That Kind of Game - Part 2 of 2

On a wild night in Boston in September 1974, an anti-hero played hero and Fenway fans played an impromptu game of darts.

This is the conclusion of a story from 1974. If you’re starting from the top, here’s a link to the first half:

The season was getting late, first place was at stake, the New York Yankees were in town, and Luis Tiant was on the mound for Boston. This was not the kind of game where old friends planned to catch up on how the families were or reminisce. The 33,000 people filing into Fenway Park had come to root, root, root.

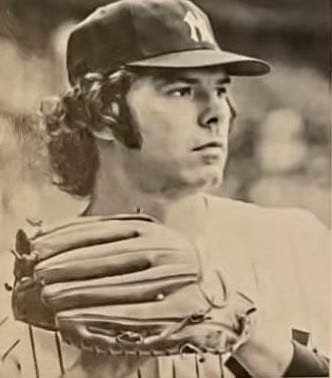

That night, one of the surprises from the Yankees’ strong pitching staff would face Tiant, one of the most surprising pitchers in baseball history. 32-year-old Pat Dobson1 had been one of the best pitchers in baseball across a two-month stretch in which he won six straight games. An earlier victim of bad luck, Dobson’s fortunes had turned when his teammates got hot, and while he sported a middling 15-14 record, his ERA was down to 2.96.

Dobson would have to be very good to match Luis Tiant, at the peak of his second act and nearly unhittable that night. The Red Sox pitcher was recovering from a case of the flu and not at his best, but he still took a no-hitter through eight innings.

Boston had failed to score in Tiant’s previous three starts, but in the first inning the Red Sox surprised him by scoring a lone, scratched-out run, helped by an errant throw from the Yankees’ sore-armed catcher, Thurman Munson.

Pat Dobson had gotten ready for the game by drinking seven cups of hot coffee, and after that first inning (in which he gave up just one hit), the caffeine kicked in. He gave up just a single hit in the second and then none in the third, the fourth, the fifth…

He was still cruising in the eighth inning, down 1-0 but as unhittable as Tiant. Watching from the dugout, reliever Sparky Lyle believed Dobson would triumph, somehow. “He’s pitched too good to lose this SOB.”

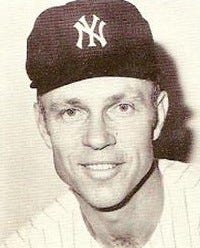

No less than the great Whitey Ford was the Yankees’ pitching coach in 1974, and Ford agreed. “That’s one of the best-pitched jobs I’ve ever seen up here.”

Maybe so, but Tiant was masterful, dumping his bag of tricky pitches over the Yankees’ heads. The night sped by. Everyone out on the field seemed to fade into a tableau vivant behind the pitchers staring each other down. For the game to end, one of them would have to blink.

In the top of the ninth, Tiant was still nursing that miniscule one-run lead, the only run his teammates had given him in his last 35 innings and counting. He got third baseman Graig Nettles to fly out, but left fielder Lou Piniella came to the plate and waged a relentless battle with the tiring pitcher, eventually drawing a walk. It was now or never for the Yankees, and manager Bill Virdon replaced the lumbering Piniella with Larry Murray, who was taking up a roster spot in anticipation of just this moment.

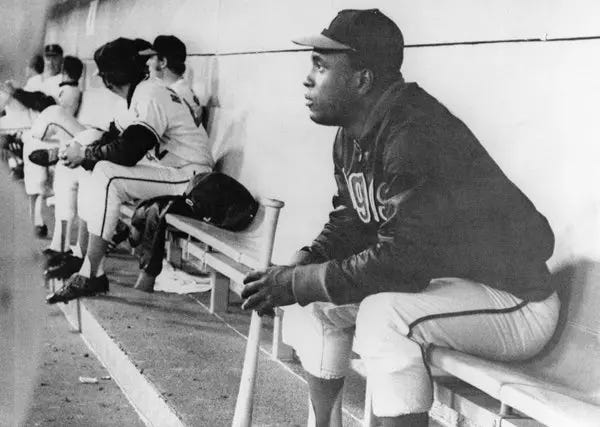

21 years old, Murray was a fringe outfield prospect who’d spent most of the year at Single-A Ft. Lauderdale, where he hit a paltry .207. That hit-tool would never play in the majors, but Murray could walk, and man, he could run. His 62 steals in 73 attempts beat the second-place finisher by more than 20 bags. The Yankees called him up in early September, hoping he could be a kind of “designated runner” during their playoff drive. Murray first appeared in a game on September 7, pinch-running and being caught trying to steal a base. He played two innings as a defensive replacement on September 8 without accomplishing anything and now on September 10 he’d have another chance to run.

