Seeing Saffron

We’re hunting history with help from two awesome readers.

We love it when Project 3.18 gives us a chance to tell some freewheeling stories with fans of the game and its history. You’ll never know what sharing a memory in a comment or sending an interesting photo our way will inspire here, but whatever it is will probably be fun.

Back at the beginning of August, we got an email from Roger Jackson, Project 3.18’s part-time researcher and full-time uncle. Roger was traveling through upstate New York and his itinerary included a visit to Cooperstown and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Writing back, we suggested Roger check out the Frederick H. Rahr-designed yellow baseball that is a part of the Museum’s enormous collection and the subject of a recent story here. I’ll make the story link large so as to give a good look at one of these treasures (the Museum has three of them):

With an offhand recommendation, we’d inadvertently given our intrepid researcher his next assignment, and when he visited the museum, he got right to work.

The results were, well, a little enormously disappointing. Here is Roger’s after-action report:

The first two people I asked about the yellow baseball had no idea what I was talking about.

The third directed me to the Savannah Bananas exhibit.

Ooof.

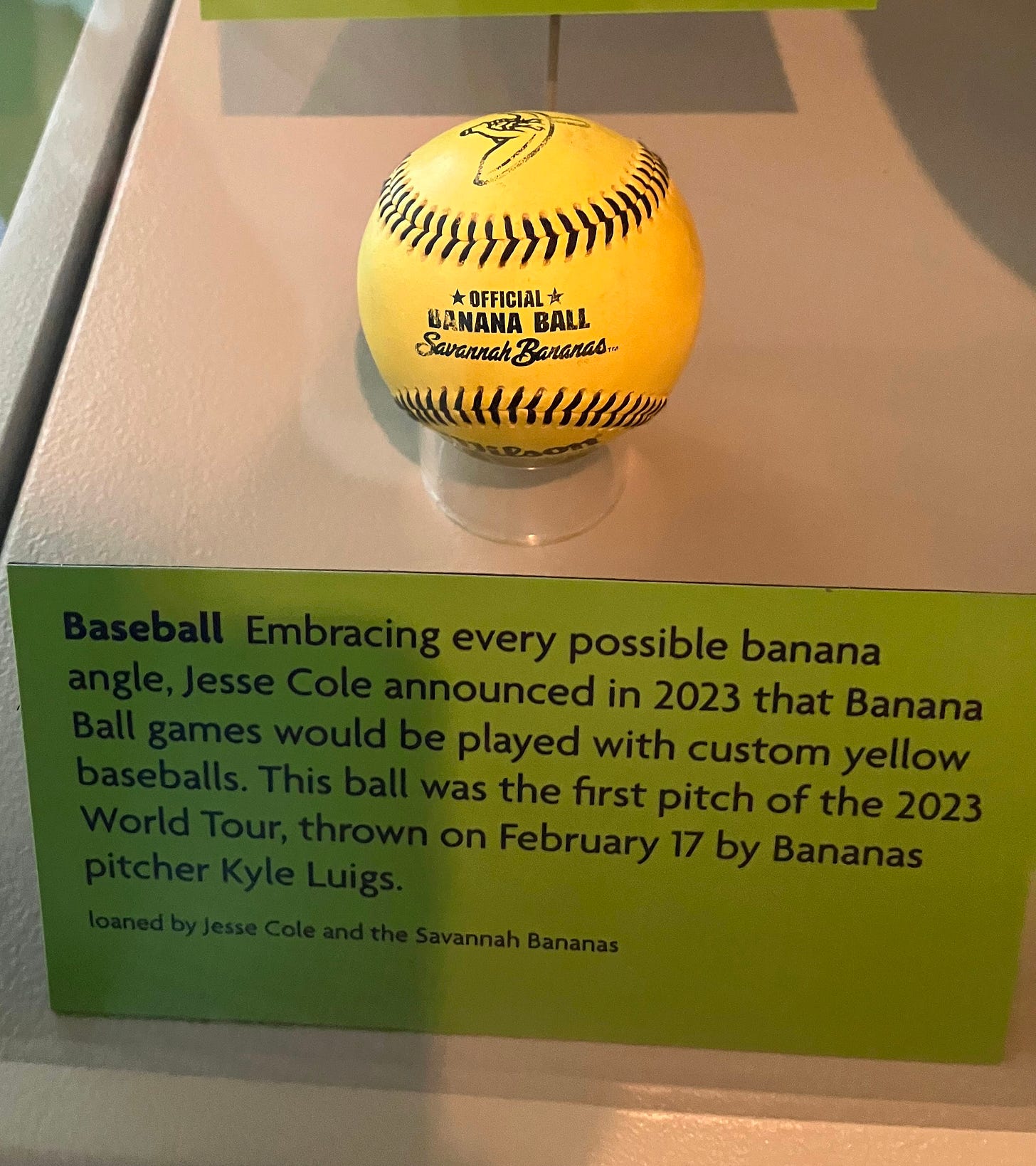

This, according to an official representative of the Hall of Fame, is the yellow ball:

Look, we get it—the Museum can only keep a small part of its collection on display, and apparently the only non-white ball used in modern AL/NL history isn’t cutting the proverbial mustard. But this seems like a missed opportunity, doesn’t it?

Especially in a moment when the Bananaball is on display, shouldn’t the National League’s original yellow baseballs be featured somewhere nearby? Curatorial studies majors, who’s with us on this?

Project 3.18 readers, we need your help. If you are traveling to Cooperstown and the Hall of Fame, please continue to make polite inquiries about “the 1938 yellow ball,” and accept no substitutes. And if you know anyone connected to the Museum, please send this curatorial lay-up their way. When one yellow ball is featured, let’s get them all out!

The next reported sighting of a yellow ball came from stalwart reader Jeff, who mentioned in a comment that he’d seen a yellow baseball in a recent trip to Yankee Stadium and, recalling our story, took a picture. Jeff made it clear that he didn’t know if this was the yellow ball, from 1938, but it was at least a baseball that was yellowish.

