Twisting the Tiger’s Tale - Conclusion

The fate of baseball’s first organized strike - and a last look at the man who caused it.

When we started writing this story, we thought we’d be in and out in two parts–light stuff around here. But it quickly became clear that we’d stepped into an epic, full of villains, other villains1, intrigues, people taking grand, hopeless swings, and all of the Progressive Era color you could want. The story kept going, and we kept writing. Thanks for joining us.

If you’re just arriving, here’s a handy chapter list:

Saturday, May 19, 1912

Ban Johnson, the American League president, was at a banquet in Cincinnati when someone passed him a note reporting the circumstances surrounding the Tigers’ May 18 loss. Johnson—a man with no appreciable sense of whimsy—was predictably horrified by the headline-making antics of Detroit’s replacement Tigers. The executive reportedly left the banquet without another word, bound for the train station and Philadelphia. After a late-night conference with the Athletics’ ownership, Johnson brought Al Travers’ baseball career to an abrupt end, announcing:

The Detroit club will not appear on the field again until I am assured that it has a set of good players who can compete with other teams. There will be no more farces in the American League.

Hughie Jennings, the founder of the farce, had no regrets. “I put a team on the field today to save the owners of the Detroit franchise from being fined $5,000,” he said. Mission accomplished on that front. “It is now up to President Johnson of the league and [Detroit] President Navin to settle with the strikers. I do not intend to take sides one way or the other. I am worried by the situation and when they take the burden of it from my shoulders I shall not be sorry.”

The final Detroit/Philadelphia game on May 20 was cancelled, and the striking Tigers’ had made their first labor kill. The Athletics were offered a forfeit, but Connie Mack declined to accept, “out of courtesy” to Navin (and not wanting to lose the game’s ticket sales). The teams could play it later, Mack offered, when all this unpleasantness was settled.

It was a small victory amidst a losing war. The end had begun on May 18, when the champion Athletics, whom the Tigers had tried hard to win over, instead bowed to Connie Mack and declined to join the walkout.

“The Athletics declared out yesterday as soon as they thought of the paychecks they might miss,” one commentator wrote, “and the easy victory they had in sight. No club that is up in the race will take a chance [on striking].” This quickly proved true.

“We all sympathize with Cobb,” said James Callahan, the White Sox’ manager, “and it is too bad such a thing as this has occurred, but…after both parties have cooled down, everything will be arranged to the satisfaction of everybody. Meanwhile, the Chicago team will indulge in no strike, but continue hustling for the pennant.”

Lots of moral support—no solidarity.

“All this talk of a general strike among ball clubs seems rather wild to me,” Tris Speaker said on behalf of the Red Sox. “It’s a bad thing for baseball that this should ever have occurred, but we figure that the Detroit club owners and Johnson will get together without delay and smooth out the wrinkles.” In this analogy the Tigers were the rumpled shirt and Ban Johnson the hot iron.

In the end, only two other teams, New York and Cleveland, sent representatives to the Tigers’ May 19 conference on unionization. The Indians’ rep, George Stovall, said his club sent him as a “gesture,” and that his talk with the Tigers did not include discussion of a players’ association. Instead, Stovall said he “counseled them as to their course, and advised them against any of the hasty moves they have threatened.”

This became the standard line—the Tigers had been too hasty. Why didn’t they work to get the League’s players to sign a petition calling for Johnson’s release? Why did they jump right to threatening a strike? Connie Mack thought he knew:

You can bet they never would have thought of striking if they were in the lead or any way near it. They are simply disgusted because they are out of the race and now they are in a humor to do anything.

Ty Cobb was still receiving plenty of support, including “enough letters and telegrams from fans of the country to fill a waste paper basket.” The mayor of Atlanta praised Cobb for “living up to the principles that have always been taught to Southern manhood…the defense of the sacredness of home ties and the memory of loved ones.” Another supportive letter arrived, signed by the entire Georgian congressional delegation.

