Postscripts - Vol. 4

A St. Patty’s massacre, another team is burgled, and the joy of bobbleheads.

We spent most of last week at the Society of American Baseball Researchers 2025 conference in Dallas, Texas. We gave a Billy Earle talk on Saturday (Topic: “How haunted was he, really?”) and put another satisfying dent in our mission to make sure everybody knows about this guy.

Pro-tip though: if you have 20 minutes to present, DON’T present on a person’s whole life; and if you DO present on a person’s whole life, DON’T present on someone whose professional playing career looks like this:

But Project 3.18 is never far from our thoughts, and we made time during our trip to add on to a few existing stories, receiving assists from our friend Gordon (The Athlete Archives), and Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the MLB Players’ Association. Really.

If you’re new around here, greetings and welcome! Click one of the links on this page to read a baseball story we know you’ll love.

Postscript: Green with Enmity

Required Reading: The Baseball Strike of 1972

Today’s photo-forward edition starts with a most unlikely candid.

It’s black and white, so we’ll give you two important clues in terms of what’s happening here. The hats everyone’s wearing are green, and the date is March 17, 1972.

At first all you can see is a bit of awkward silliness, but once you know the story behind this photo, it takes some darker hues.

O’Malley was throwing his annual St. Patrick’s Day party. With the players and owners locked in a dispute over pension funding and just a few weeks before the season began, the Millers and Moss received an invitation. Miller was not really the kind of guy who enjoyed parties where you have to wear cardboard hats, but given O’Malley’s clout with the owners Miller thought, what the heck? Maybe they could find a way to ease the deadlock.

We’ll let Miller tell you what happened, from his autobiography, A Whole Different Ball Game:

The party was a big league bash. Everything was green: water, scotch, beer, potatoes, tablecloths, you name it. O'Malley had chartered a plane from Los Angeles with scores of season-ticket holders and everybody was whooping it up. I hadn't been there very long before I began to feel uncomfortable—none of the current players had been invited.

Dick and I were summoned to meet with Walter and his son Peter O'Malley. O'Malley Sr., his party hat still perched on his huge head, was puffing on a fat cigar, laying a cloud of smoke through the room.

We got down to business quickly:

"Walter, I don't really understand what's going on. This isn't a new issue. And we're not asking for anything out of the ordinary. The amount of money separating us isn't even that large, certainly not large enough to require a strike.”

O'Malley said, "Oh, well, don't worry. There's not going to be a strike. We'll resolve this."

I told him I hoped he was right, but that it was getting close to the deadline.

"A lot can happen in two weeks," he said, sipping a glass of green scotch.

As I stood up to leave, O'Malley said, "I heard the [Dodgers vote to strike] was 21 [in favor of striking] to four [against]. Who were the four?"

I thought he was kidding. He wasn't.

"I have no idea," I said, "but I wouldn't tell you if I did. Why do you want to know?"

"A baseball team is only as good as its unity," O’Malley said. "I don't want players that cast themselves as management tools on my team. Don't get me wrong, I'd prefer the players to vote unanimously not to strike, but if the majority decides to walk out, I don't want dissenters on my club opposing their teammates. A winning ball club is unified, not split."

Later, I learned the players' identities, and I realized O'Malley had been telling the truth. That season, two were traded, and the other two retired.

I left the meeting with O'Malley convinced for the first time that there would be a showdown by March 31.

Miller learned an important lesson that day. Never relax around a man so ruthless he’d steal the Dodgers out of Brooklyn; make commissioners his puppets; and use his St. Patrick’s Day party to try and weed out dissidents on his team—even though said dissidents supported his position.

And, above all, don’t drink the green scotch until you see Walter drink it first.

Postscript: What’s That Ball Game?