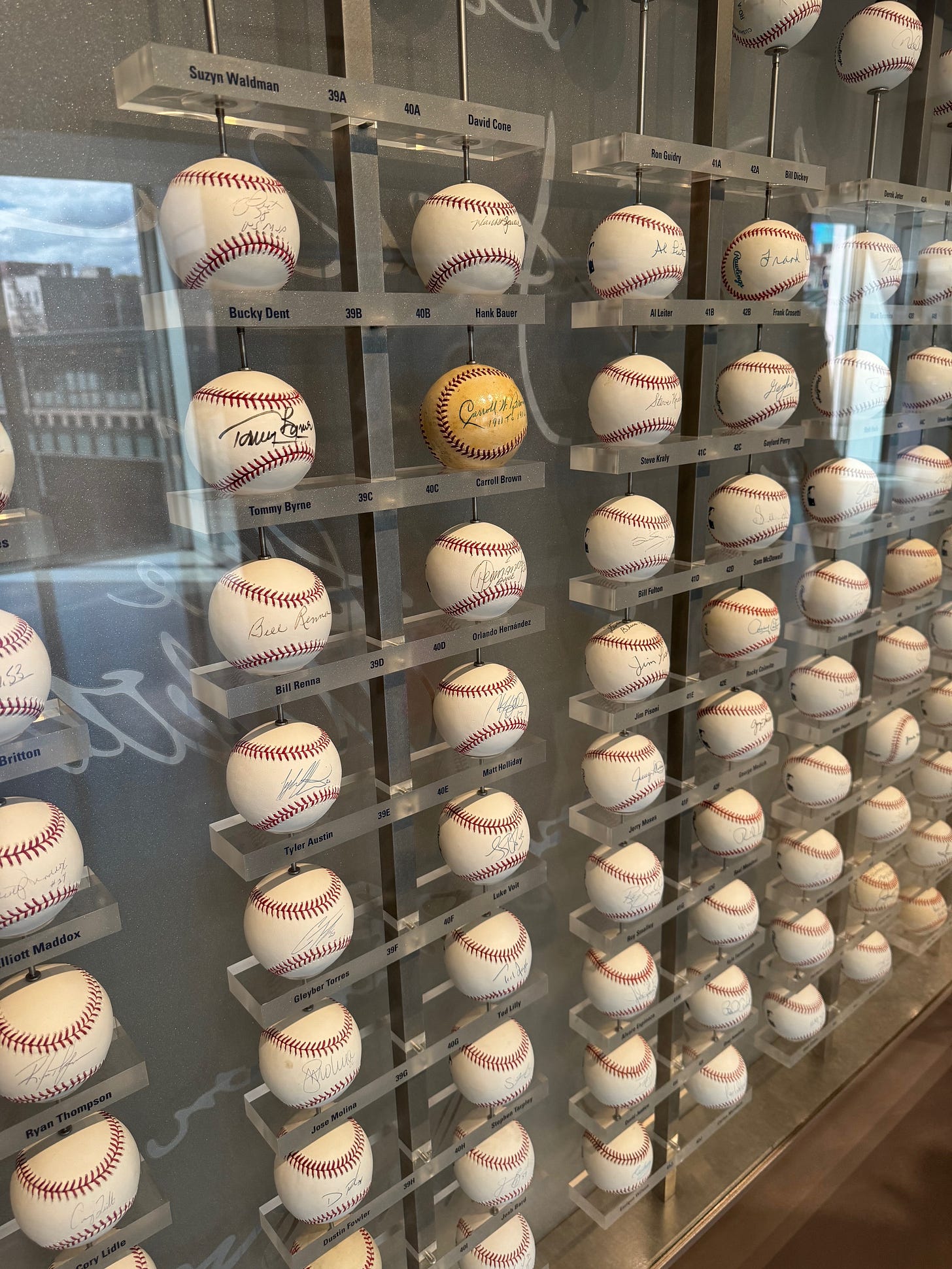

Jeff’s photo, which we’ll get to in a moment, captures a small portion of a large exhibit on display inside the Yankees Museum, which is itself inside Yankee Stadium, which is inside the Bronx, and so on.

The Yankees Museum has taken on an ambitious project. They are trying to collect an individually autographed baseball for every Yankee in history, inclusive of any player that wore the Yankees’ uniform and appeared in a minimum of one regular season game. Nowadays they just make everyone sign a ball after that first game, but trying to find the older autographs is the real trick when you have a franchise that just turned 122.

Here’s a photo of the autograph display from the Museum website. In this segment, every ball is white. Some are a little dirty, sure, but dirty ain’t the same as yellow.

Now let’s take a look at what caught Jeff’s eye in another section of the display:

