—any team—in the field.

We’ve written this as a standalone feature, but if you’re interested in the saga that led up to this moment, go ahead and start here:

On the morning of May 18, 1912, Hughie Jennings met privately with his players at their hotel in Philadelphia. He emerged looking glum.

“The men are determined,” Jennings told the circling reporters. “They will not play, I am sure of that.” The manager had no choice but to move to Plan B. “In order to protect the franchise I am scouting around all over the world for players to place a team in the field.”

Asked how he would conduct a global search in less than three hours, Jennings said he didn’t know, but he was checking in New Jersey.

As precious minutes ticked by and New Jersey failed to give up its riches, Jennings asked the Athletics’ manager and part-owner, Connie Mack, where the Tigers might find some good players right there in Philadelphia. Mack had a suggestion.

Before the 1912 season opened, the Athletics played an exhibition game against the varsity baseball team from nearby St. Joseph’s College. Philadelphia took it easy, mostly playing their reserves, but the St. Joseph’s team played their starters and went hard. In a moment they’d never forget, the college boys came away with an 8-7 victory.

The game surely left some impression on Mack, and when Hughie Jennings came looking for help, Mack put him in touch with a father/son duo ideally situated to make a connection at St. Joseph’s. William Nolan was the sports editor for the Philadelphia Record, and his son, Joe, was a sports reporter for the paper and a St. Joseph’s alum. Joe Nolan was friendly with the team’s non-playing assistant manager, a junior named Aloysius “Al” Travers, who supplied statistics and game records for the local newsmen. On May 18 Nolan came knocking on Al Travers’ door asking for something different.

“John came to my home about lunch time on the day the strike,” Travers recalled. Travers, then 20 years old, was living with his parents. Nolan explained the situation and presumably asked Travers to see if the varsity players could help out, but the St. Joseph’s team had played the day before against Conway Hall and were in transit and unavailable.

Elsewhere, Hughie Jennings got a lead on a respectable group of players from Pennsylvania University. These collegiates were available and interested, but their manager, Roy Thomas, forbade it. Thomas was a recently retired big leaguer, and he kept his players home in solidarity with the real Tigers. Time was running out and Jennings was said to be looking like a person “on the verge of a nervous breakdown.”

Meanwhile, Nolan and Al Travers had kept thinking. Travers could play a little—and he was well connected in the area.

“Nolan told me to get some 10 to 12 fellows from around the neighborhood,” Travers said. “I was surprised, also happy, at the chance to get into the park to see the game, so I hurried down to 23rd St. and picked up the boys.”

The various parties agreed that anyone who suited up for Detroit would earn $10 for doing so. It wasn’t Plan A, B, or C, but at least Plan D would be cheap.

Given their participation in this latter-day fairy tale, there has been particular historical interest in ascertaining the “boys’” identities—no easy task, as we’ll see. For a full report on their collective biographies, we happily point you to this excellent account from SABR researcher Kevin Barwin, but here we will limit ourselves to some of the highlights.

Al Travers was the captain of the team and the day’s only pitcher. Some outlets assumed, understandably, that the St. Joseph’s man was a “star pitcher” from that school, but not only was Travers not a star or a pitcher or even a player on his club, he had never pitched before.

“Mr. Nolan, Manager Jennings, and I made out the batting order,” Travers explained. “I placed myself in right field and batted forth. Mr. Nolan wanted to know why I was down for right field. ‘Whoever is going to pitch gets the most money,’ he said. So I changed the lineup and took the pitching assignment.”

Also among Travers’ Irregulars:

Second base: Jim McGarr, 23, a machinist in a locomotive factory.

Shortstop: Patrick Meaney, 40, a long-time minor leaguer and semi-pro player who lived just a few houses from teammate McGarr. One of these two probably recruited the other.

Left field: Daniel McGarvey, 24, a chauffeur.

Center field: William Leinhauser, 18, an auto machinist and possibly an amateur boxer. Due to typeset limitations (and, we must say, in keeping with the overall spirit of things) one indifferent paper listed Leinhauser as “L’n’h’s’r,” an attribution that one writer later worried would cost the player his rightful claim to fame1: “Today nobody knows whether his name was Loopenhouser or Lagenhassinger, and I bet his own wife calls him a liar when he says he played for the Detroits.”

