Baseball’s Flirtation with Democracy

In one of the great promotional stunts of all time, 1,115 people managed the St. Louis Browns…and it went pretty well!

On August 15, 1951, a quarter-sheet “newsvertisement” ran in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, featuring an illustration of the manager of the American League St. Louis Browns, Zack Taylor, seated in a rocking chair, confronting a horde of second-guessing fans:

Thus did the Browns announce “Grandstand Managers Night.”

The idea came from the fertile mind of the team’s new principal owner, Bill Veeck, who had purchased control of the team on July 3. Veeck was determined to make a splash in moribund St. Louis, and several of his promotional Great Works were created that summer, including the infamous moment when he inserted a person with dwarfism, Eddie Gaedel, in the Browns lineup.

The ad for Grandstand Managers Night included a blank lineup card for fans to fill out and submit, along with a brief letter explaining how they would manage a team if they were in charge. Though the ad promised to run “for the next several days,” it only ran that once, because, according to Veeck, a horrified editor at the Globe-Democrat “found it and killed it.” The suddenly one-and-done ad elicited 1,300 applications to join what Veeck called, “our great experiment.”

Veeck picked his two favorite letters and signed the writers (both men; though many women responded) to one-day contracts to act as coaches for the Browns, with on-field roles, uniforms, the works. He duly submitted the documentation to the American League office for approval, but Will Harridge, the AL president, called Veeck to tell him he wouldn’t approve any stunt contracts—and that anyone without a real contract had better stay off the field at Sportsman’s Park. Veeck pivoted, awarding each winner a 2-foot trophy inscribed: “One of the best coaches ever banned from the coaching lines.”

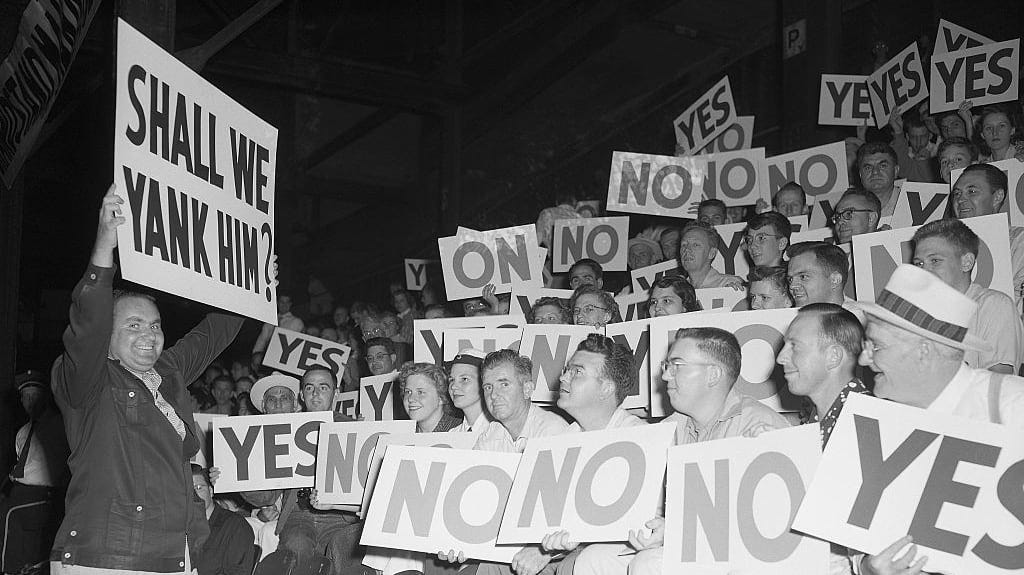

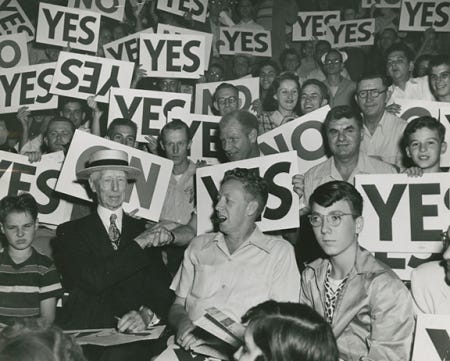

On August 24, some 1,115 entrants showed up for the game and took their seats in a specially-reserved section behind third base. Each was issued a two-sided “YES/NO” placard, and a team staffer had a stack of questions related to managerial strategy:

Put him on?