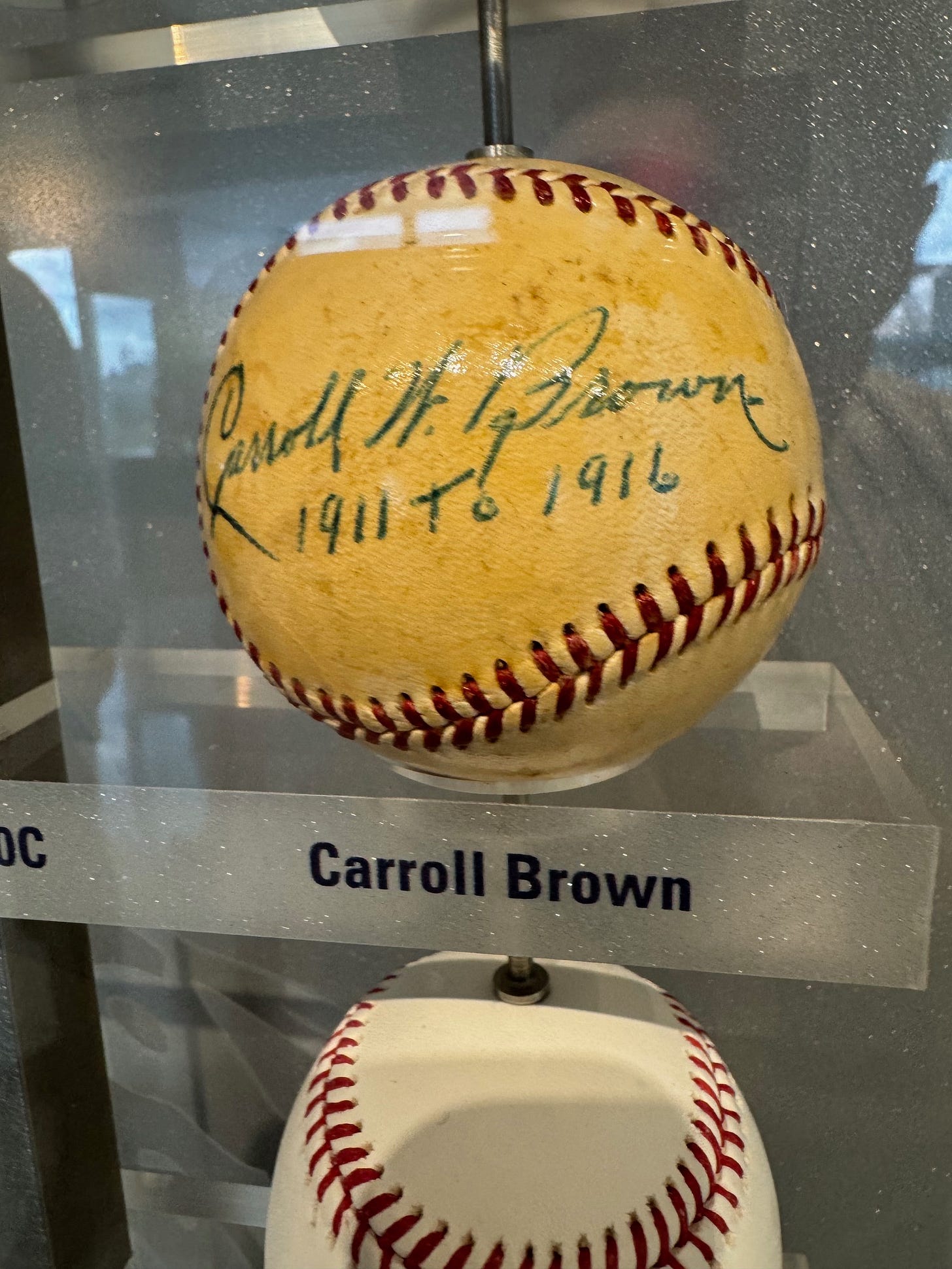

We were hoping to learn that the signer, Carroll Brown, played in the late 1930s, when the Rahr-specific yellow ball was used, but the dates printed on Brown’s ball seemingly ruled that out, and left us with questions.

How did Carroll Brown get a yellow baseball some 20 years before New York’s preeminent color actuary started making them? And, while we’re at it, who the heck is Carroll Brown?

Carroll Brown was a right-handed pitcher with the Philadelphia Athletics and, for parts of two seasons, the New York Yankees. Brown has already given the years he pitched—written under his signature—but he’s a somewhat unreliable narrator in that he’s including one year of minor-league service. Brown’s last major league season, with New York, was 1915.

Project 3.18 got a little carried away digging into Brown’s history, so we’ll limit ourselves to sharing Five Fun Facts about the man they called “Boardwalk.”

1. This man had a Crayola crayon named in his honor.

Carroll Brown was a native of Atlantic City, New Jersey, a resort/tourist beach town famous for the raised wooden boardwalk that was first installed in 1870 to help keep the ubiquitous sand from being tracked inside buildings of the growing entertainment district. The miles-long boardwalk became Atlantic City’s signature attraction, and when Carroll Brown reached the majors with Philadelphia in 1911, his new teammates quickly settled on his alliterative nickname.