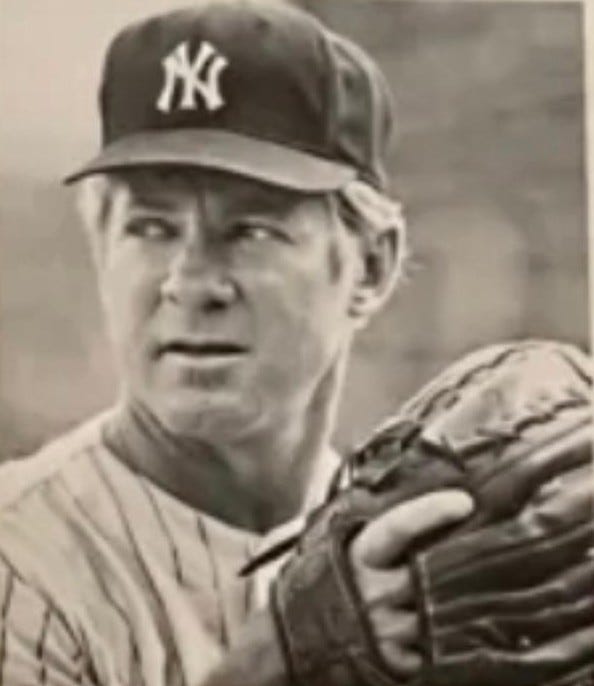

Chris Chambliss batted next. It had been a tough season for the first baseman, who was currently hitting .253, one of the lowest marks posted by any of the starters. He was 0-for-3 against Tiant up to that point, but Chambliss saw a pitch he recognized and lashed it into right field. At first base, Larry Murray took off.

Chambliss’ scorching hit bounced just once, with enough force to clear the low wall in deep right field. An eager spectator tried to grab it, but the ball escaped his nervous hands and dropped back down onto the field of play.

Right fielder Dwight Evans picked up the ball as Murray flew around the bases. The throw came in too late to catch Murray at home, but Evans was charging in hard right behind it, looking for an umpire as he shouted and gestured back toward the outfield wall.

Chambliss stopped at third base. It looked like a game-tying RBI-triple, but the score on the Fenway scoreboard hadn’t changed.

Evans found first base umpire Hank Morganweck, still pointing back toward the wall and the fan who’d touched Chambliss’ ball. Evans’ claim was that the ball had gone all the way into the stands when the fan touched it. It should have been a ground rule double, putting Chambliss at second and Murray at third.

“No question,” Evans said. “Hell, I was right there. It went over the wall and the guy dropped it back in play.”

Morganweck said he didn’t see that, claiming Evans’ pursuit of the ball had blocked his vision. He appealed to second base umpire Marty Springstead. Springstead seemed to agree with Evans, ordering Chambliss back to second base. Thus began 25 minutes of arguing.

The majority of the Yankees’ coaching staff got involved; first Virdon, the manager, Dick Howser, the bench coach, and even Whitey Ford who came running all the way from the outfield bullpen to make a personal appeal to the crew chief, Don Denkinger. Evans was playing them, Ford warned: “A fan reached for it, but didn’t touch it. Evans just used good judgment in hollering at the ump.”

The crux of the dispute was precisely where the fans hands where when they touched the ball. If they were in front of the wall, that fan had interfered with the ball in play. In cases of fan interference, the umpires were to use their judgement to place the baserunners based on where they likely would have been had no one interfered.

If that seems a bit technical, imagine trying to explain it to 33,000 frenzied fans whose team may or may not be in first place as a result of the decision.

The Yankees were arguing man-to-man, sending a player or coach to make their case to each of the four umpires on the crew. The officials retreated behind the pitcher’s mound, huddling in a knot and comparing notes. The Fenway scoreboard operator waited, leaving the spot where the Yankees’ run would display pointedly blank.

Denkinger asked Morganweck if the fan touched the ball before or after it went into the stands.

“I don’t know,” Morganweck answered. “I didn’t see it.”

“You didn’t see anything?” Denkinger asked.

“Didn’t see it,” Morganwreck said.

The crowd was growing impatient. Fights began breaking out in the stands as people’s emotions and beverages overcame them. The Yankees’ dugout was pelted with trash and debris. Virdon complained to the umpires, and the public address announcer warned the crowd of a possible forfeit.

“In the bullpen, Rick Dempsey was hit by a bottle,” Ford said. “It’s not bad enough that we had trouble winning up here, but then we have to put up with this.”

Through all of this Chambliss had kept his position at third, not giving it up until someone ordered him to do so—and thus far no one had. Suddenly he felt a sharp sting. “I look down and there’s a steel dart embedded in my arm, right through the shirt.” He had become someone’s triple-20.