Recommended Reading: The Zoo is Closed

Preparing our story on bad behavior in the Tiger Stadium bleachers, we were delighted to encounter this photograph, taken by Thomas Hagerty at some point in the late 1970s (we see bell-bottoms). Looking at the stadium’s massive scoreboard as Hagerty captured it, we wondered if there was enough visual information presented to determine exactly when the photo was taken.

Narrowing it down was easy enough. In addition to Detroit vs Cleveland, at the far right of the shot we can clearly see two other sets of teams listed as playing each other that day:

New York Mets vs Montreal Expos Pittsburgh Pirates vs Philadelphia Phillies

We used Baseball Reference to identify the handful of dates between 1975 and 1980 when all three sets of teams were playing as shown. But how could we narrow it down further.

We noticed that the scoreboard listed the umpires officiating that day, by number, so we tried using those numbers to figure out what American League umpires were working each of our suspect games and see if we could find a match.

We eventually discovered that American League umpires were not even assigned numbers until 1980, so what were these numbers?

Retired American League umpire Dave Phillips later cleared this up for us via an offhand passage in his autobiography, Center Field Is On Fire:

Before we actually wore numbers on our shirts or jackets, in a lot of cities, the teams gave umpires numbers, usually in alphabetical order, so they could put the numbers on the scoreboard and the fans would know who was working which base.

In other words, the umpire numbers shown in that photo were essentially a code, and we did not have the cipher. Back to the drawing board.

Looking for any other usable information, we stared at the partially obstructed characters presented just below the umpire numbers:

CLEV 2…OR 14 15 16

Could that be something? 14…15…16…three consecutive numbers, like a series played on three consecutive days? “CLEV” was obviously an abbreviation for Cleveland, so perhaps the obstructed letters below that were “TOR,” for Toronto. This eliminated several potential dates because the Blue Jays didn’t exist prior to 1977.

Did Detroit ever play the Toronto Blue Jays in a three game series over the 14th, 15th, and 16th days of a month in the late 1970s? Yes, in June 1977. That month, the Tigers also played Cleveland—on June 2.

And that made June 1, 1977 the date when Thomas Hagerty took this photograph in the bleachers at Tiger Stadium, before the night game began.

We did it!1

Here’s our mystery game:

On June 1, 1977, the Tigers lost to the Indians, 6-4, in front of 17,718 fans.

Trying to regain the phenom-form he’d had a year earlier, Mark Fidrych pitched a disappointing game for Detroit, giving up 10 hits and five runs. His surgically repaired knee was functional, but this Bird was nothing like the phoenix that torched the American league and won 19 victories as a rookie in 1976.

“There’s some little thing missing,” Fidrych said. “All I have to do is find that one little thing and I’ll be okay.”

Sadly for the Bird, this would prove much easier said than done.

