Two Postscripts

An epilogue to our story on the hot pants craze and perhaps the prologue to some stories to come. Plus, words from our favorite baseball researcher!

It probably won’t happen often, but we’ve come to the realization that sometimes Project 3.18 will need to circle back. We see two main reasons this may be necessary, and today we have a chance to highlight both.

We hope you have already read the stories we’re about to build on, but if you missed either of the originals, we know you will enjoy those, too, and we’ll include a link to each for your convenience.

Postscript: We are All Susie

In some cases, after publication, we’ll come belatedly across a detail or follow-up episode too good to leave behind, even though it missed the first train. If a detail or vignette is too good to pass on but not substantial enough to be its own story, it must be a postscript.

Required Reading: “Good Legs and Guts”

Our story on baseball’s “hot pants” craze also glanced off of a few related cultural phenomena we did not get to fully cover, busy as we were looking up first-wave feminist movements and teaching ourselves to knit.

One of these flyby moments addressed the evolving job of the “basepaths-sweeper,” changes that drew the fiery scorn of Project 3.18 hero Barbara Dell Hall of Rochester, New York, after the minor-league Red Wings hired two women to sweep the basepaths midway through the game, and put them in hot pants, too. “If a sweeping attendant is a necessary safety measure,” Hall asked in 1971, “then why not employ a capable person regardless of sex?”

The Atlanta Braves were clearly reading the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle that day, and they took her pointed question to heart. But first, a little background on the groundskeeping role she called into question.

It turns out that “sweepers” were a thing in baseball long before 2022, when every starting pitcher started working on one in spring training. We’re not sure if this can become its own story yet—the second in a most-unexpected series exploring gender norms and frictions in 1970s’ baseball—but we can tell you that in 1972, the Atlanta Braves “joined the list1 of baseball clubs adding a bit of diversion to the game—mainly a shapely young lady who dusts off the bases midway through the contest.”

The Braves hired 18-year-old Susan Whitted, a freshmen cheerleader at Jacksonville University, who wore hot pants (of course), swept around the basepaths, and according to various considerations ended up giving players a kiss on the cheek or a swat on the butt with her broom.

“Susie the Sweeper” might best be seen as some sort of underdressed clown (in the performative sense, not the pejorative sense), ostensibly with a real groundskeeping duty but in reality there to titillate and amuse with exaggerated little performances and a fair amount of tumbling and cartwheels (Whitted was an accomplished high school gymnast). “Susie the Sweeper” was such a hit that when Whitted departed after that season (we choose to believe this was because she wanted to focus on her studies), the Braves hired two women to replace her, and they decided to call them both Susie, when neither actually was Susie.

So, perhaps more on Susie (and her brethren across baseball) in the future, but for today that’s the context you need to understand what a “sweeper” was to fans at Atlanta Stadium on August 14, 1972.

That day, a middling Braves team would try to win their four-game series against the very-good Cincinnati Reds. And by 1972 there were many Very Good things about the Reds, but their catcher, Johnny Bench, might have been the Very Goodest, midway through his second MVP campaign and having either his best season or a close second. He was also just 23 years old, consistently leaving people who saw him play with the impression they’d just seen something very special.

August 14 also featured a bonus contest. Before the main event, the Atlanta Braves would take the field against their wives for a two-inning softball game. The Braves’ wives had their own custom uniforms, which of course featured hot pants, or at least shorts. This is the second such contest we’ve come across in 1972; the White Sox did something similar and we can tell you the Sox’ wives were definitely wearing hot pants, and boots that seemed sub-optimal for softball.

And so these domestic games are the second inter-gender baseball happening we might look a little more into for the future, to see what they can tell us about the people who played in them and what, if anything. they reflected of broader culture. If we find enough fun stuff, we’ll share it, and if we find fun stuff and meaningful social commentary, we’ll definitely share it.

The Braves, in the spirit of fun, had lined up a basepaths sweeper for the midpoint of the softball game, but with a little twist. After the public address announcer introduced “The Basepath Beauty,” instead of a vivacious co-ed tumbling out onto the field, it was the best player in the National League.