Looking around, Chambliss realized this game had evidently been going on for some time. “There must have been 10 darts thrown out there,” he said. “I guess I was lucky just to get it in the arm.”

Chambliss plucked the dart out and the team’s trainer applied a band-aid. It was reported that third-base umpire Russ Goetz “ejected the dart,” and we really wish we could give you more details on how he did so.

Whitey Ford had seen enough. He walked back out to the bullpen, giving the left field line a wide berth. “I saw darts all over the infield,” he said. “I decided I’m going back to the bullpen where they only throw bottles.”

Meanwhile, the umpires had come to a decision, and the first thing they did was motion Chambliss back to second base. The crowd roared with joy and looked for Murray to emerge from the dugout and head to third. But that did not happen, and soon the scoreboard operator reluctantly did their duty—Murray’s “1” was put on the board, tying the game.

In those days there was no practicable way to offer the whole crowd a detailed explanation, but Marty Springstead gave one later.

“The call was this,” Springstead told reporters:

I thought the fan reached over the fence to touch it, thus it was spectator interference, which is different than a ground rule double, which lands in the stands. Spectator interference allows the umpire to decide where the runners would have ended up had the interference not occurred.

By ruling the fan had interfered, the umpires could decide how far Larry Murray would have gotten, and they all agreed that dude could fly.

Once he understood what was happening, the Red Sox’ manager, Darrell Johnson, took his turn with the umpires, but they were all getting pretty worn out from the screaming and the darts. Johnson soon became the game’s lone2 ejection.

Virdon, playing for the win, removed Chambliss from the game for another pinch runner. Luis Tiant remained on the mound and intentionally walked Thurman Munson.

With a runner in scoring position and a tie game, Virdon kept pushing. The next batter was a reserve infielder inserted during a previous double-switch, so Virdon went back into his bench, which was rapidly emptying out. He’d already used his first-choice pinch-hitter, Ron Blomberg, so the manager went to the best bat left.

Alex Johnson took his first at-bat as a Yankee in the bottom of the ninth inning of a tie game at Fenway Park with two runners on base and first-place hanging in the balance. How can you not be romantic about baseball?

Luis Tiant struck him out. How can you not be romantic about baseball?

Tiant then got the Yankees’ two-out batter, Sandy Alomar, to pop out and end the threat, but his 21st win was going to have to wait for another day.

“The umpires are gutless,” Tiant said. “They ought to be fined. But I’m arm-weary now; I’m forcing every pitch. I can’t go more than nine again. I’m dead tired.” In his last four appearances Tiant had allowed zero earned runs and had zero victories to show for it. Stats like these have given generations of Red Sox fans a complex.

The Boston Globe would later report that a “Boston cameraman” had recorded tape of Chambliss’ hit bouncing into the stands. According to that secondhand footage, the ball bounced once behind the wall before the fan grabbed at it and knocked it back onto the field. Ergo, the umps had blown an admittedly tough call.

None of this could ever happen today, could it? There are twelve cameras for every umpire and a control center at MLB headquarters in New York that looks like something straight out of a NORAD facility. The umpires would review it themselves, or a manager would challenge, and everybody would wait patiently for the giant videoboard to show them precisely what happened.

Is baseball better for all this silicon-powered accuracy? Yes, absolutely. Is it more interesting? No, definitely not.

Dobson returned to the mound for the bottom of the ninth. The Red Sox managed to load the bases, but Virdon held his peace and Dobson escaped by striking out Rico Petrocelli. At the end of regulation the score was tied, 1-1.

Diego Segui replaced Luis Tiant for Boston. Segui was Boston’s most used back-end reliever, there being “not much else to choose from” in the Sox’ bullpen, which had a curious hole the approximate size and shape of the Yankees’ Sparky Lyle.

Segui retired the side in order and Pat Dobson came out for his tenth inning of work and did the same. Dobson’s continuing role in this affair is the second thing that would never happen today.

“It was the longest, biggest, and best game I’ve pitched in the big leagues,” Dobson said. Pitching in the 1970s: if it ain’t broke, what’s to fix?

In the 11th Dobson gave up the biggest of his four hits allowed. Dwight Evans hit a booming two-out double to left field that fell ten feet short of ending the game. Carl Yastrzemski was intentionally walked, and Dobson faced Cecil Cooper. Cooper hit a sharp ground ball that looked like something, but second baseman Sandy Alomar laid out on the outfield grass to bring it down and made an off-balance throw to Bill Sudakis at first. Sudakis, the self-proclaimed “renegade,” stretched so far to make the catch that he pulled his hamstring and had to be helped off the field.

