Playing Hurt - Part 2 of 2

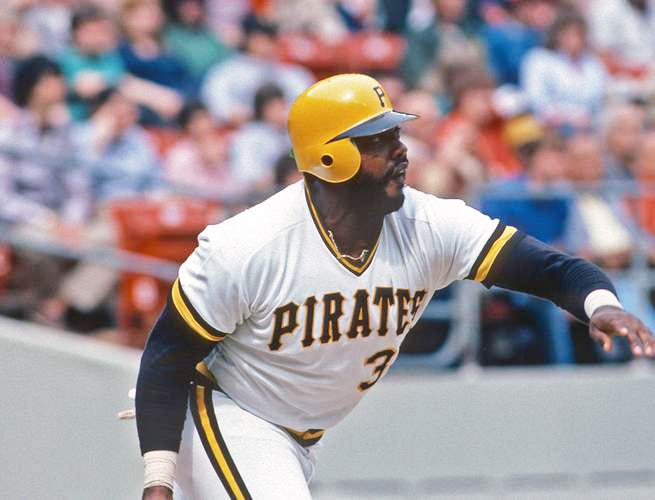

Dave Parker’s 1980 trade demand showed that a million-dollar contract wasn’t enough to buy happiness...or safe working conditions.

This completes a story from the life of Hall-of-Famer Dave Parker. Here’s a link to the beginning:

After taking himself out of a game on July 20, 1980, Dave Parker received a visitor in the Pirates’ clubhouse.

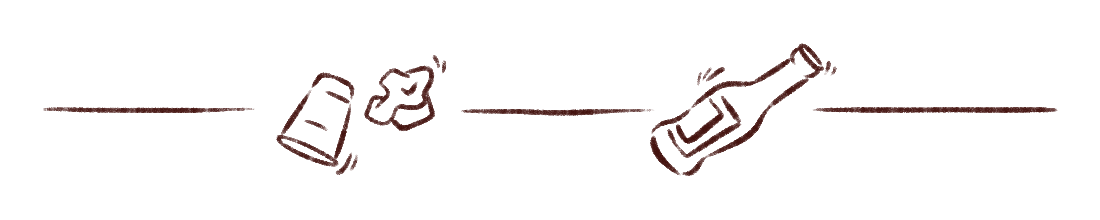

Technically, Dodgers right fielder Reggie Smith was fraternizing with the enemy, but Parker and Smith had a lot in common—their position, their status as Black stars, and the target that seemed fixed on their backs.

While playing in Boston in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Smith had dodged his share of batteries and once wore a batting helmet on defense to protect himself from thrown coins that had been heated up with cigarette lighters. But the older player didn’t need to consult his old scrapbooks to appreciate what Parker was dealing with, only his short-term memory.

While Smith patrolled right field for the Dodgers in Chicago the previous week, someone threw a golf ball at him. He let that slide, but during the next day’s game, somebody threw a hard object wrapped in aluminum foil. Smith told the Dodgers’ manager, Tommy Lasorda, that he was running out of lives to expend on the patrons of Wrigley Field. Any more projectiles and he would see himself out. Just a few innings later, a bleacherite jammed a large chunk of ice jammed inside two paper cups and used this improbably accurate projectile to hit Smith on the hip. The Dodgers played the rest of that day without him.

Smith knew that walking away was the hardest part. After the Duracell incident he came to pat Dave Parker on the shoulder and affirm his decision to exit the game. “That’s the only way that they are going to leave you alone. You did the only thing you could do.”

“Let me tell you, life is more important than a ball game,” Smith told a nearby writer. “I guess you have to be good to be hated. Fans don’t throw things at mediocre or poor ballplayers. But I’m not going out there to be a target.”

Parker agreed: “This is baseball, not war. Sometimes you need to pull your hat low against the lights. I’m not going out there like that. Especially at home.”

Two days later, the Pirates’ slugger announced his desire to be traded out of Pittsburgh and away from the vitriol he felt from some of the fans at Three Rivers Stadium, a move that quickly drew national attention to his plight.

How much danger was Dave Parker facing out there? One columnist jokingly observed that a three-ounce battery was a marked improvement over the improvised sock o’ bolts thrown in the home opener; perhaps people were coming around. But this distinction proved somewhat academic—a physics professor at nearby Carnegie Mellon University estimated that a nine-volt battery thrown from the upper deck could hit with as much force “as a Nolan Ryan fastball.”

The battery thrower was never identified, let alone caught. “We had a couple of security guards in right field,” Harding Peterson, the Pirates’ general manager said, “but it’s very hard to catch one fool. To catch him, the guards have to see him. Somebody needs to point him out.”

In the wake of the Duracell incident, some of the more well-liked Pirates leaped to Parker’s defense.