And while many outlets (including this publication) teased Johnny Bench as having appeared in hot pants, that wasn’t exactly true. He wore his uniform jersey on top (including cap), and on the bottom he wore a pair of “white boxing shorts trimmed in blue” and his usual athletic socks and cleats.

Still, this outfit and role was a lot to ask of a public-facing masculine icon. The Braves had also planned one of their own players to join the bit, performing as a version of Morganna Roberts (the notorious trespasser who broke into sporting events throughout the decade to do things to players we’d clearly label as sexual harassment today) and chase the Basepath Beauty off the field. But pitcher Tom Kelley couldn’t go through with it and “backed out at the last minute”—they probably asked him to wear a wig.

Afterward, Bench had no regrets. “I didn’t mind doing it. It was for a good thing,” he said. We weren’t able to figure if there were charitable implications for the softball game but that seems plausible. “The Braves’ front office asked me about doing it yesterday and Sparky [Anderson, the Reds’ manager] said it was up to me. I told them, ‘Let me talk to my agent,’ so I went up to [Reds coach] Alex Grammas.”

Bench’s newly-deputized agent didn’t even bother to negotiate. “I said ‘Sure, go ahead, I wanna see you do it.’”

“You got to hand it to him,” Sparky Anderson said. “Not many guys of his stature would agree to do something like that. But I tell you, when he started over toward first base and I saw those wives standing over there on the sidelines, I said to myself, ‘Oh boy, please don’t grab one of them.’”

Not only was this a risk, given the real Susie’s typical routine, it was an option the catcher himself considered. After agreeing to perform the stunt, Bench jokingly told several Braves players he was trying to decide which wife he would kiss. “But the wives weren’t actually on the field, so I kissed Quarry.”

That would be the celebrity guest umpire, Jerry Quarry, a heavyweight boxer who was spending the summer building his brand in between matches with Muhammed Ali. Susie, known to occasionally kiss an umpire herself, would have been proud.

Bench’s performance (he did the sweeping part, too) delighted the crowd, who then got to watch “the feminine mystique take its toll,” as the Atlanta Journal2 put it. The wives beat their husbands 8-0.

The baseball gods clearly had opinions on what they’d just seen. Bench, who had been stuck in a 2-27 slump, hit a two run home run in the first inning and just missed a cycle, adding a single and a double.

“I swept the cobwebs off or something,” he said. He finished with five RBIs as the Reds won the intragender contest 12-2. “I missed one hanging slider or I would have had eight.”

Meanwhile, Tom Kelley, the erstwhile Morganna, gave up five runs in three innings of relief work. The baseball gods had clearly wanted to see him in hot pants, or at least a brassiere.

Postscript: Frownfelter Speaks

Perhaps the most worthy reason to circle back is if we have managed to connect to someone who previously showed up in our writing!

Note: The editorial plural has been deactivated for this one.

Required Reading: “Now That’s What I Call a Forfeit”

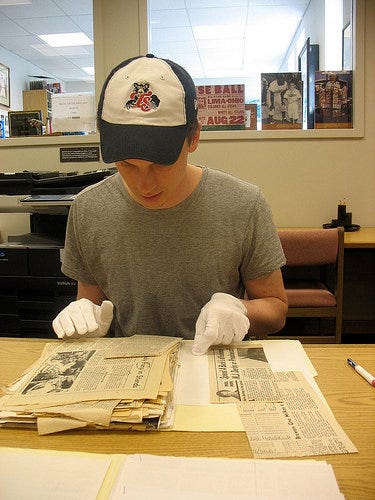

Back in February, after I published my overview of forfeited games, I decided to reach out to one of my longtime muses, Gary Frownfelter, the stoic baseball researcher behind the comprehensive list of forfeited games hosted on retrosheet.org. Frownfelter’s shorthand reports on baseball’s “games that weren’t” inspired not just my own forfeit writing (where I sought to do the opposite), but a lot of what eventually became Project 3.18, and I wanted to thank him for doing the methodical, challenging work of excavating and preserving history and in doing so making my own creative work possible.