But the man initially at the center of the standoff had quietly begun drifting to the periphery. Cobb was conspicuously absent for the big meeting, not appearing at the hotel war room until late that night. Several of the other players had left early, and those that remained seemed to have shifted from offense to defense:

“We made our move this afternoon, and the next move is up to President Johnson,” one said. “I do not see that we can do anything until Johnson makes his move.”

When no larger strike materialized, the Tigers were isolated, but they had managed to stick together, and there was some power in that. “I do not think that Mr. Johnson would bowl out an entire club,” Cobb said. “League presidents and managers have to listen to players some time, and this is a good chance.”

“The majority of the baseball public, every team in our league, except the Athletics, is with us in this fight,” outfielder Davy Jones added.

Johnson made quick work of that support by hinting he’d cannibalize the other AL clubs to reconstitute the Tigers and make the league whole. He called a Philadelphia meeting of his own for Tuesday, May 21. On that day all the owners in the American League were to convene in order to “secure players to take the places of the men who have broken their contracts with the Detroit club.” The tactical president said he “hoped” the other clubs would be able to “hold their own men,” but ruled nothing out. The prospect of Johnson and Navin raiding the other teams made the Tigers’ strike everyone’s problem.

The players put on a brave face, predicting disaster if Johnson followed through. “Let them try it,” shortstop Donie Bush said. “They might as well keep the gates closed as to put a substitute team on the field at Bennett Park. The entire town is with us to a man, and such a move would prove a rank fizzle.”

Hughie Jennings was not so sure. After what Ban Johnson termed “a very enjoyable two hours’ talk with Hughie,” the Tigers’ manager made his public break from the strikers, saying he would manage any team put in front of him.

I can recruit players from the substitutes of the other AL teams if [the owners] decide to stand by President Johnson in the matter, as I believe they will. I might not be able to get as good a bunch of players together as I have now, but you never can tell. I might be able to get a lot of good material.

In baseball’s first game of labor chess, Johnson now had the Tigers in check, but checkmate had to wait on Frank Navin’s late-arriving train.

Monday, May 20

Even though he beat Navin to town by 24 hours, Johnson had declined to meet with the players directly, seeing it as beneath his office. As Johnson saw it, disciplining Cobb for misbehavior was his job, but getting the players to play was a job of the team’s owner.

Navin arrived early in the day on May 20. His first stop was the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, where he met with Johnson, ostensibly to consult, but mostly to receive orders. Johnson told Navin he wasn’t budging an inch on Cobb’s suspension, but in a gesture of conciliation he would forgo suspending the other Tigers for the rest of the season if they agreed to end the holdout and return to action for their scheduled game in Washington D.C. the next day.

Navin headed to the Aldine Hotel to meet with the players. The first and only real negotiation session of the strike lasted about two hours. The owner reportedly opened with “a personal appeal, telling them he was the principal sufferer in the affair and he did not feel that it was just to him.”

But he also empathized with their concerns and made a series of non-binding pledges, saying “he would do his utmost to have Cobb reinstated as quickly as possible and that he would do all he could as a club owner to have the AL provide better protection to the players on the field.” Navin offered one formal concession—if the players ended the strike, he would pay whatever fines Johnson imposed on them.

It wasn’t much—and it might not have been enough. The players had come a long way and some among them, like Davy Jones and second baseman Ed Delahanty, were in it for the long haul. Delahanty, likely understanding crossed the Rubicon of his career, had become more and more strident in pushing for collective action and a union. Some papers had begun referring to him as “Chairman Delahanty.”

“I’m strong for a union,” he said. “In fact I believe that is the only way in which we can bring our grievances to the front. We must have protection, and we must start the agitation for a union right away.”

Delahanty might have nursed the action along a little longer, but after listening to Navin, Ty Cobb, probably already suffering from striker’s remorse, addressed the players:

I can’t tell you how much I appreciate the way you have backed me up and stuck by me—and I know you would go through to the finish with it—but I don’t want to take the responsibility of having all you good fellows fined and blacklisted. So I hope if you can see your way clear you all will get back into the game and play for Mr. Navin—and win. I’ll be with you soon, I hope.