“He can’t worry about being hit in the head and still play baseball,” manager Chuck Tanner said. “The fans can’t do that…they just can’t do something like that. He plays hard. He’s the best player in baseball. A guy could wind up a vegetable. Why would someone do something like that?”

“Dave is a loud player and he is very emotional,” third baseman Bill Madlock said after the battery incident. “There is also a little bit of a baby in him, despite how tough he is. He wants to be respected. He wants to be loved.”

It is probably not a coincidence that Parker announced he was giving up on Pittsburgh fresh off the events of Willie Stargell Day. At age 29, Dave Parker had almost everything the modern player could want. A closet of gilded hardware, an overstuffed highlight reel, and long-term financial security. The only thing he didn’t have was the proverbial key to the city. Stargell had that, and it seemed as though there was just the one available.

Stargell was doing his best to encourage people to make another copy of that key. “Dave Parker is climbing,” he said.” He’s an extraordinary individual and an exceptional athlete. He, too, is in a position to pass on information and help younger fellows coming along.”

The Pirates’ captain wished people would stop trying to fit Parker for his shoes and let him wear his own. “Everybody is different. No one is asked to compare roses. You have red roses, yellow roses, white roses. For me to compare Parker and [Roberto] Clemente, or Parker and me, is like comparing roses.”

Tanner insisted that Parker wasn’t at war with Pittsburgh. He was at war with a few idiots. “For every one that tries to do something to him, there’s 100 that love him.”

Fools and idiots seemed to be on the march in 1980. Earlier that season, the Tigers’ general manager, Jim Campbell, had waged his own personal crusade against rowdies in the cheap seats at Tiger Stadium, going so far as to close the bleachers entirely to prove who was in charge1. When the seats reopened, the beer cups were distressingly smaller and the crowds stopped tossing beach balls and spare change at visiting outfielders. Campbell claimed a measure of victory. However, he said, “the funny smoke out there is impossible to control.”

Elsewhere that summer, Red Sox right fielder Dwight Evans had called time and gone to get his batting helmet to wear on defense, wanting some extra protection from the rubber-armed fans in the bleachers at Yankee Stadium.

And while there were exceptions, like Evans, and Cincinnati’s Pete Rose (a perennially appealing target for fans on both coasts), baseball commentators noted that Black players were drawing disproportionate fire. Chuck Tanner was asked which players he’d seen come under bombardment and the manager rattled them off on his fingers. Al Oliver in Pittsburgh and in Philadelphia. Dick Allen in Philadelphia and Chicago. Reggie Smith. Parker. There also seemed to be a correlation between how much a player made and how earnestly he was targeted. The Yankees’ Reggie Jackson made no bones about the apparent formula:

It’s racial and financial, and being Black you catch more hard times. Why are they mad at Parker? Because he made a good deal for himself? If he’s not hitting .350 and driving in a million runs, the people aren’t satisfied. He has to rise above that, learn to tolerate it but not accept it, and not let people run him out of town.

The New York Times’ Red Smith, one of the most prominent sports columnists of the era, took notice of what was happening to Parker and other baseball greats. He wondered at the way team sports still tolerated people who abused the talent:

The baseball fan is a curious creature, capable of strangely ambivalent behavior. Put him in a Broadway theater and he will applaud the star’s entrance. Turn him loose in a ballpark and he tries to crown his hero with a bottle. … This ritual is by no means confined to Pittsburgh. It is universally observed and it seems to be on the increase.

The Times’ reporter on the unruly fans beat in this period was Jane Gross, (we at Project 3.18 read Jane Gross the way some people listen to Beyoncé), and after the Duracell incident she asked a sports psychologist, Ronald Kamm, what was stirring up baseball fans. Kamm said the sport had grown more mercenary, and the fans had followed suit. “Sports in the last 20 years has said to people, ‘We only love you for your money.’”

Kamm observed that spectators at sporting events were economically stratified by the price of seats and that “bottles don’t come from the boxes.” He said that most of the disruptive behavior was instigated by “disenfranchised people feeling the most impotent in terms of inflation,” people who enjoyed the way television made them a part of the entertainment. “[These] are lonely, isolated people, trying to make a dent2.”

The psychologist said the advent of television had also put distance between fans and athletes, increasingly separated by the screen:

As [athletes] become more impersonal, you can treat them more impersonally. It’s almost like they want to see if they’re robots or real—if they’ll bleed.

In the afterglow of the 1979 World Series, Dave Parker told a journalist that he planned to focus on public relations in 1980. The modern superstar athlete was also a brand, and a championship was a brand opportunity. With Stargell surely nearing the end of his career, Parker was trying to solidify his own place on the Pirates’ bridge. That all made sense, but Parker had an odd take on the new markets he hoped to open: “I think I’m known by all the fathers and sons. I don’t think I’ve captured the mothers and daughters yet.”

