Sources and Errors (and a Meta-Piece on the 1980 World Series!)

Sources

“No sport gets as much mileage out of reminiscence as baseball,” New York Times sportswriter Leonard Koppett observed in 1969, right before launching into a Spring Training conversation with Richie Ashburn and Gil Hodges that put a few more turns on the odometer.

Another New York-based writer, Jimmy Breslin loved this about baseball, a sport “where stories of the past are most important.” Stories of the past were as prolific as they were enjoyable, and the sport’s slow, broken-up pace at least offered plenty of quiet moments in which to share them. But they were not to be entirely trusted, he cautioned his readers: “Most legends should be regarded with suspicion.”

Still, he wrote, “if one is to have any fun in life, one should proceed with the understanding that reminiscences are to be enjoyed, not authenticated.”

This, in total, is a good encapsulation of our mindset here at Project 3.18. This newsletter aims to do two things:

Build a fact-based archive of baseball’s lore—its stories and traditions

Peer through the window these stories offer into their day and times and appreciate what we see there

We promise to approach our research with suspicion and diligence. We’ll treat our material with suspicion so you don’t necessarily have to. Project 3.18 aims to be a work of historical nonfiction. If a juicy tidbit reaches your eyes here, that means we are confident it is factual. The details of the stories we tell here will have a sourced basis, with a heavy preference for established secondary sources such as newspapers and published books, and, if all goes well here, primary source accounts. Any quotes attributed to an individual will always have a source behind them.

As we build a community here, we want to add narrative contributions from readers to this body of work. When reader submissions are included in Project 3.18 pieces, that work will be credited to them or kept anonymous as per their wishes. If it’s not clear what those wishes are, contributions will be kept anonymous.

Project 3.18 retains source information for all of our work. Generally, we won’t share this in the stories themselves unless we are drawing extensively on someone else’s work (numerous excerpts, etc.)

If you would ever like to know where a particular fact or piece of information came from, or generally what sources were used in preparing a piece, don’t hesitate to email project318@substack.com and ask. We’ll be happy to show our math.

A Word on…

Wikipedia—Project 3.18 will only draw on Wikipedia for the most basic or broadest pieces of information. For example, on what day did Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak end? I don’t know off the top of my head. Let me go check Wikipedia. Ah, okay, it was July 16, 1941. This is how I function.

Quotes or very specific pieces of information won’t be derived from Wikipedia (even if they are present there). Event details and commentary won’t come from Wikipedia (even if similar information is present there). If all I have to tell you about a story is what you can find on a Wikipedia entry, or even what you can find on the digitally-accessible sources a Wikipedia entry cites, that story is nowhere near ready for prime time, and it won’t see daylight here. Project 3.18 pieces will always have multiple sources behind them, with Wikipedia only contributing as described above.

Statistics—Statistics are essential to sports stories and baseball stories, but some matter much more than others. We’ll pay attention to those. Let’s say, for example, a catcher hits a home run in Game Seven of the World Series. Does he hit home runs all the time? Is that what he’s there to do, hit bombs for his team? That’s one story. But what if he’s a poor hitter, defensive-specialist type? Maybe he’s only in the game because he’s the pitcher’s preferred guy, and maybe he hasn’t hit a home run in months. That guy hits a home run in a Game Seven, and then retires? It’s a completely different story, one worthy of a slickly-produced retrospective.

At the end of the day, though, Project 3.18 is a historical project, not an analytical one, and stat-heads will find it wanting in that regard. We will use statistics sparingly, simply, and even loosely, to the point of rounding batting averages and earned run averages, e.g. a 2.97 earned run average might be given as “an ERA under three.” When we do cite a statistic, we’ll take the usual care to make sure it is right—statistics and precise game details will come from baseball-reference.com or retrosheet.org unless otherwise noted.

Links—As I do in this piece, I’ll sometimes share a link to make it as easy as possible for you to access additional content I found enjoyable and informative (you’re welcome). When I post a such a link, the link was working at the time the newsletter went out. As we all know, things change on the internet, and I can’t promise that a link will live forever or work wherever. If I am extremely concerned that a link have a long life, I won’t include it. I won’t include links to any type of paywalled content, but you may feel free to do so in Comments if you are trying to highlight an additional resource for whatever we are talking about (thank you!)