With Cobb’s urging, the majority of the players agreed to take the deal on the table and end their strike. It would be 60 years and one Marvin Miller until the next one.

The Tigers escaped the showdown with their dignity intact, but the prospects for a robust Players’ Protective Association immediately dimmed:

“Whether there will be any organized movement among the players to have grievances adjusted, none of the Detroit men would venture to say.”

Still suspended indefinitely, Cobb traveled with the team to Washington on May 21 but then announced he would return to Georgia.

“If Johnson should decide to lay me off for a month or the remainder of the year, I will be perfectly satisfied. My action in New York was simply on a principle and the Detroit Club will be the sufferer. My pay goes on, no matter whether I play or not.”

That same day, Johnson announced that every player who participated in the walkout would be fined $100, $50 for each game disrupted. The only participant not fined was Ty Cobb, as was ineligible to play in either game.

With the strike finally ironed out, Johnson returned to his New York office and began a cursory investigation of the events of May 15, when Cobb went into the stands and attacked Claude Lucker, the fan who’d been tormenting him.

On May 25 Johnson reinstated Cobb and fined him $50. In doing so, the executive reiterated that the fault lay with the player and not with the fan.

“Cobb did not seek redress by an appeal to the umpire, but took the law into his own hands,” Johnson declared. “His language and conduct were highly censurable,” no matter what provocation had occurred.

Johnson too made non-binding assurances that the American League would do more to protect spectators from abusive fans and increase overall security within its ballparks.

Later that summer, the victorious president even blessed the players’ desire to form a little club. Of course, he said, “a players’ union modeled along the lines of the labor unions would hardly be tolerated,” but if they wanted to get together and talk amongst themselves, have at it.

It was a free country, after all, and people had rights.

As his run-in with Ty Cobb rattled baseball’s halls of power, Claude Lucker’s 15 minutes of fame turned into more like 20. The same day the Tigers struck over Cobb’s suspension, Lucker was interviewed at his place of work, 114 Centre Street in Manhattan, where he acted as a clerk and secretary for a retired sheriff and Tammany Hall political operator named Tom Foley. A reporter described Lucker as “a man of medium stature, stockily built, with a round, jovial face and merry eyes.”

Lucker was “still limping around painfully as a result of his encounter with [Cobb].” He showed off wounds on his leg, left side, behind one ear, and “a lump on his forehead where he first felt the impact of Cobb’s fist.”

Lucker again told his story of the assault—which now included a group of Tigers following Cobb into the stands waving their bats—but other new details seemed credible enough:

When the Detroits were in the field for the third inning the boys kept it up on Cobb. Still there was no harm in what was said. I had an alpaca coat and he seemed to single me out, for he yelled back, “Oh, go back to your waiter’s job.” But that did not harm.

Lucker continued insisting “there was nothing said back at Cobb half as bad as what he said himself—and he said it first.”

The New York fan also clarified why Cobb had never been arrested—he had not pressed charges. “Some of my friends wanted me to, but I didn’t want that done. He would probably have got off with a $10 fine anyway.”

Reporters also talked to Foley, identified as the “Tammany leader of the Second Assembly District.” After promising he had little to say on the matter, Foley’s boss uncorked a fine monologue.

If a great baseball player like Ty Cobb can resent the catcalls and ragging of the bleachers by climbing over the rail and assaulting one man—and that man a cripple with one hand gone and three fingers of the other missing—then it is time for the public to stay away from the game.

Foley seemed fixated on Lucker’s disability, bringing it up repeatedly…and perhaps causing his secretary some discomfort.

I do not believe that Claude Lucker, whom I have known for a great many years and whom I took in as an office assistant after he had been crippled…, ever uttered anything which could be interpreted as a personal insult by Mr. Cobb.