In a legitimate, non-creepy way, I found Gary’s email address and sent off a little introduction/thank you, and a link to the forfeit piece.

And he wrote back! Saying, in part:

Wow, I did that paper a long time ago. You make it sound that it was a super complicated project.

These are the words of a man who finds himself receiving overenthusiastic attention from an internet stranger for something he has almost forgotten about and is feeling both wary and flattered. Because he is a nice person, Gary told me a little about the project, adding the typical critical reflection of an artist appraising early-career work:

Also, some of the summaries could have been a little more complete.

Receiving his response, I plucked up my courage and asked Gary if I could send him a few more questions about his forfeit research project, with an eye to including them in a future piece. I crossed my fingers and hit “send.”

43 days later, I had his answers.34

P3.18: Can you talk a little bit about when and how the forfeit project started, how long it took, etc.?

Frownfelter: I was reading a book on the Philadelphia Athletics and ran across the July 20, 1918 forfeit (the seat cushion game). That got me curious as to what really happened. I was doing some volunteer work for Retrosheet at the time and had access to an electronic newspaper archive (Quest). I looked it up and noted the information. In the game description of that game, another forfeited game was mentioned. I started to build a list. I eventually went to the online game logs and identified all of the forfeits listed. I looked each up and added it to my list. It took me about six weeks to put the list together. There was no expense because I was able to access the data I needed on-line from home. When I couldn't find any more, I submitted the index to an editor at Retrosheet, and he put it online. Other people have added to it since then.

Ah, the research rabbit-hole. If you are a regular reader here (or even if you read just our first postscript today), you know how much fun Project 3.18 has in these warrens. Gary also points out one of the Rules of Forfeit Journalism, maybe the only rule: “In your coverage, mention the most-recent forfeit.” Happens every time.

Next, I asked Gary a follow-up question that has long troubled me, and one I am a little embarrassed not to already know the answer to:

P3.18: WHY were there seat cushions available at games in the early part of the 20th century?

I do not know for sure but I think the fans could rent them for the game.

Don’t worry, Gary, Project 3.18 resolves to get to the bottom of this and report back. In tribute to Mr. Frownfelter, the next forfeit piece will cover the 1918 “seat cushion game,” and after that I promise to finally leave him alone.

If you happen to already know anything about the history of removable seat cushions at baseball games, please do mention it in the comments.

P3.18: Do you have a favorite forfeit?

Frownfelter pointed to that darling of the auteur, the August 7, 1906 contest between the New York Giants and the Chicago Cubs at the Polo Grounds. John McGraw was healthy and present for this one, and you can see how the day added a great deal to his already-notorious reputation.

I’ll let Gary tell it, from his original report:

The trouble really started in the game the day before. Umpire Jim Johnstone removed manager John McGraw and third baseman Art Devlin from the game over a disputed call. The crowd objected and the police had to escort the umpire from the field after the game. A half-hour before the scheduled start of the August 7 game, Johnstone arrived at the Polo Grounds to assume his duties, but was denied entry by the club.

He immediately called the game a forfeit in favor of the Cubs. The other umpire assigned to the game, Bob Emslie, had already entered the grounds, but by league rule, quickly left when he heard of Johnstone's situation. At the scheduled game time, the Giants took the field and, not seeing an official umpire in the stadium, appointed one of its reserve players as umpire, as was the custom. The Chicago team refused to take the field and bolted for the clubhouse. McGraw and his appointed umpire declared the game a forfeit for New York. The New York club later claimed that the police requested that the umpire be barred because of a fear of a possible riot. This was denied by the police. National League president Harry C. Pulliam ruled with the umpires and the forfeit to Chicago stood.

What a hot mess. I’ll put it on the short list.