Right field: Joseph Ward, 26, worked as a salesman and was apparently a “well-known sandlot player in the New Jersey and Philadelphia area.” New Jersey came through!

Utility: John Coffey a.k.a. Jack Smith, 18, the youngest of the group. To make future historians work as hard as possible, young John played under an alias. And with good reason—he may have been an escaped convict. In March 1912, Coffey had been arrested for larceny and receiving stolen goods and sentenced to three years at the Pennsylvania Industrial Reformatory. And yet, here he was, two months into that sentence, a member of the Detroit Tigers.

Utility: William Irwin, 34, a journeyman minor league player and one-time bullpen catcher for the Phillies. That the experienced Irwin did not make the starting lineup is one of many things about this day that makes no sense.

Third base: Billy Maharg, 31, a farmhand and auto mechanic. Maharg was a professional featherweight boxer and a shadowy character. Rumors later spread that “Maharg” might be a nom de guerre, being the perfect inverse of “Graham,” but this was false.

Travesties followed Billy Maharg like a cloud of flies. He would later become the Phillies’ assistant trainer (something of a gofer and driver), and in 1916, on the last day of the season, he was inserted in another major league game, pinch hitting in the eighth inning. He grounded out and played right field in the ninth.

Maharg later played a meaningful role in the conspiracy to bribe disaffected members of the Chicago White Sox to fix the 1919 World Series. He later testified to his involvement, receiving both immunity, and, posthumously, a cinematic portrayal, in 1988’s Eight Men Out.

But we’re still not done with Maharg, because, according to one source, he had a nickname: Doddles.

And thus ends the long search for the ultimate weird old-timey baseball name. Our clear winner is Billy “Doddles2” Maharg.

The Tigers supplemented their recruits with two veterans, or as one paper described them, “comebacks from Noah’s League,” so grizzled and leathery “they can sleep in a swamp without mosquito netting.” Both were members of Hughie Jennings’ coaching staff and part-time scouts for the team.

Just as in little league, one of these trusted hands was stashed at first base. Joe Sugden—gone prematurely gray at age 41—played for five major league teams between 1893 and 1905. Sugden’s years as a catcher in an age of thin gloves and no leg protection had wreaked havoc on his body. ”It was said that shaking his gnarled paw was like grabbing a handful of hickory nuts,” but Sugden had kept in shape and even played first base a few times in preseason exhibition games that spring.

The other veteran was Jim “Deacon” McGuire. 48 years old, McGuire had been a major league catcher for 26 seasons between 1883 and 1910, playing for 12 different teams and doing three different stints as a manager. He played alongside Hughie Jennings in Brooklyn in 1899 and 1900 and joined Jennings’ staff in 1912. Despite being the oldest of the team’s three catchers, McGuire got the start behind the plate.

Once the theoretical lineup was made, Jennings told Travers to take his club out to sit in the stands and wait.

Though committed to their protest, the real Tigers agreed to help Jennings by buying him time to find replacements. They would go to the park, dress, and warm up, awaiting any last-minute reprieve for Cobb, however unlikely. This tactic would keep the Athletics from getting opportunistic and trying for an early forfeit in the absence of uniformed competition.

It was a warm spring day and news of the Tigers’ strike threat was everywhere, turning the game into a local event. 20,000-some people came out, many of them early, to see if the players would follow through.

The suspended Ty Cobb was white-faced and determined:

I play with the most loyal team in the world. These fellows will stick. I know that [the league] will not let me play today and this means that 18 men will walk away from the grounds. You can bet your soul on that.

The exiled star was allowed to practice with his teammates, but when his name appeared on Detroit’s lineup card, the umpires told the Tigers Cobb had to go. Hearing this, second baseman Jim Delahanty, the striking players’ ringleader, gave the signal.

In the pitcher’s box the man who was twirling threw down the ball and started from the field. Cobb was practicing with the rest. He tossed the ball on the pile at the bench and gathered with the players in a group around Jennings.

