Arms and Armor - Part 3

The Brooklyn Dodgers donned protective helmets at the start of the 1941 season without knowing how well they worked. Thanks to Pete Reiser, they found out.

This is the third installment of a multipart series on the first major attempt to get major league batters to wear something to protect their heads. Here’s the story so far:

In Part 1 we covered a series of notorious 1940 beanings that pushed the National League toward action, resulting in an unsightly protective liner.

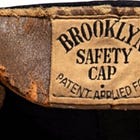

In Part 2 a far superior “armored cap” was invented by a motley crew of experts, organized by Brooklyn’s president, Larry MacPhail. The new cap’s spring debut was so successful MacPhail announced the Dodgers would make them mandatory during the regular season.

Here in Part 3, history’s unluckiest Dodger breaks in his Brooklyn safety cap.

In Part 1 we wrote a little about Roger Bresnahan, the early-20th-century catcher who pioneered several different pieces of safety equipment, including a hideous, inflatable batting helmet. For those in the 1940s in favor of head protection, Bresnahan’s example was frequently cited, and he became a kind of niche patron saint. In the tradition of such saints we assumed, naturally, that he was already dead.

But we forgot that 1941 was only a quarter-century after the old catcher retired from baseball.1 So alive was Roger Bresnahan in 1941 that the New York Daily News just called him up, on the telephone, to get his thoughts on the National League’s decision to try a helmet.

“It’s too bad you didn’t start sooner,” Bresnahan, 61, said of the campaign for head gear. “The average ballplayer would like to wear a helmet, but he shies away from ridicule. If he has the backing of the press it will stiffen his resolve to provide intelligent safeguards against skull fractures.”

But better late than never, he said. “There are a lot of reckless fireball pitchers around today who wind up and send that tomato whizzing in the general direction of home plate. You need protection against pitchers like that.”

The old catcher recalled his own beaning at the unwitting hands of a pitcher named Andy Coakley. “Knocked me unconscious.” Bresnahan was out so long that a Catholic priest in attendance helpfully performed last rites. After he recovered, “I then experimented with a crude sort of helmet. Coakley even helped me. But nobody in the newspapers took up the campaign and it died. There has been many a good man permanently injured, and one man killed, since that time.”

Still, the ubiquity of his once-ridiculed shin protectors gave him hope. “Ballplayers must learn things the hard way,” he said. “But they’ll learn.”

By early April, 1941, the Brooklyn Dodgers had come home, winging their way from their spring quarters in Havana to old New York, where they would open the 1941 season against their near neighbors, the Giants.

The Brooklyn safety caps came with them, and members of the New York sporting press were eager to see MacPhail’s latest passion project. The Dodger executive was like an old-time huckster going from town to town with a suitcase of gadgets, using theater to make a sale. With a group of national and local writers clustered around him (and no players within reach), MacPhail picked out a writer from the Chicago Daily News and stuffed a Brooklyn safety cap down onto his head. Once the helmet was in place MacPhail “clipped the unsuspecting writer with a stiff blow to the side of his head.”

“See how safe it is?” MacPhail said to the audience. The reporter rose, unsteadily, but retained enough of his higher functions to move to a spot out of range of MacPhail and any other demonstrations. Another satisfied customer.

On April 15, the Dodgers began their season at home. Some 31,000 Brooklyn fans saw history made, as the Dodgers became the first-ever team to use helmets in a regulation game, but no one was beaned and the home team lost. The safety cap did not see real action until April 20, during a game against the Giants at the Polo Grounds. 56,000 fans packed the park, eager to see a rematch of the opening series.

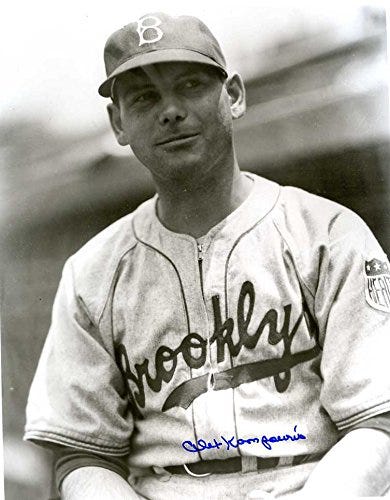

In the ninth inning the score was tied, 9-9. Brooklyn second baseman Alex Kampouris was wearing his helmet on first base. Catcher Mickey Owen hit a ground ball and the Giants threw to second to force Kampouris out and begin a double play. The throw arrived late and off-target, and it struck Kampouris on the side of the head, flush in the center of the left-side plastic panel in his cap. The ball ricocheted into center field, allowing a runner ahead of Kampouris to score the winning run. Not only had Kampouris’ helmet kept him safe, it had delivered the Dodgers a victory.

Leo Durocher was a highly regarded field leader, but the manager also had his flaws, including an awful tendency to hype promising young players by comparing them (favorably) to the game’s most transformational stars. He seems to have some awareness that this was a loaded way to offer praise, but that didn’t stop him.

