Work, Fight, or Forfeit - Part 2 of 3

In which wartime baseball is so busy with drill practice that it forgets to engage in the REAL national game: special-interest lobbying.

It’s Part 2 of a story of baseball and society during World War I. Thanks for coming back for a second serving. The other day, a friend told us that sometimes he just starts reading without checking if there’s an earlier installment and ends up a bit lost. We don’t recommend that, so be sure to check out Part 1 if you haven’t read it.

Here’s a link: Work, Fight, or Forfeit - Part 1

In the wake of Provost Marshal General Crowder’s confirmation that baseball players must indeed perform “useful” work at home or fight in Europe, Ban Johnson, president of the American League, seemed disinclined to do either.

While the ruling came out of a clear sky, so far as our knowledge of the government’s wishes was concerned, we accept [it] without protest.

With that obligatory preface, Johnson began his veiled protestations:

If those 255 players affected can perform useful and indispensable work in the remaining three months of the baseball season, the financial loss resulting to our business is inconsequential.

Johnson seemed confounded. Hadn’t baseball earned a free pass? A full year before, as the government urged “preparedness” from all Americans, the AL president made his players conduct close-order drills and marching exercises during spring training, even offering a $500 prize to the best-showing club. The players used their bats in lieu of Enfield rifles. Drill presentations became a regular pre-game fixture in the next two seasons, sometimes led by friendly government officials, including the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The demonstrations aimed to show officials that players could stay “prepared” while staying on the field.

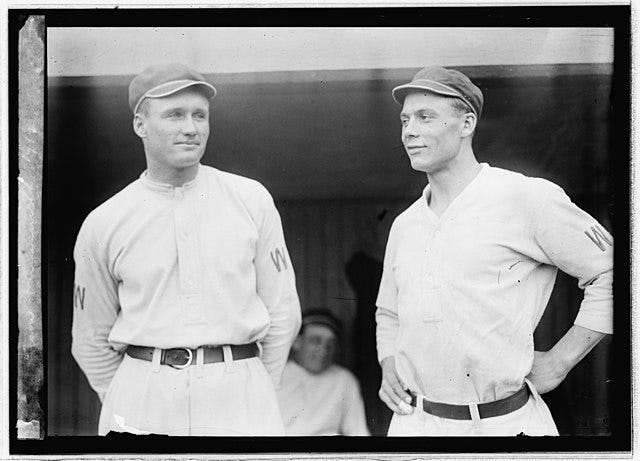

Clark Griffith, manager and part-owner of the Washington American League team1, had a higher profile in the nation’s capital than many of the league officials based elsewhere across the country, and he instinctively took a lead role in trying to keep the federal government happy, on and off the field.

During the war, Griffith established a Bat and Ball Fund to raise money to send baseball equipment and supplies to soldiers fighting in Europe and training in the United States. The first shipment abroad was lost when the merchant vessel carrying it fell prey to a German U-boat, but eventually Griffith got nearly $100,000 of balls, bats, catching equipment and score cards delivered to America’s new citizen-soldiers.

To promote the fund, Griffith often scattered several hundred bats and baseballs on the field at his eponymous stadium and invited thousands of servicemen to try for them, showing that ill-advised giveaways are not a recent promotional innovation. Once, after giving the sign to go, Griffith was forced to give “an imitation of a German, running from the soldiers as they came on like stampeded horses.”

The Nationals’ manager also kept box seats available for members of the armed forces, and both the rank and file and even some of the top brass visited regularly. Maj. General Peyton March, the Army’s Chief of Staff, was mad for the game, even at the peak of the war. Attending one soggy Nationals game in late June, 1918, “March was rained out of his box five times and came back every time,” The Sporting News wrote, commitment which revealed him to be a True Fan. Unfortunately for baseball, March’s day-job afforded him no say in the game’s wartime fate.

Throughout the major and minor leagues, teams invited the government to use the game and its ballparks as a platform for raising money for the war, a tactic which the vexed Ban Johnson revealed was as transactional as it was patriotic:

I cannot understand the statement that the game is ‘nonproductive’ when the two major leagues will deliver to the Government a war tax in the neighborhood of $300,000. The ball players, umpires, club stockholders and officials have bought more than $8,000,000 of Liberty bonds and have subscribed thousands upon thousands of dollars for the Red Cross and other charities. Where is there another class of men earning so much for the Government?

But all of these efforts ultimately failed to stir sympathy in Enoch Crowder, if he even noticed them. To the Provost Marshal General, baseball was just a game, and domestic amusements had little value in wartime, no matter how well they marched.

Most of Crowder’s work-or-fight order was quickly accepted by the public. Few in the mainstream press seemed to question the underlying logic of the rules—nobody felt the need to stand up for the “slackers” and the pool players. But the inclusion of baseball stirred much (carefully-parsed) discussion.

“Baseball,” one sportswriter wrote, “is the one sport that every American understands and the one sport that appeals to all in this country. Eliminate any other sport (horse racing was mentioned) and you will strike only a certain class, but eliminate baseball and the whole country will be affected.”