A day later Lucker was reluctant to discuss the Cobb case, and while the reporter eventually got him to talk, it was clear that the man was “sensitive about his affliction.” Lucker didn’t mind being portrayed as the avatar of baseball’s grandstand “muckers,” but he resented how his public identity was being hung on his disability. “I am not looking for sympathy,” he told the reporter.

I work every day and I have acquired the knack of holding a pen or pencil between the thumb and forefinger of my right hand so that I can perform secretarial duties. I am tired of seeing every newspaper represent me as absolutely helpless or infirm.

Lucker said legal action against Cobb was forthcoming, but according to SABR researcher Kevin Barwin, “It is not known if Lucker ever followed through with any legal action against Cobb,” nor do we know why Lucker might have changed course. The man was no stranger to litigation; in 1913 he won a $15,000 award in a lawsuit against his former employer, the New York Times, for the accident that cost him most of his hands.

Lucker’s time in the spotlight was over, but he did have one more splashy encounter with history.

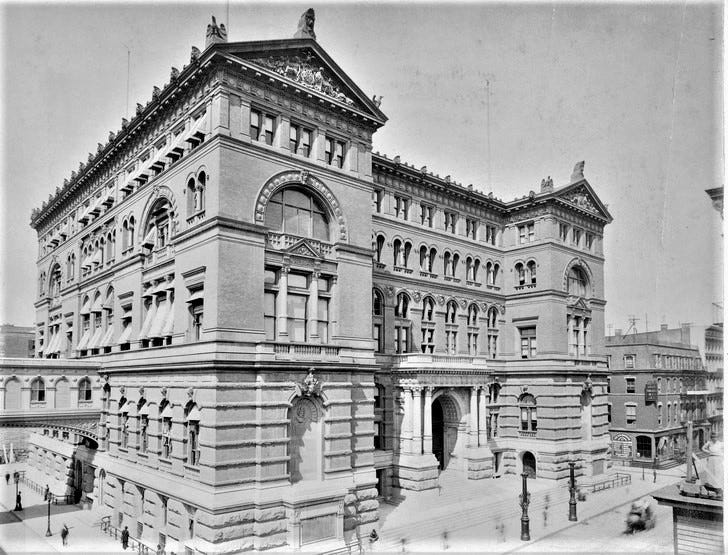

On November 14, 1914, someone placed an improvised bomb under a bench in the Centre Street Police Court in New York’s Criminal Courts Building. The bomb was made from an oil can “stuffed with two pounds of black and smokeless powder and thirty bullet cartridges of various calibers” and connected to a three-inch, slow-burning fuse.

Just before Magistrate John Campbell took his seat behind the bench, someone lit that fuse and slipped away. Campbell was known to be vigorous in his sentencing of convicted anarchists, and some anarchist groups were at the time embracing what was called “propaganda of the deed,” their version of which we’d today call “acts of terror.” Just a few days earlier, operatives from this movement had attacked another judge in the Bronx.

Waiting to process a prisoner, NYPD Patrolmen George O’Connor noticed smoke coming from under a bench, where he found a package wrapped in newspaper, the fuse “spitting and sizzling, sparks setting the paper on fire.” O’Connor tried blowing the fuse out, and when that didn’t work he ripped it out completely. Not knowing what was in the package, he grabbed it and ran out of the courtroom.

“O’Connor sped out into the rotunda, dashed through the great doors, and down the long flight of steps,” throwing the package into the safest place he could think of on short notice—the middle of Centre Street.

Meanwhile, tenants in the nearby office buildings were realizing what had happened, leaving them “in an agitated frame of mind.”

They could see the bomb down in the gutter and they didn’t know when it might explode and blow them off the map. In this emergency it was Claude Lucker, a clerk in the office of former sheriff Tom Foley, who displayed initiative.

Lucker arrived on the scene carrying a bucket of water. While others watched or cowered, Tom Foley’s famously “crippled” employee approached the bomb, doused it, and went back inside to refill. The tactic inspired Patrolman O’Connor, who picked up the “infernal machine” and gently slid it into the refilled bucket, effectively ending the danger.