“I know what [saying] ‘another Ty Cobb’ means,” Durocher said that summer. Nevertheless, he persisted. “But if there will ever be another Ty Cobb, his name will be Pete Reiser.”

Harold “Pete” Reiser was in his second season as a major leaguer. He arrived in Brooklyn in 1940 as a top prospect, and while he didn’t set the league on fire in his first partial season, neither did Ty Cobb. Durocher used Reiser frequently off the bench and liked what he saw. “He’s a little faster than Ty was at his best,” Durocher said. “I’ll take Reiser for speed against anyone in baseball, from either league. He has a fine arm, better than most. He sizes up the play in a flash and he starts in a flash.” And while it would take Reiser a minute to adjust to big league pitching, Durocher was convinced he would do it.

Even in the minors, Reiser had been prone to injuries, especially fluky ones, a trait which paired poorly with his max-effort style of play and eventually derailed his career. In 1939 he broke his own arm making a hard throw from the outfield and missed nearly all of the remainder of the minor-league season. Showing the tenacity Durocher admired, Reiser managed to come back for the last few games, using his non-dominant left hand to throw.

The Dodgers started the athletic Reiser at shortstop, but unfortunately for him, the team, and probably baseball altogether, the 1941 arrival of Reese created a logjam that pushed Reiser into the walled garden of center field. “I had Reiser at short,” Durocher said, “and we needed a good center fielder who could cover ground. I asked Pete if he could play the outfield. He told me, without any touch of bragging, ‘I can catch if you need me there.’”

On April 23, less than two weeks into the season, the Dodgers played the Philadelphia Phillies at Ebbets Field. Philadelphia started a pitcher named Ike Pearson and Reiser, batting third, singled off Pearson in the third inning and scored a run, bringing his batting average up to. 355. He had reached base in 22 of his first 37 trips to the plate, including three doubles, a triple, and a home run.

“He’s a natural hitter,” Durocher said. “He has no weakness that I’ve ever seen or that any pitcher has yet found. When he learns a little more through experience he may easily move into the .400 class.”

Some of Reiser’s teammates thought they might have spotted a weakness. In Cuba, they’d noticed that the ferocious Reiser had trouble bailing out from the barely controlled inside heaves that had become a staple of National League pitching. In the bottom of the third inning, Ike Pearson threw Reiser such a pitch. It was a sidearm fastball, meant to pass the hitter at chest-level, but it came in too high, and too far inside.

Reiser saw the danger and jerked his head back, away from the plate. But as the ball neared the plate, it “took off,” in the parlance of these dangerous times, seeming to swerve a further eight to 10 inches inward, through the spot where Reiser had pulled his head. It was the first serious beaning of the new season. Fittingly, the honor went to a Dodger.

“There was a sound like a rifle report,” one paper recounted. Reiser fell flat on his back. Stunned stiff, his knees remained locked in a batter’s crouch. The crowd “wailed a long, fearful ‘OOOOH’ then fell silent.”

Watching from his box seat, MacPhail thought it was the moment of truth. Either Pete Reiser would rise, triumphantly tossing away a shattered piece of plastic that had saved his life, or that plastic had failed and he would never rise again.

Reality was, as always, murkier. Pearson’s duster appeared to have struck Reiser on the cheekbone, a few inches below his temple. His teammate, first baseman Dolph Camilli, recalled standing over Reiser and seeing incontrovertible evidence. “You could plainly see the imprint of three stitches where it hit him.”

Reiser woke up before the stretcher came, but he was badly dazed, and MacPhail followed his standard procedures, ordering an ambulance to take the player to “Little Ebbetts Field,” otherwise known as Caledonian Hospital.

At the hospital Reiser was conscious but groggy. “I don’t know just what happened,” he said. “I saw the ball come up to me and I pulled back. I don’t know whether I lost it or whether it sailed.”

The lack of a causal factor made things worse. “If Reiser could get beaned, anybody could get beaned,” one commentator wrote. “He’s a quick, alert youngster who told us himself he’d had plenty of practice outguessing fastballs.”

A detailed medical exam revealed that Pearson’s errant pitch made partial contact with the right plastic panel of Reiser’s safety cap, absorbing as much as half of the shock of impact. Part of the evidence of this was the imprint of the cap’s inner zipper on Reiser’s face. It wasn’t the triumphant moment MacPhail imagined, but the result was ultimately the same.

“He’s a very lucky man,” one of the attending doctors reported. “He certainly would have had a fractured skull if it weren’t for the helmet which absorbed part of the shock.”

The player’s entire head throbbed, his cheek turned purple, but no bones were broken (for Reiser this was near to a miracle), and he would return from the injury free from the dizzy spells and double vision that had plagued other unprotected beaning victims.