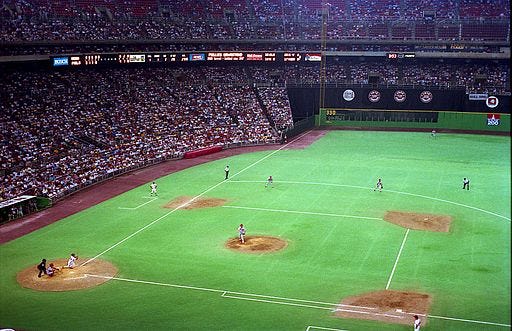

Photographs—All photographs published here at Project 3.18 are intended to be shared in a manner consistent with any relevant terms of use, including any required credit, which will be included in the photograph’s caption. Sometimes that won’t be pretty but I’m new to these rules and trying to follow them.

If you have relevant photographs (and the rights to them) of an event we cover here at Project 3.18 and would like to share them with us, that would be absolutely amazing.

Errors

Here at Project 3.18, we foresee three big classes of errors (we’ll come back and add other types as they are discovered):

Typos: I am sorry if I miss a double “the” in the editing process or give Rick’s name as “Rich.” It’s going to happen, no matter how careful I try to be (very). If you spot such a typo, email project318@substack.com, and I will fix it. Please don’t use comments to identify typos.

Brain Farts: There will be mistake/brain-fart/whoopsie errors, and I really hope you’ll be kind to me on those, because I’ll be embarrassed enough just knowing it’s happened. Once I got three drafts through a piece while all the while giving Joe DiMaggio credit for only a “52-game” hitting streak. I know it was actually 56 games, but for some reason I wrote 52 and it took far too long for my brain to catch that this had happened. No one ever saw the mistake, but I was still mortified. If (and when) you spot an error like that, brilliant people that you are, you can note it in a comment, though I do hope you’ll be nice about it.

The other kind of error you’ll find here at Project 3.18 may or may not be an error at all. When we are dealing with past events, the details tend to drift a little bit the more cycles of reminiscence and recording they’ve been put through, like a game of Telephone. And I have a perfect example for you. It’s a bonus post here in the disclaimer page! You’re so surprised and thrilled, I hope you’ll consider subscribing, if you have not yet done so.

Whose Ball Was It, Bob?

During the final inning of Game Six of the 1980 World Series, Bob Boone, the Philadelphia Phillies’ catcher, tried to make a catch in foul territory. I encourage you to watch the moment yourself because we have that privilege. The at-bat we’re about to dissect can be found at the 2-hour-and-45-minute mark. The Kansas City Royals’ third baseman, Frank White1, popped up weakly on the first base side, near the Royals’ dugout. Boone ran over to make the play and appeared to do so as the ball dropped into his glove…only to jump right back out. Fortunately for Boone and Philadelphia, the Phillies’ first baseman, Pete Rose, had charged in to back Boone up on the play, and was so thorough in doing so that he was standing literally right next to Boone when the ball escaped the catcher’s glove. Rose was able to snag the ball out of the air around his knees and in doing so send half of Pennsylvania off in search of a fresh pair of underwear. It is one of my favorite baseball moments.

So that’s how the 26th out happened, but the question of why it happened the way it did is where things get interesting. Let me show you three different quotes from Bob Boone, recalling the play.

Here is what Boone told Bryant Gumbel, locker room correspondent, immediately after the game. This is mere minutes after it happened:

“It was Pete’s ball, but I didn’t see him and didn’t hear him. I was listening for him to call me off, but who could hear anything out there? So I just stuck my gold glove out there and the ball clanked off.”

This seems like Boone is saying he bit off more than he could chew going after that pop-up, and that he was the one backing up Rose.

Fast forward to 2016. In his book, Champions of Philadelphia, Rich Wescott quotes Boone thusly on the same play:

“As a catcher, it was my territory. When I got over there, I thought, Where’s Pete? He’s not there. Then he came flying down, and I thought he’d knock us both into the dugout. At that moment, I wanted to kill him. Then after he caught the ball, I wanted to kiss him.”

This reads as a contradiction. First it was Pete’s ball, now it’s Boone’s territory. But then he’s looking for Pete? In his territory? Why?