P3.18: At this point, in terms of the leagues that are covered in your research, do you think we have captured ALL the forfeits, or might there be some still hiding out there in the distant past when recordkeeping was poorer?

Frownfelter: I see that a forfeit was added to the list in 2021. As more newspapers become available online, there will probably be more found. ... There is a fine line between a forfeit and a team just quitting. Most of the forfeits were just petty disputes.

The recent discovery came from July 23, 1901, a game I coincidentally mentioned in the inaugural forfeit post. 1901 is the dawn of “modern” baseball, by which point both the game and its records had reached a level of consistency. And yet, the details of that day’s forfeit were forgotten for 120 years. Yes, in this line of work, we’ll need to circle back from time to time.

As I suspected, Gary had a secret identity, one which now, safely in retirement, he was willing to reveal.

P3.18: What do you do/did you do in your professional life besides baseball research?

Frownfelter: I worked for a statewide healthcare / hospital system in the Information Technology area for 28 years. I was on the management team that oversaw the merger of organizations and helped define policy and procedures. I lead a small group of IT software developers that assisted various departments in the hospital to define administrative procedures and design and wrote small computer applications to help implement them.

They walk among us, these secret scribes and defenders of history, quietly overseeing technology systems integration projects by day, and building a single comprehensive record of baseball forfeits by night.

P3.18: Are there other areas of baseball history or research that interest you? Have you had any other papers or projects published or posted somewhere online?

Frownfelter: I am writing a book about the history of baseball in Flint, Michigan. I have done the research and have written most of it. I just need to finish it up, and get it edited and published. Baseball has been played in Flint since 1866. The city has had several minor league teams, the last one in the early 1950s. It also had a strong semi-pro presence in Michigan.

I enjoy history and I think it is important to remember what has gone on in the past. I have collected data for Retrosheet's box score project and scored many games for them. I volunteered at the local museum. When I decided to write a book, we were sitting at lunch at the museum talking about new exhibitions the curators wanted to put on. Someone mentioned a baseball exhibit and we asked, “What about baseball in Flint?”

We looked in the museum archives and found only three things:

A uniform that we think was worn by a player for a Flint minor league team in the 50s;

A baseball that had "No Hitter" written across the sweet spot with no date or name or other information;

And a bowling pin that came from a bowling alley owned by a man that owned a team in the 1920s.

Flint's last team went out of business over 70 years ago and nobody at the table knew anything about Flint baseball.

This anecdote sums up my deep and fervent appreciation for the minds of historians and researchers. Were I to come across that little hodge-podge, my reaction would be “Well, I guess we don’t know anything about Flint baseball. What else we got?”

But people like Gary Frownfelter see an old baseball, a uniform, and a piece of ephemera from an unrelated sport, they squint, and they say: “I think that might be the start of a book.” Such an instinct for what lies within—and the willingness to dig it out, sort through it, and preserve it—has left us all we know of human culture and scientific knowledge, so the next time you see Gary, please say “Thank you!” But, like, be cool about it.

While Project 3.18 remains committed to accessible, “walk-up” storytelling, we certainly feel better having established a format suitable for some worthy add-ons. We hope you enjoyed today’s mash-up featuring two of the all-time greats.

Next week, we’ll have a new thematic ejections piece to share, and it’s a fun one. Prepare to get down, because that’s what all our ejectees will be doing, one way or another.

On May 20: “Repose”

One day we may need to run down that list. For posterity, you understand.

The Journal article also added one additional contribution to Project 3.18 scholarship: the record of another Hot Pants Day in 1972, hosted by the Braves. We wanted to mention it, in case you are keeping score at home.

Gary’s responses got lost in his drafts folder for a while. Baseball Researchers, they’re just like us.

In a related note, Frownfelter’s responses have been lightly-edited for presentation here.

“Johnny the Sweeper” - that probably looked good on his resume.

Well, I for one, think Johnny Bench has some great legs! I was 14 and lived in Atlanta in 1972 and really wished I had been at that Cincinnati Reds Atlanta Braves game to see Johnny sweep! 🧹