Eighteen men walked off and the strike was on.

There were rumors that the Athletics might join the walkout, but Connie Mack had smothered any sparks of solidarity, reminding his players that they were chasing an upstart Boston team. A forfeit was a sure win, and if Jennings managed to cobble together a pseudo-team, well, the Athletics could grab an easy victory and pad out their batting averages—if they played.

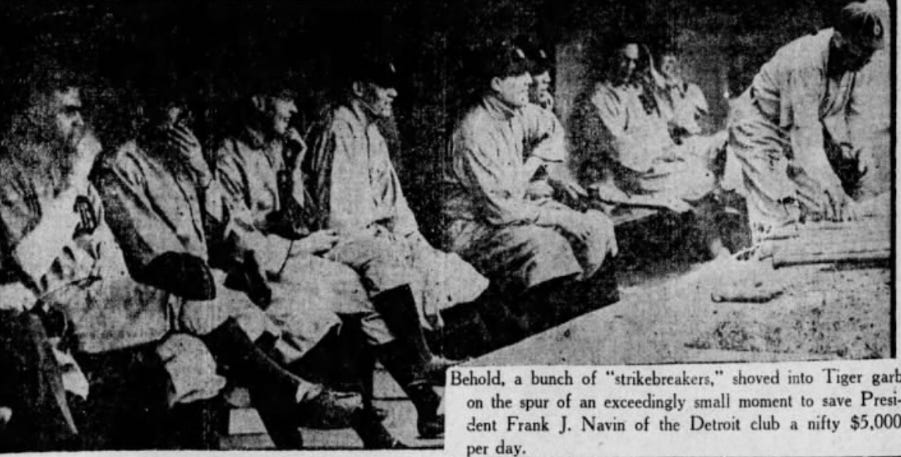

As the Tigers filed back into the visitors’ dressing room, Jennings motioned for Travers and his crew to leave their seats in the bleachers. To those not briefed on Plan D, it looked like the Detroit manager was plucking new players right out of the seats:

Through the stands was carried the rumor that Jennings wanted amateurs. By the dozens, amateurs, semi-professionals, and college athletes left their seats and swarmed around the Detroit bench trying to look like real players.

Nolan, the sports editor who’d helped Jennings find a team, ushered Travers and the others into the dressing room, where Tigers old and new briefly met.

It was a fraught, potentially combustible moment. Travers and the others were strikebreakers, and here they were in close quarters with the men whose strike they were breaking. But Jennings trusted his players and had dealt fairly with them. They were magnanimous in return, handing over their grey road uniforms, still warm and damp with sweat, to the new men. Of what must have been a feast of engrossing interactions, only a few tantalizing scraps have come down to us today.

“As quickly as they discarded their suits, we put them on,” Travers remembered. “I put on [pitcher] George Mullin’s suit.”

“Listen, kid,” Mullin said, “you can steal anything you want but don’t pinch the glove.” Elsewhere, other Tigers were graciously leaving their own gloves and shoes behind for the replacements to borrow.

The tension might have been eased by the fact that even as the replacements suited up, few on the Detroit side thought they would ever see the inside of a box score.

“We never thought we’d play a game,” Travers said. Connie Mack, directly or via Nolan, had assured Travers that he and his squad were only to “make an appearance on the field.” An appearance would technically prevent the umpires from calling a forfeit, and then, Mack claimed, the teams would postpone the game. For his part, the Athletics’ part-owner apparently didn’t expect 20,000 people to show up, but once they did, he changed his mind about postponing.

“Connie Mack, seeing a good crowd and anxious for an extra dollar, double-crossed [us],” Travers remembered. “The game wasn’t called off. We didn’t mind, but I never thought too much of Mack after that.”

“We were nothing but a bunch of nondescripts,” Travers said. “It’s a wonder we got anybody out.” On this day wonders would abound.

The Athletics were a dynasty of the time, winning back-to-back World Series in 1910 and 1911. Their infield remains one of the best ever, featuring Hall-of-Famers Frank Baker at third and Eddie Collins at second, Jack Barry at shortstop, and Stuffy McInnis at first. Each of these men had played their way into (for the time) big salaries that added up to baseball’s first “$100,000 infield.” The Athletics had speed, outstanding contact skills, and even (in “Home Run” Baker) shadows of the long-ball power that would soon reshape the sport.