The center fielder’s injury “drove another rivet into the argument that all batters should be protected by some form of head bumper,” the Cincinnati Enquirer said. But the speed of his recovery might have been even more compelling to his fellow players. Three days after the beaning, a smiling Reiser was photographed sitting up in his hospital bed, reaching for a radio to turn on the Dodgers’ game. On April 27 he was released from the hospital, and on April 28 he was back in uniform. Unlike his fellow “rivets”—Cochrane, Reese, Jurges, et al.—Reiser only missed a week and a half.

“I didn’t want to [wear a helmet],” Billy Herman said. Herman, a second baseman, arrived on May 7 following a trade with the Chicago Cubs. “[I had] a stupid attitude. You didn’t want to give the pitcher the satisfaction of knowing you were covering up your head.” MacPhail smiled, shook his hand, and handed Herman his standard-issue Dodger head protector. “But I wore one after he made us.”

The safety cap was still a work in progress, and MacPhail was unwilling to stop tinkering until players ceased complaining. There were some complaints. The plastic panels were initially too flat and stuck out away from the head. Some players felt it was still too heavy and hotter than a normal cap.

The plastics people refined the shape of their mold and reduced the thickness of the plastic, and other models tested a lighter panel made with hardened fabric. The zipper was eliminated when it became clear the panels fit better when they were sewn in place in their proper location (the zipper smooshed onto Pete Reiser’s face may have also been a consideration). By early May the Dodgers debuted what they claimed was version 25.0, and this time the players could find “very little if any fault.” Like Herman, had also come to realize that MacPhail had been right.

“Every Dodger is wearing [a safety cap] and there isn’t a complaint,” MacPhail said. “I am convinced that we are on the right track at last.”

With a recovered Reiser and a “perfected” cap now in production, the safety train finally started rolling. On April 26 the Washington Nationals became the first American League team to utilize Brooklyn safety caps. “Most of the players in the starting lineup wore the helmets,” while several others reportedly preferred to “break them in” (pun probably not intended) before wearing them during a game.

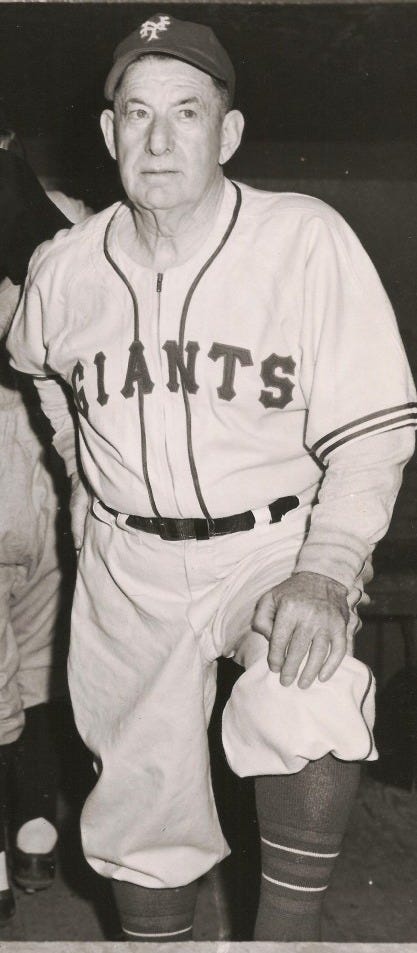

Reiser’s beaning may have done the most to spur the rival Giants to put in an order of their own. Giants shortstop Billy Jurges could not have been happier. The third of the Famously Brained of 1940, he had suffered through the offseason experiencing hearing loss and recurrent dizzy spells. Like many other players who endured difficult recoveries, Jurges had been converted to the cause, pushing Giants manager Bill Terry to pick up a phone and find some helmets, even if he had to call Brooklyn. “One more crack on the noodle,” he warned, “and they’ll be pushing me around here in a wheelchair.”

Players were buying in. This was the climactic moment in MacPhail’s crusade, and while the executive took no small amount of satisfaction from the flowers he was getting in the papers, the cap’s popular breakthrough begged an unresolved question:

Who actually owned the rights to the Brooklyn Safety Cap (patent pending)?

And, relatedly, how rich was their creation going to make them?

As an early holiday gift for our readers, we’re going semi-weekly for this story, with installments releasing on Mondays AND Thursdays.

On December 18: “Hey everybody, look, it’s capitalism!”

Over on Clear the Field…

If you need a break from the multi-part madness, Ted and I just posted a new podcast episode exploring our favorite musical baseball rebellion. Listen here or wherever you follow the show (you do follow the show, right?)

Put another way: Roger Bresnahan is to 1941 as Wade Boggs is to 2025.

The new product should have been branded the “Noodle Crack Preventor,” with royalties flowing to Billy Jurges - truly a missed marketing opportunity.

Paul, I was convinced that Reiser would be a goner; glad to know an earlier iteration of the batting helmet worked in his case. I will ‘stay tuned’ for part 4 on Thursday!