Pressed to say whether they were truly committed to eviscerating the national sport for war purposes, both Crowder and his boss, Secretary of War Newton Baker, employed an evergreen administrative dodge:

“Local draft boards [are] given discretion,” Baker said, “as to whether deferred classifications should be taken away. Each case will be decided separately and on its own merits.”

And thus was the buck not only passed, but cut–into some 300 pieces–and spread all over the country.

Meanwhile, the leagues wanted the Secretary of War make an overriding decision, hoping that as one man (and as a publicly-accountable official), he would be unwilling to dispatch the national game after being formally asked save it. The game’s leaders decided to focus their efforts around a single player with a compelling case and use the draft’s appeal procedures to push that “test case” back to Baker’s desk as quickly as possible, before local draft boards nationwide could find the rest of the players and begin ruling against them.

But which player to rally behind?

In 1918, Edward Wilbur Ainsmith was an eight-year veteran, a catcher for the Washington Nationals, and one of those baseball characters whose thumbnail biography threatens to trip a circuit breaker. Ainsmith was born in Tsarist Russia, making him one of only a handful of Russian-born major-leaguers, though he came to America as a very young child. He reached the majors in 1910 with Washington, where he became Walter Johnson’s personal catcher. He had a 15-year career in the big leagues, though mostly as a part-time player. After retiring in 1925, he led an ill-fated tour of women ballplayers around postwar Japan and later spent a year coaching the famous Rockford Peaches of the All American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1947. Here in 1918, Ainsmith became the bellwether in the debate on baseball’s national significance and societal worth. Oh, and his nickname was “Dorf2.”

Who selected Ainsmith to be baseball’s “test case” is not perfectly clear, but it’s fairly easy to see why they did. On July 1, Crowder’s work-or-fight rules went into effect. On July 4, the Washington Post reported that his wife (her first name, Julia, was not given, but we worked that out for ourselves) had died in hospital after a long illness. Eddie and Julia had a three-year-old daughter, Ann, who was suddenly reliant on her baseball-playing father3 for care and support.

By chance(?), right around the time that Julia died, the District of Columbia’s local draft board No. 9 called Ainsmith in to review his draft exemption and assess whether he was engaged in useful work. This made the catcher one of the first Nationals players to receive such a summons, and the first called by a D.C. area draft board (because he made his home in the same city where he played; not all players did). Put all of that together, and baseball had its man.

On July 11, less than a week after Julia’s death, Ainsmith stood in front of the draft board, accompanied by his manager, Clark Griffith. Ainsmith claimed that given his highly specialized baseball skills, “he had not perfected himself in anything else in which he’d be able to earn a good living.” It is not clear whether he cited his wife’s recent untimely passing in making this personal argument.

Griffith also spoke, ostensibly on Ainsmith’s behalf but in truth he was speaking for the sport as a whole. He “raised no technical point of law” in his remarks, instead urging the draft board to recognize that “from the standpoint of the public, baseball is an essential.”

To the surprise of no one, the board turned Ainsmith down, saying essentially that their hands were tied by Crowder’s work-or-fight rules. The board ordered the ballplayer to “find a useful occupation or be reclassified ‘1A’ and subject to be immediately called to the colors.”

The very next day, Griffith submitted a written appeal of the decision with a flourish, personally delivering it to the White House and the attention of President Woodrow Wilson, who gingerly forwarded it to Baker at the War Department. With that prudent bit of presidential delegation, the Secretary of War now had no choice but to weigh in on baseball’s role in American life. Essential and useful to the public good? Or just a silly game?

Newton Baker may have been the exemplar of the United States’ tradition of civilian oversight of the military. Slight of build and poor of vision, he had been turned down for service during the Spanish-American War and was allowed to pursue his own career in the law without interruption. He didn’t pursue Sitting Bull, but he was elected mayor of Cleveland, and if you’ve heard of what is today the nationwide law firm of BakerHostetler, yep, that’s him.

President Wilson appointed Baker Secretary of War in 1916, largely because neither the nations’ hawks or doves could find any quarrel with an unassuming domestic politician. He proved to be a superb administrator and bureaucrat, capably and dispassionately leading the military through a conflict of unprecedented scale, despite having known nothing about it when he took office.

In July 1918, finally forced to reckon with baseball’s relevance as a national game for America, Baker revealed he knew even less about baseball than he had about the military.

“Obviously,” Baker wrote in response to Ainsmith’s appeal, “baseball players are persons occupied in a sport, so that the ruling of the local and district boards must be sustained as plainly correct.”

The secretary could have stopped there, but he went a little further and in continuing, he revealed some pretty large blind spots:

While the number of men affected by the order may be sufficient to disorganize the business, many of the players are beyond the present draft age and it is by no means certain that complete disorganization of the business would follow.

In 1918, the draft targeted men aged 21-31. Anyone who knew even a little about professional baseball would have understood that most of the best players fell into that demographic; in the major leagues, it was 80-90%. But Baker did not know that—he would admit as much later on. And nobody bothered to tell him.