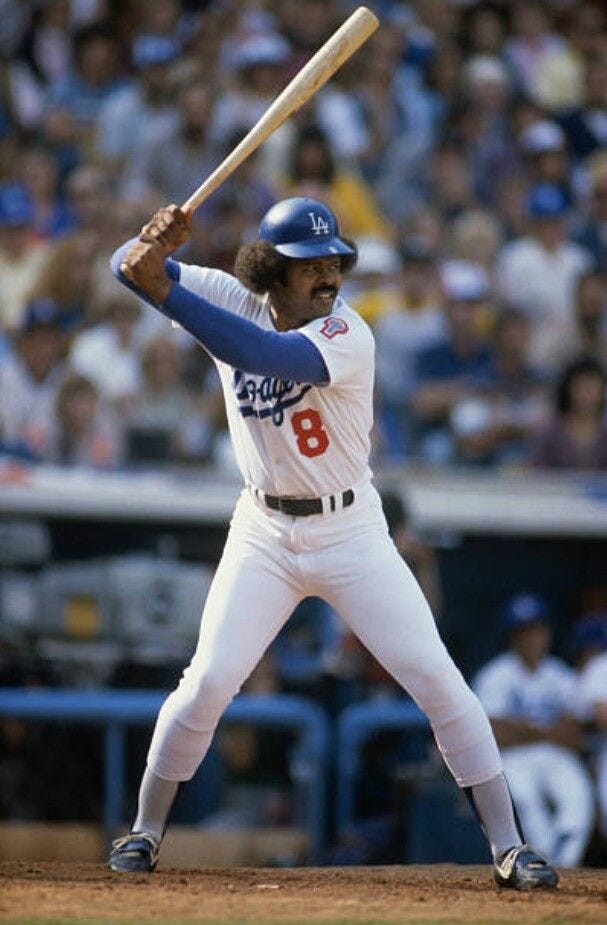

If winning female fans was the goal, something between Parker and his “New York PR agency” clearly got lost in translation. Parker’s summer of publicity materialized as a series of “racy articles” in men’s magazines—periodicals “for the hardcore enthusiasts of the female form,” as one sports reporter delicately described them.

An article in Oui (a publication ostensibly “for the man of the world”), caused Parker the most trouble. He met the writer at a bar—never a good site for an interview—and reportedly engaged in “man’s talk” without realizing said talk was on the record, despite the presence of the journalist’s tape recorder on the table, catching every manly word.

In their conversation, Parker repeated that a player with his salary was misunderstood in Pittsburgh and continued to reduce the city of 420,000 people down to a one-size characterization you’d expect from a bad political ad:

Pittsburgh is a blue-collar city where guys work from 9 to 5, working at the steel mills, at the coal mines, getting black lung. These cats can’t relate to the law of supply and demand.

He said baseball itself was an odd fit for Pittsburgh, which he said was a football town, a “place that can relate to guys going out and crushing each other.”

He joked about the time-honored tradition of baseball players making more money than the President of the United States. Jimmy Carter made a tenth of his salary, but Parker was sure he was doing “10 times the job [the President’s] doing.”

While the article’s clearly sensationalist tilt made it less newsworthy (he would later assert that his comments were “distorted”), Parker’s continuing hard feelings needed no embellishing. Asked about his apparent absence from the Pirates’ World Series victory parade, he showed how much the boos he’d received in 1979 had stuck with him: “Why should I (attend)? Where were [the fans] when I needed them?”

Though his PR firm was surely doing him no favors by throwing him to the men’s mags, Parker did himself several disservices as well. He reportedly declined a number of Pirates-sanctioned public appearances, creating a void that outlets filled with reports on his personal challenges. His separation from his common-law wife regularly made the news, and baseball’s highest-paid player faced multiple lawsuits alleging non-payment, including one brought by a decidedly blue-collar landscaper. Imagine the headline: “Millionaire ducks yard work bill.” Parker might as well have cut in front of a retired coal miner waiting in line at the grocery store.

Parker was pensive in the Pirates’ clubhouse, often sitting alone and wearing headphones. In better times he had said, “in the clubhouse, I’m a different animal. I eat bats. I tear stools. I turn over lockers. This is the way I get up for the game.” His teammates waited for him to resume prowling among the lockers and hurling insults, which they’d take as a sign he was feeling better.

Second baseman Phil Garner, the clubhouse Statler to Parker’s Waldorf, did his best to push the right buttons, arriving one day to model another cutting edge helmet for Parker to use—this one specially adapted for playing the outfield at Three Rivers Stadium.

Meanwhile, Parker’s agent, Tom Reich, who’d spent so much time fashioning his long-term pact with Pittsburgh, was now trying to talk him out of tearing it up by forcing a trade.