Pat Dobson had thrown eleven innings, giving up just four hits and no earned runs—with just three strikeouts.

“10 was my tops before this,” Dobson said. “Bill told me I was through after 11…he said he needed me in three days and 11 innings were enough.”

In the top of the 12th, Diego Segui returned for his third inning of work. The Yankees had used 17 position players thus far, including three different first basemen and shortstops. With so many players already subbed out, anyone entering the game was in for the duration, however long that was. Alex Johnson had remained in the game as the left fielder, so he got another at-bat.

Johnson saw an outside fastball he liked and swung hard, making good contact. The ball rose over center field and kept going, coming down in the bullpen. His fifth home run of the year smothered the fiery crowd like a pile of wet sand.

Johnson rounded the bases, showing no emotion. “I don’t get too excited,” he said. “I’ve been in baseball 10 years now, and this may be the only hit I get the rest of the year.”

When he returned to the dugout, he returned to his spot at the end of the bench without so much as a handshake. “He says he doesn’t shake hands after striking out, so why do it after a home run,” a teammate explained.

“That’s Alex Johnson,” pitcher Rudy May said. He had played with Johnson on the California Angels. “He’ll sit all alone on the bus to the airport. But if he’s left alone he can and will play this game near as well as it can be played.”

Dobson asked to go back out for the 12th. “I wanted to go back after them.” Virdon wouldn’t hear of it. To inflict maximum pain on the Red Sox in this situation, only one pitcher would do.

Sparky Lyle walked on with his usual swagger. There was no entrance music for him at Fenway, and in fact the pitcher had asked the Yankees to cut that stuff out back in April, but everyone present could hear “Pomp and Circumstance” in their hearts as baseball’s first modern closer3 arrived.

Lyle struck out Petrocelli. He struck out pinch-hitter Deron Johnson. Boston’s last chance was a 24-year-old rookie outfielder down at the end of their own bench, called up just a few weeks earlier. Lyle got Jim Rice to ground out to complete his 20th consecutive scoreless inning and earn his 14th save. See you next time, kid. If there is one.

The New York Yankees were alone in first place.

Alex Johnson had created his own worst nightmare—a postgame crush of eager reporters wanting to hear all about his feelings.

He showered and dressed in record time, fending off the press and betraying no hint of happiness or even satisfaction. He wasn’t about to be a part of anyone else’s fun moment.

“Sometimes you’ve got to be lucky,” he said of his home run. “I’ve been playing this game for 10 years. It’s the same old story. I like to hit, and it’s no different here than anywhere else. I’m no hero. Give credit to the defense and the pitching.”

He fled the clubhouse, which was particularly odd as the entire team was due to board a bus together within the half-hour. He emerged from whatever closet he’d been sheltering in in time to get on the bus and find his empty row.

Dobson, on the other hand, was happy to take the credit for what Peter Gammons hailed as “one of the best-pitched games in Fenway Park’s history.” The pitcher had switched from coffee to orange juice and vodka. “I guess I would have to rate it one of my best games, especially since it was so important to all of us.”

Chris Chambliss was unavailable after the game. He had been whisked away to receive a tetanus shot before the team departed for Baltimore. Such was the life of a baseball player in the 1970s.

It had taken almost two full lineups of players to do it, but the Yankees had slain their monster. After what one writer called “their biggest victory in 10 years,” the team left Fenway with a clear path toward their future.

With so many deserving performances in one night, there was glory aplenty to spread around. Alomar, Sudakis, Chambliss, Lyle, Dobson, Johnson, and Larry Murray, the rookie speedster, whose game-tying run in the ninth was his only meaningful contribution to the team that season.

“Hell,” sportswriter Phil Pepe wrote, “give them all a hand. It was that kind of game.”

The 1927 Yankees they weren’t. The 1977 Yankees they weren’t. But—if you squinted—the Yankees they almost were.

While it isn’t listed on his Baseball Reference page, one account from that evening reports Dobson’s nickname was “the Snake.” That’s not going to come up again, but we wanted you to know.

Darrell Johnson’s ejection checks the necessary box for a Chaos Game, but was fairly routine as tantrums go. We wish he had taken third base with him or at least turned his hat backwards.

As the term “closer” didn’t exist in 1972, Lyle’s first Yankee manager called him the bullpen’s “lock-up man.”

This “chaos” game was a little (or a lot) of everything! Pitching 12 innings (many pitchers now barely make it to 5), darts thrown at players, Chambliss’s tetanus shot. This must’ve been fun to write!

“Lock-up man” as in for the manager, his job is done, get these guys out and lock up when you’re finished.