Now let’s listen to what Boone said in 2019, during an interview with Lew Freedman, the author of Phillies 1980! (exclamation point his). “Did Rose [tell you] how he screwed up the pop-up?” Boone asked the author.

“It should have been his ball all the way. He’s heard it from me many times. I knew we were both going into the dugout. I am the one who hustles down the line.”

Okay, so here Boone seems to be saying that Rose, of all people, didn’t hustle(!) as he should have for the ball, forcing Boone to try and make the catch. I can’t comfortably lump this in with either of the two prior accounts, though it does seem like the longer Boone has to think about this moment, the more culpable Rose is in it.

Between all of this, how am I supposed to tell you what happened, concisely and convincingly? I can’t put all this in. Well, I’ll give you my informed version, and at least we have a place to start. Maybe you agree, maybe you have a completely different source from 1996 or something and that’s what you go with, and it’s an interesting bit of historical exchange we can have. Or, maybe yours is indeed the missing piece, an affidavit signed by Bob Boone, perhaps, that will settle the matter once and for all. I will be glad to add it to the puzzle we’re putting together here and give you the credit. Such moments are what Project 3.18 is designed to do.

In any event, an out is an out, one of 27. Why am I obsessed with this one? It’s because this one was a fifteen-second melodrama that hit the crowd like a thunderbolt. It has great characters and lots of moving parts to fiddle with in an exploration of how something so routine became so unexpectedly thrilling.

Anyway, here’s what I think happened:

If it wasn’t Boone’s play from the start, he made it his play by taking evident control of things very quickly. His body language was decisive and it said: “My ball.” Rose saw the message and assumed the “back up” role.

The play became what it did because Rose, all-in player that he was, ran into the catcher’s peripheral vision so enthusiastically that he distracted him. The surprise appearance of a barreling Pete Rose mere inches away from both himself and the yawning Royals’ dugout forced Boone to take the briefest but costliest of glances in Rose’s direction. This took his eye away from the ball at a crucial second, when the ball is literally arriving in his mitt, and this momentary glance led to the accidental catch-and-release, which gave Rose the opportunity to be a hero for defusing a bomb that he himself had accidentally lit.

To justify my account, I point to Boone’s almost sarcastic Gold Glove reference in 1980. I read it as a coded way of saying he could have made the catch just fine if Pete hadn’t shown up and distracted him. By 2016, he no longer says it was “Pete’s ball,” and that it actually happened in his area of responsibility, and which aligns with the footage. He never looks to Rose until that fateful last second. And he also states his concern that he and Rose would collide and fall into the dugout–he was distracted by this (reasonable) apprehension, which Rose prompted by running in too close.

And the 2019 version, I kind of leave it mostly off to the side. Maybe you can square it if you say that Boone charged as he did because right after White fouled it off, he looked down towards Rose and decided that, since Pete Rose wasn’t hustling(!), he would have to take over and he did the best he could from there.

Should the most immediate account be given primacy? Not necessarily. Context matters, and in some cases it prevents an easy judgment. Certainly, the incident was fresh in his mind when Boone talked to Gumbel in the Phillies’ locker room, but keep in mind, he’s also in the exultant shock of winning a world championship and with his teammate Rose likely in earshot.

With respect to the Boone/Rose Mess-around of Game Six, perhaps the best-case scenario is that this write-up will somehow make it back to Mr. Boone and we can connect and work together to settle these disparate accounts. In that case, I will be altogether delighted if my working account is proved wrong.

Ultimately, Project 3.18 isn’t going to do this level of historical-sausage-making in our narrative pieces. We’ll tell straightforward accounts that synthesize all the information we have. Here, as we talk about sources and accuracy, I just wanted to give you a sense of how difficult that work can be.

Optional obsessive parsing will always be welcomed in the comments of our stories, for all who are interested, but, again, be nice.

I know that Frank White was the second baseman for the 1980 Kansas City Royals, not the third baseman as written above. That was a test, as well as an example of a Class 2-type error. If you passed this test, wow, have you found the right newsletter—if you haven’t subscribed yet, you really should do so.

And if you didn’t pass, actually, you still passed, because Project 3.18 is not baseball-reference.com and whether White played second or third is not relevant to what is, either way, an excellent story we’ll tell here in full one day. Still, we’ll always do our best to get these details right.