Sacrifice?

Steal?

Pitch to one more?

Pinch hitter?

Infield back?

Infield in?

The first draft of the placard calling for a pitching change—photographed in Veeck’s office—read, “Shall we jerk the bum?”, but a milder version was used in-game. A local circuit judge had been retained to tabulate the votes in real time, and his results were conveyed to the Browns dugout via walkie-talkie.

As promised, incumbent manager Zack Taylor sat in civilian clothes, smoking a pipe on top of the Browns dugout until umpire Bill Summers chased him off the roof and told him personnel out of uniform must sit in the stands. Taylor obligingly dragged his rocking chair to the owner’s box nearby and joined the honorary coaches seated there (in uniform).

One of the coaches, Clark Mitzie, a high school music teacher, was asked if he was disappointed he couldn’t work on the field during the game.

“Have a hard enough time living this down anyway,” Mitzie said.

The Browns’ opponent on August 24 was the Philadelphia A’s. The game pitted 7th place versus last place in the American League, ensuring the outcome could do no real harm.

Still, Philadelphia’s leadership had mixed feelings about being involved. Their general manager called the event “a travesty,” and their manager, Jimmy Dykes, threatened to call for a forfeit if the decision-making process slowed down the game. On the other hand, the great Connie Mack, just retired from active management but still traveling with the Athletics (he owned the team), spent several innings with Veeck in the “GMs” section.

“I always tried to get the Philadelphia A’s in on something,” when promoting, Veeck wrote in his autobiography. “Mr. Mack was a boyhood idol of mine.”

As Mack was “the personification of dignity in his old-fashioned high-collar shirts and his precise and rigid bearing,” it brought Veeck no small amount of joy to see the great man in the thick of one of his schemes. Mack was a real supporter of the Browns’ owner—though he did say the Gaedel signing had been “a little too far.”

Once the game began, the system was tested almost immediately. The Browns’ starter, Ned Garver, was knocked around by the A’s hitters, and left fielder Gus Zernial plated three with a home run. The GMs were asked if a new pitcher should be brought in. Veeck—seated with the GMs—voted to pull him, as did Mack, but Veeck’s wife, Mary Frances, joined the majority who wanted to give Garver another chance.

Two more men reached base, and with runners at first and third, the GMs were asked if they should move the infield in, but they declined, keeping the defense in position to make a double play, and Garver delivered just that, ending the inning.

From there, Ned Garver was a different pitcher. Only one Philadelphia player subsequently reached second base, and Garver finished the complete game by retiring the last seven batters he faced.

By majority vote, the GMs had made two key changes to the usual lineup, inserting first baseman Hank Arft and catcher Sherm Lollar. Lollar had three hits, including a double and a home run, driving in two. Arft also drove in a run. The GMs made just three in-game offensive decisions, all regarding steal attempts, and the one time they voted to send the runner, he was predictably thrown out. That the system functioned at all without ever giving Dykes sufficient cause to protest speaks to its pre-planned intricacy.

Under democratic rule, the Browns won, 5-3.

After the game, a massive fireworks display was set off beyond the outfield walls. “Thanks, grandstand managers, for a swell job.” Given the Browns’ win, that was to be the end of the message, but the fireworks crew accidentally also set off the message to have followed a loss: “Zack manages tomorrow.”

The game attendance was barely 4,000, a disappointment given how much effort had been put into the promotion. But not all masterpieces are appreciated in their time, and democracy doesn’t work in every context, as the victorious Ned Garver observed afterward. “That homer of Sherm Lollar’s in the third,” Garver said, “didn’t come out of any poll.”

Back under authoritarian rule, the woebegone Browns lost eight of their next nine games.

Looking for another good story? We have some recommendations: