Arms and Armor - Part 4

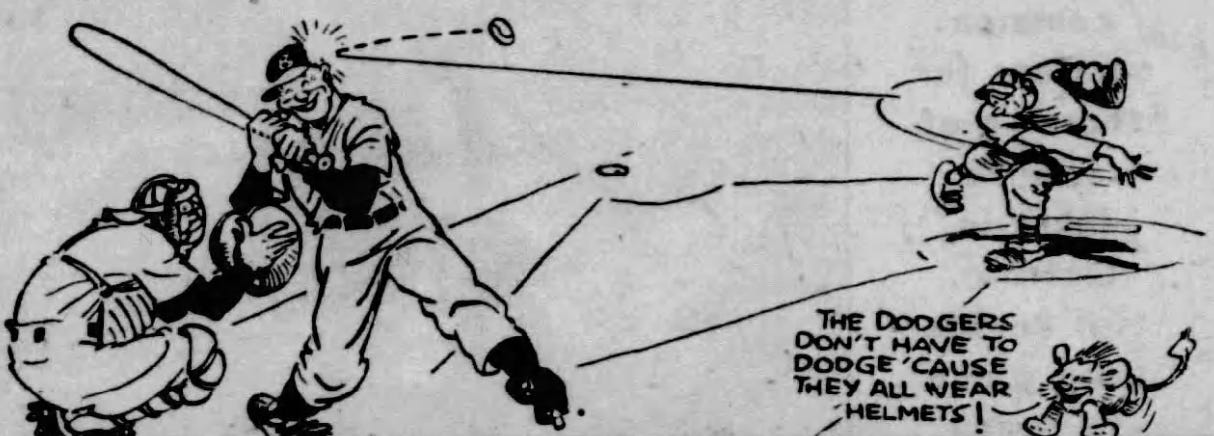

A dispute over the rights to the first modern batting helmet was obscured by a summer of beanball violence in the major leagues.

This is the fourth (!) installment of a multipart series on the first major attempt to get major league batters to wear something to protect their heads. Here’s the story so far:

In Part 1 we covered a series of notorious 1940 beanings that pushed the National League toward action, resulting in an unsightly protective liner.

In Part 2 a far superior “armored cap” was invented by a motley crew of experts organized by Brooklyn’s president, Larry MacPhail, who made it mandatory for all players in the Dodgers’ system.

In Part 3, history’s unluckiest Dodger, Pete Reiser, used his head to show the new head gear was both safe and inconspicuous.

Here in Part 4, intellectual property battles flare and National League pitchers get even wilder.

On March 4, 1941, four days before the Brooklyn safety cap debuted in Havana, an inventor in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania made local news by debuting his own protective head gear featuring a very different material: cork.

Mr. C.J. Estel (we don’t know what it was with the two-initial moniker in this period) assembled a cloth cap from tubular sections, and each section was filled with finely granulated cork. The plan was to hide the structure under an outer cloth layer and make it resemble a “normal” cap. Estel’s design was ahead of its time in that it even had an adjustable ear flap of sorts. Even better, there would be no supply chain problems. Estel wouldn’t need to call up DuPont to help fill his orders; he worked in a cork factory, giving him access to all the soft spongey material he needed.

“Cork is a fine insulator,” Estel told a curious reporter from the Pittsburgh Press. “It’s light, resilient, and has remarkable shock-absorbing powers.”

He described himself as a rabid baseball fan with a “knack for tinkering,” and he’d decided to tinker his way into a solution for the game’s most pernicious problem, though he was careful not to overpromise.

What we don’t know about the cap yet is the extent of the protection it will give. I know it will prevent a skull fracture and the most severe concussions, but I can’t say if it will prevent a man from being knocked out. After all, a pitcher’s fastball deals a pretty tough jolt.

The inventor said he was going to have some sample caps made up and planned to send them to various spring training camps looking for what amounted to a cold read. “If some player will just get a few hits while wearing the cap, I think the battle is won.”

Estel was careful to give due credit. “I’m not the sole inventor,” he said. “A friend of mine, R.M. Waibel, has as much in the cap as I have. And my wife is a co-inventor, too. She’s handy with a needle and sewing machine, and we might have had a lot of trouble assembling things if it hadn’t been for her help.”

The Estel-Waibel-Estel or EWE cap, (pronounced “Ewww”) might have worked brilliantly, but as anyone who has tangled with the United States Patent Office knows, a successful idea does not ensure a successful product. Timing is everything, and the cork cap, arriving in between two separate MLB-sanctioned products, had missed the market.

In late April, 1941, the market for Larry MacPhail’s “Brooklyn safety cap” was picking up. The New York Giants, inspired by Pete Reiser’s near-death experience, were making inquiries; the Washington Senators were already wearing theirs; and a line of interested clubs was forming. When the Giants got their caps in early June, Frankie Frisch, the manager of the visiting Pirates, tried one and was pleased with the experience, saying he “hoped the manufacturers would hurry up and deliver ours.”

The Giants’ shopping experience demonstrated that the safety cap (with every unit marked “patent pending”) remained a grey market, not available unless you knew who to ask. The Giants’ manager, Bill Terry, reportedly had to go directly to MacPhail for “permission to copy the Dodger style” of cap. This caused some friction (and delay), with Terry stating he’d “sooner go up there bareheaded” than beg Larry MacPhail for anything. A member of the Giants’ front office intervened to smooth things over and close the deal.

The question of just who owned the rights to the safety cap would take years to settle, but when he debuted it on March 8, MacPhail seemed happy to assign that credit to his collaborators, saying “it was designed jointly by Dr. Walter Dandy, outstanding brain specialist, and Dr. George Bennett, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.”

MacPhail added that “a patent already has been applied for, although neither of these two gentlemen was or is interested in making any money out of it,” suggesting he and the good doctors might have had different financial goals for their project. There is no question that MacPhail was driven by a sincere desire to make the game safer for the players. But, unlike the doctors, he seemed just fine making a few dollars in the process.

Or maybe more than a few. In late March, without calling out the Brooklyn safety cap or MacPhail by name, the Philadelphia Athletics owner, Connie Mack, predicted that “the man who invents a helmet that insures absolute protection will make a fortune…the time is coming when they will be standard equipment.”

And not just in the majors. What became standard there would flow down through the minors, semi-pro clubs, company teams, and even little league. In early May, as the safety cap began drawing interest from other teams, MacPhail and “co-inventors” Dandy and Bennett put out a statement assuring the public “they would peg the price low” on the caps. In doing so, it was their hope “to furnish caps to players on the sandlots and small minor leagues at a very nominal cost.”

In economics, this is known as “penetration pricing,” a strategy for flooding the market before any competitors can find their footing. This was not exactly what Walter Dandy had in mind.

In a posthumous biography on the neurosurgeon, historian William Lloyd Fox cited correspondence found in Dandy’s papers showing that his discussions with MacPhail on the future of the safety cap been far more acrimonious behind closed doors.

“I had planned to take out a patent on it in my name,” Dandy wrote in May, 1941, “and turn it over to the major leagues with no financial return except the cost of the procedure.” He complained that MacPhail had called him early on to say he would be glad to “take the patent out in [Dandy’s] name,” an offer a patent lawyer later informed the doctor was akin to somebody offering to take your money and keep it safe—in their own account.

The neurosurgeon became convinced that the Dodger president had been scheming to take a controlling interest in the safety cap and profit off of it. The dispute got bad enough that Dandy wrote not only Ford Frick, the National League president, but also the commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, to complain. Seeking intervention from a higher power, Dandy told Frick:

I still am not interested in any financial return, but I think I have been played a dirty trick. All I want is credit for helping baseball, and I surely expected this degree of gratitude in return for my efforts.

Dandy misunderstood the relationship between the individual clubs and baseball’s central administration. He seems to have assumed Frick and Landis were MacPhail’s superiors, when, in effect, the opposite was true. Both men essentially gave Dandy the same response: This is between you and Larry.

The label “Beanball Wars” doesn’t seem to have been regularly applied at the time, but a Cleveland writer named Gordon Cobbledick used it once, in July, to describe what was going on:

It is no secret that a sort of bean ball war is raging over there [in the NL], and this may explain why the leading hitter of that league boasts an average which would scarcely place him among the first 10 in the American.

And the hits just kept coming. May was relatively quiet, but in June and July batters began dropping like flies.

Roy Weatherly, Cleveland, June 11

On June 11, Roy Weatherly, Cleveland’s center fielder, was struck above the right temple—the pitcher that hit him said his aim had been thrown off by a blister on his middle finger. Roy and Mrs. Weatherly got their picture taken at the hospital but he avoided serious injury. Five days after the incident the Indians procured 16 safety caps, eight for home and eight for the road. Given the limited inventory the team trainer would manage the caps in the dugout and hand them out for batters based on their head size, trading head injuries for head lice. Yuck.

The Clevelanders first wore the caps on June 26 and Weatherly was among the half-dozen test subjects, who collectively reported the added weight of a safety cap was no bother.

Hank Leiber, Chicago, June 24

Hank Leiber had a famously hard head. The outfielder had been beaned by Bob Feller, perhaps the hardest-throwing pitcher in the majors, during spring training in 1937. Leiber missed half the year but battled through dizzy spells to return and boost the pennant-winning Giants.

On June 24, Leiber, now with the Chicago Cubs, was hit on the back of the head by a former Giants teammate, Cliff Melton. Melton somehow did what Bob Feller could not, knocking Leiber out for the rest of the season.

Mickey Owen, Brooklyn, June 30

The safety-capped Dodgers remained on the firing line. On June 30 Brooklyn catcher Mickey Owen was leveled in an incident that showed the limits of cutting-edge protection. A fastball caught Owen over the left eye. He lay unconscious for five minutes while blood dripped into the dirt, his safety cap laying forgotten nearby.

“Hard-bitten umpires, players and writers blanched at the sickening sight,” but it looked much worse than it was. The injury had reopened an old scar he’d gotten earlier in his career when accidentally clipped by a bat. Owen got six stitches and the Dodgers got another punch in their Caledonian Hospital Club card—their next set of X-rays would be free.

“It wasn’t the kid’s fault,” Owen said, sitting up in his bed with his left eye swollen shut. “I pulled away, but the ball just kept swerving in.” His luck in that moment depended on your perspective. A half inch higher and the pitch would have bounced off his protective plating. A half inch to the left and he might have died.

Owen had recently been named the starting catcher for the National League All-Star team, but the doctor’s order of five days’ recuperation for his “mild concussion” threatened to keep him out of the July 8 contest. Owen vowed to “try mighty hard” to make it to his first All-Star appearance. He made it, taking one at-bat and flying out to left.

Jeff Heath, Cleveland, July 23

The now-helmeted Indians had better luck on July 23, when their best hitter, outfielder Jeff Heath, was beaned at Yankee Stadium. The ball rattled off Heath’s protective cap, bouncing an estimated 30 feet. He was “shaken up a bit,” understandably, but suffered no ill effects and stayed in the game.

Bill Dickey, New York, July 24

The very next day the tables were turned, and one of the Yankees’ best hitters, catcher Bill Dickey, was hit on the right side of the head. The Yankees’ players had scorned the movement toward protection so there was nothing but some pinstriped cloth between Dickey and the rogue fastball that caught him. He was able to walk off the field. “I had it worse in Detroit a few years ago,” he said. “The whole ballpark was spinning that day. I didn’t lose consciousness or black out at all today.” So call it a draw.

In the clubhouse Dickey showed how the Greatest Generation did it, drinking a soda, smoking a cigarette, and taking a quick shower before heading to the hospital. “It struck me two inches above the right ear,” he said. A reporter with an agenda asked him if that spot would have been protected under a helmet. “Yes, I believe so,” he said. Precautionary X-rays were negative. A month later nearly all Yankees, including Dickey, were reported to be using safety caps.

Frank McCormick, Cincinnati, July 23

The Cincinnati Reds had purchased safety caps and they were in the dugout on July 23 at Crosley Field, but first baseman Frank McCormick sheepishly admitted neither he nor any other Red had used one. McCormick came to regret that decision in the fifth inning when he was hit in the head by a Dodger pitcher, Kirby Higbe. He never lost consciousness but suffered the inevitable “mild concussion.” “I had to get hit in the head to take my first ride in an ambulance,” he said, smiling as his stretcher was lifted into the car.

Two days later McCormick was back on the field, now wearing a safety cap. Several of his wiser teammates joined him.

Save for the Yankees and Indians, the 1941 beanings continued to fall on National League hitters. Players marveled at the disparity. The Red Sox’ Ted Williams was wrecking AL pitchers that summer, on his way to a .406 batting average. Brooklyn pitcher Whitlow Wyatt said it would never have happened in the National League—NL pitchers would have dusted Williams off until he gleamed. “If that fellow was over here, he would have to do most of his hitting from a sitting position.”

Cobbledick, the Cleveland writer, acknowledged the immorality of the beanball but explained that many baseball people saw it as a “legitimate weapon.” And even those who didn’t see it that way still had to use it:

They are compelled to adopt an attitude akin to that of the soldier, who admits that war is hell but knows that the only way to stop an army of aggression is to fight it with another army. The soldier knows that war, in the end, is a profitless undertaking for all concerned, but he also knows that defeat and subjugation is likewise profitless.

The writer concluded his missive on the Beanball Wars by advocating for the baseball equivalent of mutually assured destruction: “The only loser in such a war is the team which allows its opponents persistently to dust off its batters without retaliating.”

To that end, Cobbledick advised the Indians’ pitchers to do more dusting of their own down the stretch.

As an early holiday gift for our readers, we’re going semi-weekly for this story, with installments releasing on Mondays AND Thursdays. The final installment will be released on Monday.

In spring training, Larry MacPhail had declared, “Mark my words—every club in the majors will be wearing helmets before the season is over.”

After helmets save one season and doom another, we’ll see if Larry was right.

On December 22: “Helmeted Ever After”

Gordon Cobbledick? Really? This is why pseudonyms exist. Don’t be afraid to use them, people.

Great, it’s a five-parter! Talk about in-depth reporting; where did you get all of the photos of the featured players wearing the Brooklyn Safety Caps?! 🧢 (Still lol about the EWE cap; not sure about how crumbled cork would stop the impact of a baseball!) ⚾️