In 2004 Crayola held a competition to identify a signature color for all 50 states. Participants could suggest a new (temporary) name for an existing color, and the winner for the state of New Jersey was a woman who suggested “Tumbleweed” become “Boardwalk Brown.” The name was understood to be a reference to boardwalk districts up and down the Jersey shore, but we got the real joke—this was a deep-cut baseball Easter egg that went unappreciated in its time, even by Brown’s hometown Atlantic City Press:

Sure, we’re glad the color honors the state’s great boardwalks. But why not choose something with more color wheel pizazz, like Garden State Green?

2. Oh, Boardwalk Brown had pizazz, let me tell you.

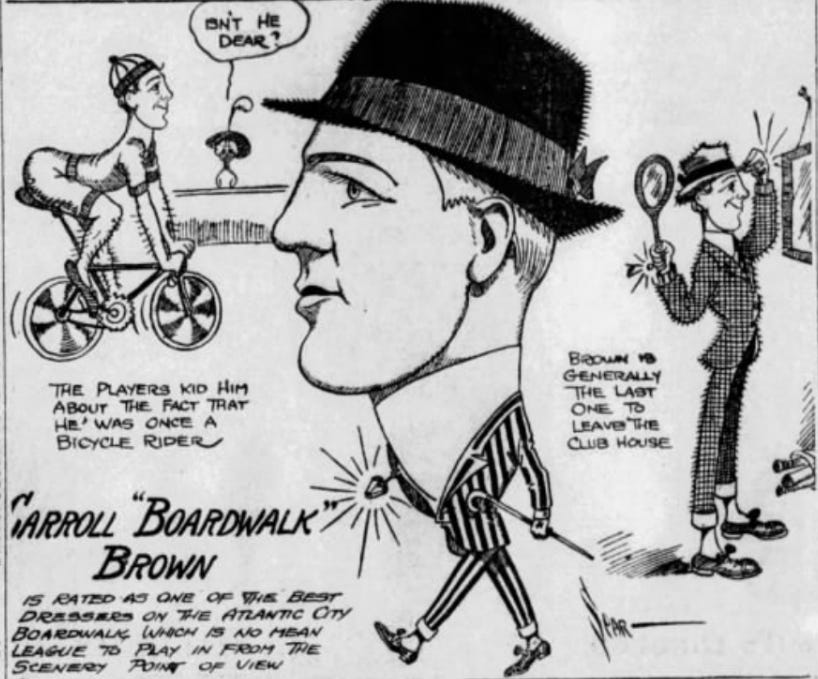

In 1913, he was lauded as one of the sharpest dressers in Philadelphia sports:

Boardwalk is in no sense a rapid dresser. No, he takes his time to be sure that everything will be properly adjusted. He is sartorially meticulous in the extreme.

As depicted in this wonderful accompanying illustration, he was also known for wearing diamonds when strutting about back home in Atlantic City:

3. He once set the American League record for walks issued in a game—and won.

On July 12, 1913, Brown gave up a whopping 15 walks in 7 ⅔ innings of work.

But that’s not the whole story. While Brown unquestionably had struggles with his command, he set that record on “an exceptionally windy day” at Detroit’s Navin Field, and the wind produced a mess of a game featuring 29 hits, 23 walks, and a smattering of passed balls, hit batters, and wild pitches. The Tigers had six errors; Brown was clearly not the only one struggling out there.

Despite issuing 13 walks in the first seven innings, Brown escaped again and again, giving up just a single run while the Athletics built a large lead. Only in the eighth did his luck fail him, with his last two walks contributing to four Tiger runs. When he was finally pulled, witnesses estimated he’d thrown about 200 pitches. The Athletics went on to win, 16-9. Brown was credited with that win, and rightfully so.

4. Brown was the victim in one of our favorite strikeouts from all of baseball history.

A few months ago, we brought you the story of Aloysius “Al” Travers, a Philadelphia seminary student with no pitching experience who, on one inglorious day in 1912, pitched a complete game for the major league Detroit Tigers. It may be our favorite story to date.