Postscript: Bobbleheading Disaster

Required Reading: Fire Watch

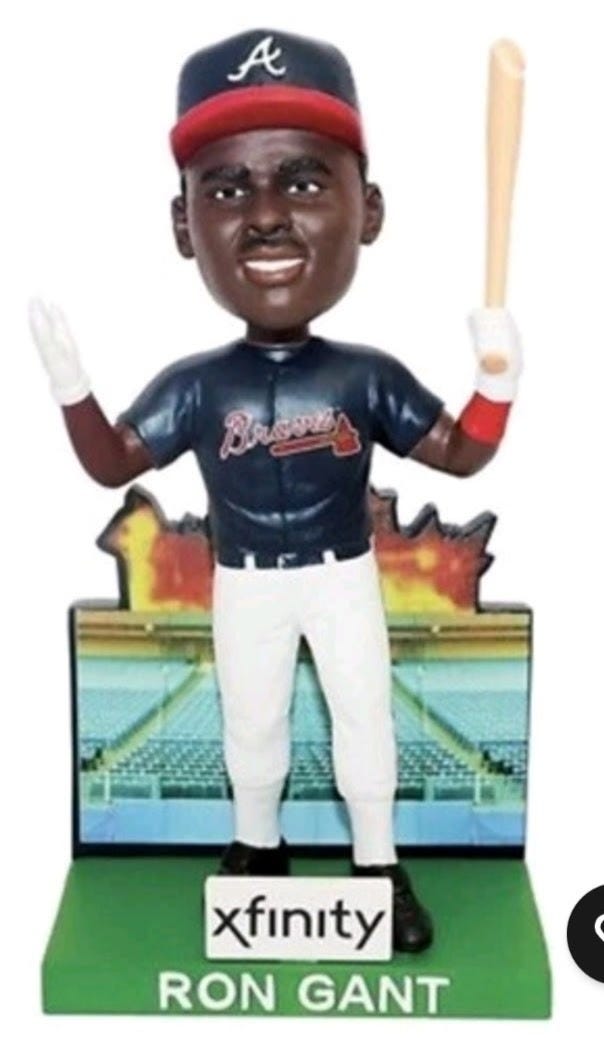

In our piece on the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium fire of 1993, we featured a famous photograph of Braves left fielder Ron Gant posing in front of the out-of-control fire burning in the ballpark:

How do we know this photograph is famous, you ask? Thanks to our friend Gordon, a Georgian by life if not by birth, who was soon in our inbox to make sure we knew about this:

Bobbleheads are one of the great American art forms. If someone here wants to start a Substack about bobbleheads, you have our subscription (and probably many others).

Programming note: We’re getting together with Gordon this week to talk Ty Cobb, Claude Lucker, and Al Travers for an episode of his YouTube show, The Athlete Archives. It’s going to be fun, and we’ll share a link when the episode is released.

In the meantime, we beseech you to check out one of Gordon’s latest. It looks unassuming, and we’d never heard of this guy, but in just six minutes, Gordon tells one of the best baseball stories we’ve ever heard.

So credit to Gordon for reviving the true story of Mills who, in 1916, was not just a one-man team, he was a one-man major league:

Count on Rupe Mills getting his name in a Project 3.18 feature some day soon.

Postscript: On the Thieves’ Trail

Required Reading: The Seattle Mariners Go Thrifting

Earlier this year we reheated a cold-case: a break-in on May 30, 1981 at Arlington Stadium in Texas. The perpetrators relieved the visiting Seattle Mariners of most of their equipment before a game against the Rangers. The Mariners were reduced to raiding the park’s souvenir stands for caps and jerseys, but no Mariners’ merch was to be had, so the team pivoted to a color-aligned alternative, the livery of the Milwaukee Brewers.

We’ve continued our investigation, and it turns out these thieves had struck before:

During the night of June 12, 1977, someone inside County Stadium in Milwaukee managed to gain entry to the locked visitors’ clubhouse. That clubhouse was inhabited by the Kansas City Royals at the time, and it was stuffed full of jerseys, bats, spikes, jackets, and gloves.

The intruders moved with quiet precision, taking gloves, shoes, and especially jersey tops. The Royals traveled with 60 jerseys, two per person. Six had been taken home by the visitors’ clubhouse manager for washing (George Brett’s was among these, naturally2 All but one of the 54 uniforms in the clubhouse were taken, and the theft was not discovered until the next morning.

“I put my key into the lock and it wouldn’t turn,” the clubhouse manager said. “Then I pushed the door and it was open, and I saw right away that there were no jerseys. It was a very neat job. Every chair was in front of every locker, the same as we left them yesterday.”

Twenty gloves, one catcher’s mitt, 20 batting gloves, 10 pairs of spikes, and 15 windbreakers were taken, a haul worth $3,500 on the burgeoning black market for “hot” baseball merchandise.

The manager and coaches’ uniforms were taken, too. “This is the first time this ever happened to me,” Whitey Herzog said. “But I was on some really bad teams and nobody wanted our shirts.”

For the Royals, the most impactful losses were the gloves they’d carefully broken in and maintained for years.

