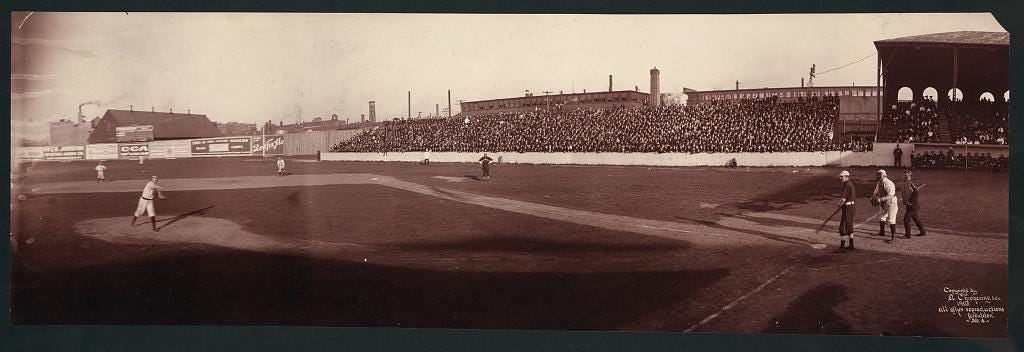

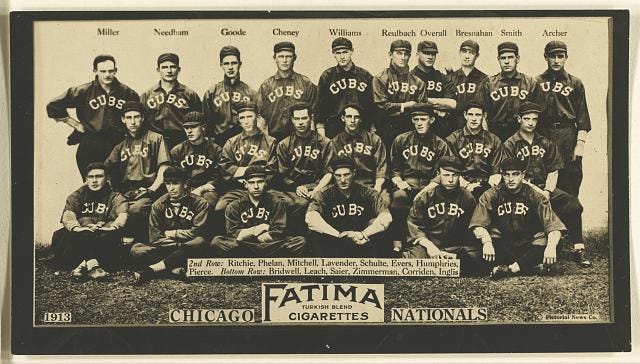

When the Game Was Sepia

In our WGWS features, we’ll tell stories from exploring baseball’s early days through the mid-twentieth century. We often associate this era with the sepia-toned or black and white photographs that serve as our remaining visual link to the players, the ballparks, and the people in the stands, or standing on the field itself, wearing their Sunday best (and occasionally throwing their seat cushions). These are baseball’s origin stories, with heroes, villains, top-notch names and terminology, unfamiliar rules and customs, all contributing to the burgeoning cultural institution that muscled its way into American life apace with America’s emergence as a global power. The joy of telling stories from so long ago is in sharing both the unrecognizable and the eerily-familiar. In When the Game Was Sepia, we’ll explore how early fans both laid the foundations for modern-day rituals and ruined some things for the generations that followed.