Concluding his ruling, Baker responded to Griffith’s argument that disrupting baseball would ultimately do more harm to the “fabric of the nation” than the country would benefit from forcing players into more productive work:

...the demands of the army and of the country are such that we must all make sacrifices…and the country will be best satisfied if the great selective process by which our army is recruited makes no discriminations among men...

To the sporting world, it was a deeply-dispiriting outcome. “Possibly Mr. Baker is of that makeup which recognizes nothing in this life as play,” The Sporting News groused.

We know nothing of his habits and how he spends his leisure hours, but we are led to suspect that he may be one of those who thinks that time relaxing is time wasted.

The outcome of the Ainsmith appeal shocked the baseball magnates, who’d allowed themselves to believe that Crowder’s lack of sentiment for their product was a fluke. Johnson and the game’s other leaders had misjudged their sport as “too big to fail,” and while that day would come, it was still a generation away.

When baseball became vulnerable again with the onset of World War II, the organization had a commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis4, whose job was to champion the game to the government and the public; and a president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who knew the game and loved it since he was a boy. Roosevelt also understood how it worked, how much it cost, and what it meant to many Americans, and all of this was reflected in his decision to deputize baseball as an agent for keeping up national morale.

But in 1918, Crowder and Baker had no such affections, nor even a nuanced understanding of how the sport functioned. And unlike Roosevelt, they hailed from the perhaps the last generation of American leaders who might have been able to escape their formative years without learning a thing about baseball, let alone taking an interest.

The Secretary of War would later admit some level of personal ignorance, and do some veiled protesting of his own, saying that he and Crowder “had been forced to rely almost entirely on their own (scant) knowledge of baseball conditions” in deciding the game’s wartime fate.

Maybe Ban Johnson didn’t have their number.

Having failed to educate these men beforehand and finding no heartstrings on which to tug, baseball seemed doomed to be lumped in with the occultists and the elevator men, and now, no matter what Baker thought, it did face certain oblivion for the uncertain duration of a world war.

As for Eddie Ainsmith, the Nationals’ catcher and baseball’s erstwhile “test case” joined hundreds of his peers in the scramble to make new arrangements. The catcher found “work” at a Baltimore shipbuilder, where he would maybe play a little for the yard baseball team, which happened to need a catcher. This kind of arrangement would quickly become a flashpoint, with players and industry cozying up on one side while baseball’s leaders and the government tried in vain to ensure working players were actually working and not just playing in different uniforms.

News of Ainsmith’s case spread rapidly, including to the Cleveland/Philadelphia series getting underway in Philadelphia on July 19, the very same day Baker issued his decision.

When the Athletics won that rain-shortened 2-0 game, according to a tongue-in-cheek Philadelphia Inquirer account, the ruling had made its first mark on the season.

As Philadelphia batted in the first inning:

[Cleveland catcher] Steve O’Neill began to think up some useful job he could grab since Secretary Baker’s order for all ball players to work-or-fight, and he didn’t notice that Fred Coumbe was still out there pitching. The result was that while Steve was trying to decide between picking out knotholes in a shipyard and whittling down warts in a pickle factory, one of Coumbe’s pitches came along and went clear to the grandstand, and [the runner on third base] just naturally scampered over the plate.

The game recap ran alongside a separate article announcing that Johnson had declared the American League season would end on July 21. On what had become the season’s penultimate day, July 20, the Athletics and Indians would proceed with a double-header at Shibe.

But before the players shipped out, the fans in Philadelphia were determined to show just how “nonproductive” their national game could be.

In the conclusion, we finally tackle the forfeit, and sample a bit of the chaos that followed Baker’s decision.

In this period, the Washington American League team was nicknamed the “Nationals,” because history sometimes wants to make our work as difficult as possible. The team was more commonly referred to as the “Griffmen,” in honor of the manager/owner.

Ainsmith got his nickname from a Washington teammate, Doc Gesler, in or prior to 1915. Nobody knew what it meant then, either.

In reality, Ann went to live with her aunt and uncle, who proceeded to raise her. We don’t have all the facts, of course, but it’s safe to say that Ainsmith will not be featured in next year’s “Father’s Day” post.

In 1918, Landis was still perched on the bench of the Northern District of Illinois, preoccupied with whether or not he could get Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany indicted and extradited to Chicago to face his good justice over the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania (the State Department gently informed him he could not).

Is “Dorf” the best nickname ever? I want a nickname that nobody knows what it means too.

One of these men is not like the other! Baker! Ha! Looking forward to Part 3! I still maintain that Enoch Crowder is no fun, especially when teamed up with Baker. 😊

I read that one or another of the iterations of the Nationals gave birth to both the Minnesota Twins and the Texas Rangers. What a history the Nationals/Senators have had:

https://search.app/?link=https%3A%2F%2Fen%2Em%2Ewikipedia%2Eorg%2Fwiki%2FHistory%5Fof%5FWashington%2C%5FD%2EC%2E%2C%5Fprofessional%5Fbaseball&utm_source=igadl%2Cigatpdl%2Csh%2Fx%2Fgs%2Fm2%2F5