“Why that glove?” shortstop Fred Patek said. “I’ve used that glove in every big league game I’ve ever played—10 years with the same glove. I’ve got this glove I’ve been breaking in for a couple of years but I’ve never used it after spring training. I can’t understand why they didn’t take the newer glove.”

Center fielder Amos Otis had had an eight-year-old glove taken in Boston a few years back. Now its replacement was gone, too. “This one was four years old. I’ll just have to get another old glove from somebody. I give my new gloves away.”

Second baseman Frank White’s infielder’s glove had been left in his locker, and he had a theory. “They didn’t want mine,” he said. “It’s too small for softball.”

The Milwaukee police responded to the scene before the Sunday game. They already had a person of interest—Royals’ pitcher Jim Colborn.

Colborn had been traded to Kansas City from Milwaukee in the offseason, meaning he was quite familiar with the County Stadium facilities and rhythms of activity. He was also the only player whose uniform had been left—it had not been hanging up and had been missed. Colborn was also a notorious practical joker. “This isn’t one of your jokes, is it?” the officer asked him.

If press accounts are to be believed, Colborn also spoke almost entirely in one-liners that would have made him a tough police interview (and a sports reporter’s dream). The pitcher must have had a (prearranged?) alibi, because instead of being arrested he started the day’s game for Kansas City and lost.

Just as they would four years later, the victimized team ended up in Milwaukee apparel. The Royals engaged in some light jousting over whose uniform they would borrow. Amos Otis tried to get Hank Aaron’s #44 out of a display case outside the clubhouse, but this request was gently rebuffed.

That night’s game must have been a scorekeeper’s worst nightmare. In it, the real Brewers defeated the impostors. “It felt like we were beating ourselves out there,” Brewers manager Alex Grammas said, giving delightful new life to a cliched turn of phrase.

The Royals were the Royals again by their next series—unlike Seattle, Kansas City had enough surplus on hand to express replacements to New York ahead of the team’s arrival.

The case has never been solved, but rest assured we’re building a file and keeping an ear on police frequencies. The next time the thieves strike, they may make a crucial mistake (they’re much older, after all).

With that, we’re off to try and figure out if Jim Colborn was anywhere near Arlington Stadium in Texas on May 30, 1981. We might blow this thing wide open.

Know anyone who enjoys baseball stories? Support our work and send Project 3.18 their way.

Hall-of-Famer Dave Parker passed away last week, just weeks before his July induction ceremony in Cooperstown. Dick Allen wasn’t given a chance to know he’d been elected, let alone to see it happen, and we were glad the Hall had caught up to Dave Parker during his lifetime. But no, too slow again.

Next week Project 3.18 will feature the Cobra in all his brilliance, brashness, and complexity.

Old scoreboards all spoke the language of baseball, but each one had a slightly different dialect. We ourselves are fluent in Wrigley, but someone better-acquainted with the scoreboard at Tiger Stadium would surely have made much quicker work of this challenge.

We were irritated to learn that George Brett’s uniform wasn’t stolen. If it had been, June 12, 1977 would have been the only night of his entire major-league career that Brett wore the uniform of any other team, and for the most absurd reason. But alas, his record is perfect. Forever Royal.

I'm impressed by the research effort to identify the scoreboard photo date. It's the kind of rabbit hole I sometimes find myself in but more often than not it ends without an answer. Celebrate the victory!

The Marvin Miller story is great. I have to read his autobiography. Some day I'll make the transition to Audible, but for now I still prefer holding a book and turning the pages. It's not as time efficient but there's something therapeutic about it.

And Paul, thank you for the shout out regarding Mr. Rupert Mills. Truly a unique man, one to add to your "fun to hang" list. I look forward to whatever you end up writing about the man. Your research is surely going to uncover more than what I found.

Great read Paul! Sorry I did not make it to meet you at SABR 53 this year but hope to rectify that in 2026!