We’ll be off next week, working on a presentation we’re very excited to give at SABR 53, the Society of American Baseball Researchers’ convention.

If you’re attending that conference later this month, we’d love to see you on Saturday at 10:00 AM, when we’ll spend 20 minutes charting the many comings and goings of itinerate mesmerist catcher Billy Earle, and looking at the hard life of a haunted player at the end of the 19th century.

We can’t say we identified anyone we’re comfortable calling a “hero” in this story, but your mileage may vary.

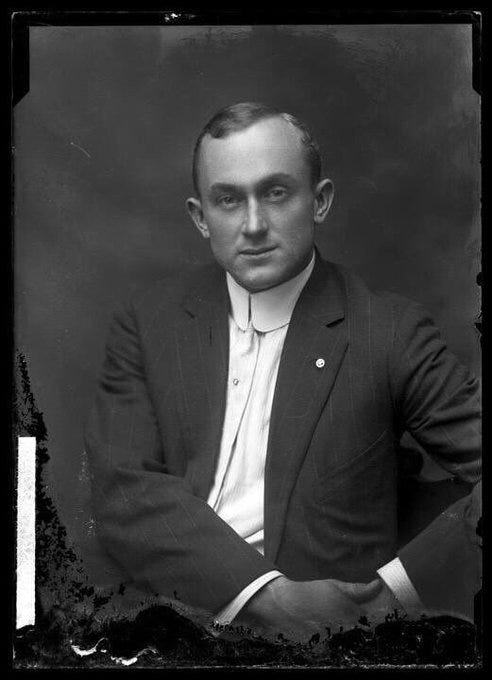

No true heroes but I guess Lucker and Patrolman O’Connor combine to make one hero. Lucker had the proverbial cloud following over his head; he certainly wasn’t a likable character. That photo of Ty Cobb was very ‘period’: he looked very mysterious. Paul, I subscribe to another baseball Substack called Lost in Left Field by another Paul (White). While both of you report on baseball history, you get the story behind the story and he has a lot of stats and comparisons. I enjoy both. Funny, when I subscribed to LILF, I didn’t pay close enough attention and saw Paul and thought it was you!

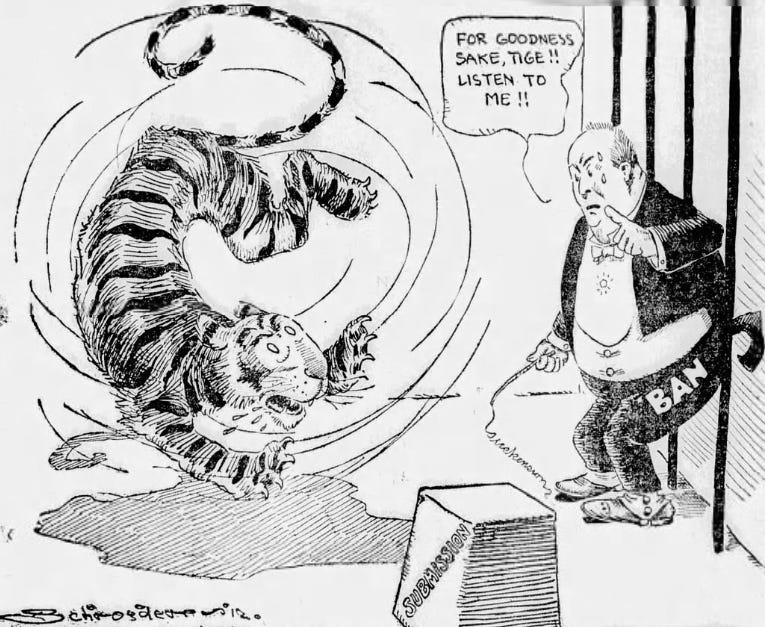

That is a classic cartoon, Paul. Newspaper cartooning is truly a lost art.