Connie Mack would shrewdly use the occasion to rest his pitchers, giving three different men three innings apiece, but aside from that and a few bench players in the outfield, the Athletics held nothing back.

After a preliminary 1-2-3 attempt at offense, Travers tried his hand at pitching.

“I had a beautiful slow ball,” Travers self-reported. “The Athletics couldn’t get used to it and were just hitting easy fly balls. The trouble was, though, that no one was catching them. The outfielders would let the ball bounce before picking it up.”

With two on and none out in the first, Travers faced Home Run Baker and counterintuitively decided that was the moment to try a fastball.

I put everything I had behind the pitch. He put the ball over the right field fence–fouled by a couple of inches. Jim McGuire walked out to me. “Son, if you value your life, no more of them fast balls—keep feeding ‘em that slow stuff. It isn’t good enough to hit.”

The Athletics scored three runs in the first and three in the third, but none in the second and the fourth, achievements made even more remarkable by the fact that defensive errors required Travers to get four outs in both scoreless frames. Travers even got a strikeout later on, against one of the Athletics’ pitchers.

There were other highlights. In the second, left fielder Ward made a leaping catch of a smash into deep right-center. “When he got back to earth and found the ball sticking in his glove,” a Philadelphia reporter wrote, “we’re willing to bet he was the most surprised young man in the wide, wide world.”

Early on, the Philadelphia crowd had booed and hooted at the “Tigers’” poor play, but perhaps the fans began to imagine themselves in Joe Ward’s place, beginning the day on a stoop somewhere and now looking down to find a major league out nestled in Wahoo Sam Crawford’s donated glove. There were increasing cheers for the visitors—and some of those came from the striking players themselves.

Back in civilian clothes, the players had made a show of getting into their cabs, presumably heading back to their hotel, but the cars circled around and let them off in front of Shibe Park, where they bought tickets and dispersed into the stands.

“Yes, the boys are all here,” second baseman Jim Delahanty said, “but they are scattered around. This is great. I wouldn’t have missed it for anything.”

At the end of the third inning a man—evidently not enjoying the overpowering novelty of the situation—rose from his seat and shouted, “Let’s go get our money back!” Several hundred bleacherites rushed for the ticket windows, but Mack’s operation was unsympathetic—the fans had been promised an official major league game, and such a game was in progress back the way they’d come. Most of the malcontents slunk back to their seats and the crowd jeered them more harshly than they did the Tigers.

Meanwhile, other paying customers seemed to be having a fine time. “It’s a circus,” Detroit shortstop Donie Bush said from his grandstand seat. “I’m glad I came back.”

Years later, Travers could still recall poor Billy Maharg’s struggles. “My third baseman was afraid of getting hit, and played in short left field.” The Athletics, naturally, exploited this by bunting base hits down the left field line.

With two outs in the third, Doddles’ worst fears came true when a hot grounder jumped up and caught him flush in the mouth, reportedly dislodging several teeth. Somehow Maharg managed to recover in time to retrieve the ball and successfully throw out the runner and end the inning.

Maharg was removed—probably at his own request—and replaced by the experienced Bill Irwin, the only conscript who had any success at the plate, going 2-for-3 with two (wasted) triples. He also switched over to catcher in the seventh when McGuire’s 48-year-old legs started to give out.

Before they returned to retirement, Sugden and McGuire hit back-to-back singles in the fifth inning and both men scored on a wild pickoff throw that may have been the Athletics’ way of tipping their cap to their elders. When that inning ended, the score was a competitive 6-2.

“Then,” Travers said, “came the revolution.”

Perhaps the Athletics realized how it would reflect on them if these Tigers ended up making anything like a game of things. Beating a bunch of nobodies by just four runs would have been an utter embarrassment for the reigning champs, and in the bottom of the fifth they opened the throttle wide. “They all bunted me crazy,” Travers said. “They must have made 15 bunts.”