“If he is physically able to play, I have a strong feeling Dave will respond to all of his grief with a superhuman effort on the field. He is that kind of man.” Reich’s cause was helped by the fact that not many teams were looking to take on the richest contract in baseball, less two years and one leg.

Parker put out a few public feelers of his own. “I think I’d be better off playing elsewhere, maybe Philadelphia3.”

To his credit, Parker’s comments about his difficulties evolved—slowly. He told a Chicago columnist “I guess it all goes back to the money,” but managed to avoid singling out any particular fanbase.

We’re artists, we’re onstage. I understand that. But I don’t understand why, if a comedian on the Johnny Carson show bombs out, the audience only hisses. But when we make outs 7 out of 10 times, which we’re going to do no matter how much money we make, people try to ruin us.

“There's resentment,” he said. “The same politics of life extend to the baseball field. People resent a Black man making more and more money, especially when the economy is the way it is.”

None of these politics were confined to any one place in America. “Any guy who’s boisterous and Black, it’s going to be tough,” said Bill Robinson, the Pirates’ 37-year-old back-up first baseman. “Name me any city where it isn’t.”

By August 23, Parker had accepted that Pete Rose and Mike Schmidt weren’t coming for him in an evac chopper.

“I don’t really want to be traded,” he said, bringing the saga to an end. “I just wanted to shake up the people in Pittsburgh. I wanted to say ‘Hey, I feel serious enough about this to leave.’ I don’t think the whole city should suffer. It was just one or two people creating these problems.”

It helped that things in right field at Three Rivers had settled down. Parker hoped that was a reflection of the many good fans throwing their weight around out there. “I think true fans know what a serious problem it was.”

In many ways the trade demand was Parker’s best PR effort that year. The ensuing national attention gave people a look at the person behind the talent and the contract: wealthy, yes; successful, certainly; but also thoughtful, vulnerable, and probably a little thin-skinned. But the focus on the physical pain he was battling and the mental hurt he felt showed Dave Parker was giving all he could. And when his best wasn’t the best, no one took it harder.

Parker still played far more than he sat that summer, managing to stay on his feet by having fluid drained out of his knee on a regular basis. But he was so day-to-day that Chuck Tanner’s regular routine was to come to the ballpark and find Parker to ask him if he could start. He hit an embarrassing .247 in July, most of that before the Duracell incident. And then the wounded player hit .354 in August, determined to show who he was, bad knee and all.

Going into play on September 4, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh held a share of first place in the hard-fought National League East. Tanner checked with Parker. “I almost scratched myself from the lineup,” Parker said. “I’d had some more problems with the knee.”

He ultimately decided to start that night’s game against the Houston Astros and ended up leaving early again, but this time under far different circumstances.

He singled in the first inning. He hit a two-run home run in the third. Another two-run home run in the fifth earned him a standing ovation and put the game away. He hit another single in the seventh and limped to first base. Tanner, a master mediator, saw his chance. He sent in a pinch runner and let Parker walk off the field with a sublimely perfect night.

Dave Parker’s batting average rose from .299 to .305 that night, the first time he’d been over .300 since early May. It was a performance worthy of folklore, and however they felt about Rockefellers, most Americans couldn’t resist a person suffering on their way to doing great deeds. As he walked off the field, the fans in Three Rivers Stadium gave Parker his second standing ovation in less than an hour.

Despite his thoroughly mixed emotions, Parker tipped his cap to acknowledge the cheering crowd. Asked about that gesture, he said, “I’m just happy that I had a good day and the fans acknowledged it.”

It must have been enormously difficult to work through those feelings on such a public stage, but he was giving the task his all. Dave Parker had once promised to give 110% out on the field no matter what, but a 4-for-4 night at the plate was only 100%. The cap-tip was the rest.

ICYMI: Campbell vs. the Bleachers.

”...make a dent.” Very solid projectile pun there from Dr. Kamm.

The Phillies were a serious contender in 1980, but so were the Pirates. Playoff hopes being equal, seeking a rebound relationship with the toughest sports fans in the country suggests Parker hadn’t really thought this plan through.

Stellar work. Glad I'm here.

I've had the book "Cobra" sitting on my desk for a long time. I'll eventually get to it, but your writing has really opened my eyes.

I knew Reggie Smith faced some incredible challenges, but I honestly didn't realize how bad it was for Parker.

I was 8 years old and my earliest memory of baseball on TV was the 79 World Series. I watched it in black and white (which seems somewhat poetic here) on a tiny portable TV with my old man.

It's truly tragic that Dave won't be able to be on that stage in Cooperstown. And we are worse off for not getting to hear what the man might have said. Thanks, Paul.