Facing a Philadelphia Athletics lineup that regularly gave major league pitchers fits, Travers was thumped. He gave up 24 runs in what remains the single worst complete-game performance in official AL/NL history.

But Travers had pluck, and we wrote admiringly of the fact that he pitched in that game and got any outs at all:

Al Travers went the distance—eight innings, 24 runs, 23 of them earned, seven walks … and one glorious big-league strikeout.

The only player ever to fail to put the ball in play against Al Travers was Boardwalk Brown, the second of three pitchers the Athletics used in that farce of a game.

Brown would probably want us to note that in his three at-bats against Travers, he had two hits, two runs, and two RBI.

Yeah, and one glorious strikeout.

5. It’s actually just Four Fun Facts about Boardwalk Brown. Sorry.

We assumed we could find a fifth one but the drop-off was steep.

While it had its moments, Carroll Brown’s biography unfortunately offered no connections to a proto-yellow baseball. We still didn’t even know how old the signed ball in the Yankees Museum was.

The museum website helpfully mentions that individually signed baseballs were extremely rare in the first half of the 20th century; the oldest ball in the display—signed by Lou Gehrig—dates to 1933. What that tells us for our purposes here is that Carroll Brown’s signed ball does not originate from his playing days; he just wanted to list those years when, sometime after 1933, he signed a ball for somebody.

So, could Brown have signed a regulation yellow ball somewhere around 1938 or 1939—when such balls were in circulation? It was still possible. But to say one way or the other, we needed a look at the back of the ball.

In the 1930s all regulation balls were stamped with the name of the president of the league in which they’d be used. Ford Frick was the National League president then; he was also the guy that gave a yellow ball his (interim) blessing. No American League teams ever tried Rahr’s creation in an official game, so any “true” yellow ball is going to have Ford Frick’s name on it.

So, whose name was printed Carroll Brown’s ball?

If you ever have to email a museum or other cultural institution, the magic words to put in the subject line are “Scholar Inquiry.” Museums love scholars, and the label is extremely subjective.