Eleven Athletics went to the plate that inning, and the parade only ended after a batter, Danny Murphy, tried to stretch a triple into an inside-the-park home run and got thrown out by 18-year-old “L’n’h’s’r,” the abbreviated auto machinist.

That was as good as things got for young Leinhauser. He did get one hit, though—a fly ball missed his glove and grazed his head, raising a bump under Ty Cobb’s hat.

From that fifth inning onward the Detroit outfielders were quite miserable, so much so that “it became necessary for Jennings to relieve his men at frequent intervals to prevent their dying of exhaustion.”

“I was chasing hits all over the outfield,” Leinhauser said. “Jennings finally came out and told me to forget about trying to catch them. ‘Just let the ball go and play it off the wall.’”

By the top of the ninth inning the score was 24-2. Connie Mack’s “White Elephants” had “kept the dust around home plate stirred so much that nobody could really see what was going on,” fattening their batting averages and extinguishing any threat to their dignity.

Now Hughie Jennings played his last card. Apparently looking to “start a rally with the Tigers only 22 runs behind,” the 43-year-old manager pinch-hit himself for Travers. A story, probably apocryphal, says that as Jennings stepped up to bat the umpire asked him who he was replacing. “None of your business,” Jennings said. Under these circumstances that was good enough for the umpire, who duly made a note on his scorecard and signaled “play ball.”

Jennings' at-bat was anticlimactic. “A nasty lad named Herb Pennock who happened to be pitching for the Athletics at the time showed his lack of a proper bringing-up by refusing to let [Jennings] hit the ball.”

He didn’t start a rally, but the manager’s strikeout greatly improved his team’s overall credentials. Thousands of iterations of major league teams have played without any Hall-of-Fame-caliber players, but the Tigers of May 18, 1912—the worst team ever—officially used one.

Despite the football score, the whole farce took just one hour and 45 minutes. Al Travers went the distance—eight innings, 24 runs, 23 of them earned, seven walks, one cautionary fastball, and one glorious big-league strikeout. It is the worst complete-game line for any pitcher in the record books, but Aloysius Travers is in the record books, where he will remain for all time the 3,684th major league player in history, a list that includes (among others) Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, Hank Greenberg, Mickey Lolich, Al Kaline, and Justin Verlander. Travers is on that list—and no less deserving of his place.

The game ended peacefully. After the last out, Travers’ nondescripts dragged themselves back into the clubhouse and shed their borrowed uniforms. Jennings paid them off, $25 for Travers and $10 for the others. Nolan, the sports editor, offered Travers some unofficial financial representation:

That night Mr. Nolan asked me how much I was paid and when I told him $25, he suggested I go see Mr. Jennings at the old Aldine Hotel the next morning. I did, and I received another $25 for my efforts.

Bill Leinhauser seemed to have gotten the same tip. He too presented himself before Jennings on May 19 and came away $15 richer.

The next day, a Philadelphia paper printed a picture of Travers—looking magnificent in a George Mullin’s uniform—under an unflattering caption: “Strike-Breaking Pitcher.”

“My mother saw that photo,” Travers remembered. “The next thing I knew she was yanking me out of bed, waving the paper at me, demanding to know why any son of hers was breaking strikes. I thought I’d lose my home, but she forgot all about it when I gave her the $50.”

In the conclusion: the fate of Ty Cobb and the striking Tigers, the end of our story…and a surprising postscript featuring Claude Lucker, the fan whose insults lit the fuse.

Perhaps because of the typographical sleight, Bill Leinhauser, a 40-year veteran of the Philadelphia Police Department, would later be instrumental in helping the Official Encyclopedia of Baseball document the correct details of his fellow players, ensuring each man received his rightful place in history.

We spent five fruitless minutes looking for another source to substantiate Maharg’s nickname. Doddles may even be a mistype of an entirely different great nickname: “Doodles.” In the end it’s up to you.

Wow, what a blowout! It’s a shame that Denny McClain couldn’t go in the wayback machine 50+ years! I was amazed at the ages of some of the replacement players. Very interesting 🤔. Thanks, Paul.

Thanks for the wonderful write up of a game I’d heard of but didn’t know much beyond that it happened.