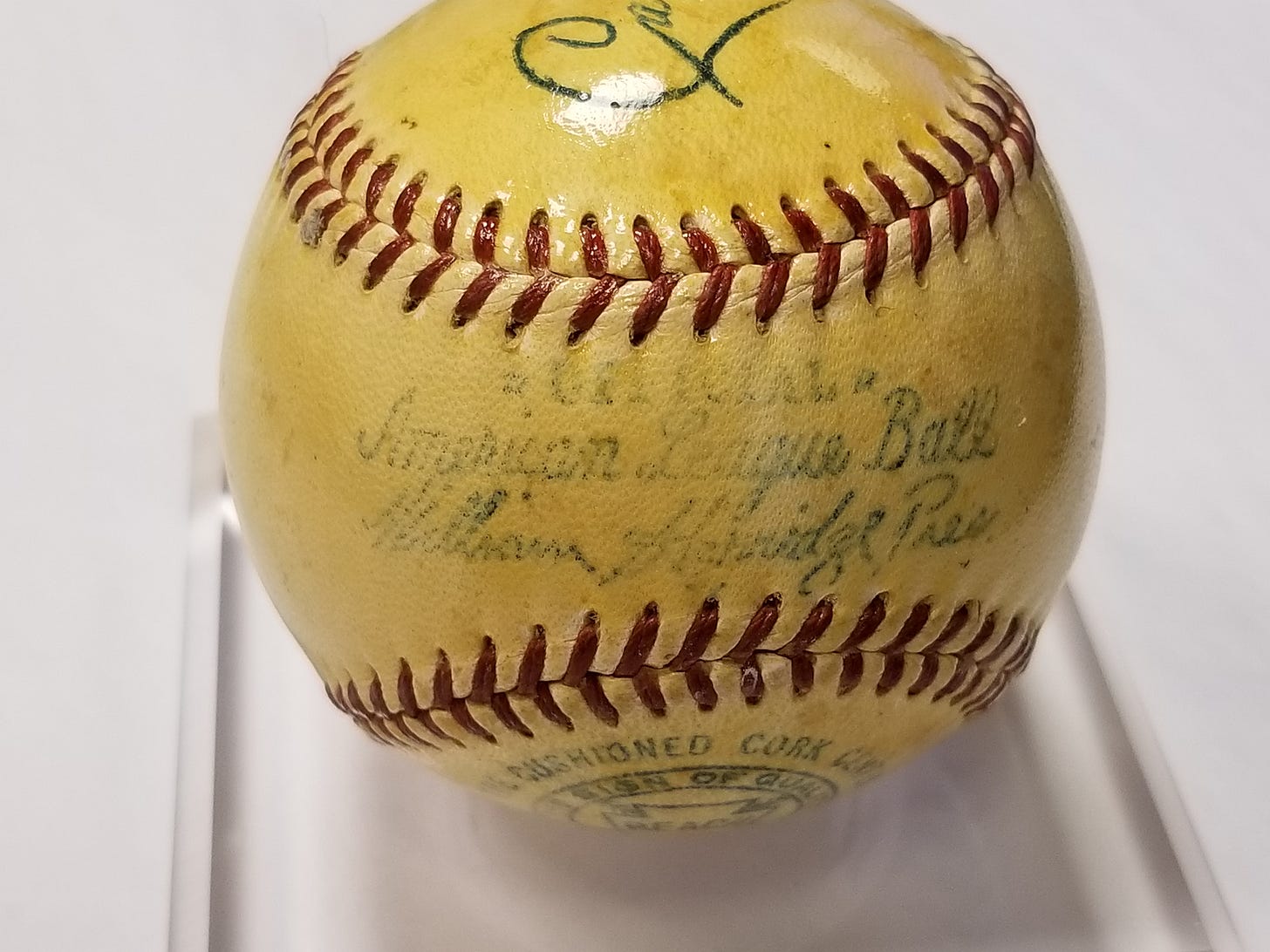

This is how we connected with Brian Richards, the Senior Museum Curator at Yankee Stadium, perhaps the coolest job in the world. Our scholarly request to see the back of Carroll Brown’s ball didn’t phase Brian one bit, and he quickly delivered the goods:

So there we have it. This is an American League ball bearing the printed signature of William Harridge, the AL president from 1931 to 1958. It is only fitting that Brown, a one-time American League recordholder for walks issued in a game, had signed an AL ball.

Okay, so this was not a Rahrball, but why was it so yellow??

If you are a memorabilia collector of any seriousness, you may already know the answer, but Brian had to clue us in:

It is not actually yellow in color. Rather, the ball was coated in shellac following its signing. Shellacking an autographed baseball was a common means of “sealing” its signatures. This practice is discouraged now, as deterioration to the shellac causes peeling/flaking. This ultimately damages the autographs, if not destroying them altogether. Fortunately, the Brown baseball has been well cared-for and is in no imminent danger of such damage.

Look how shiny the ball is in Brian’s photo. There’s a J.J. Abrams lens flare coming off that thing. That’s the shellac. A true Rahrball, like the one in the collection of the Hall of Fame, pictured at the top of this story, won’t have that sheen.

Even if it wasn’t the genuine article, great find, Jeff!

Now that we know what to look for, let’s all keep our eyes peeled at museums, memorabilia events, antique shops, and in old, dusty attics. If you see a non-shiny yellow ball stamped with Ford Frick’s name, keep calm, discreetly take a few pictures, and send them to Project 3.18 for a careful and authoritative evaluation1.

Yeah, we’re just going to ask Brian. He has to answer all our emails now. Scholar Code.

Hot damn! Reading your stuff makes my day better!

As it turns out, I am headed to Cooperstown in a couple of weeks. I will try to remember to ask about the 1938 Rahr baseball.