Arms and Armor - Conclusion

Safety caps decided the 1941 National League pennant, but squabbling inventors (and a world war) kept universal head protection off the market.

This is the final installment in our series on the first major attempt to get major league batters to wear head protection. Here’s the story so far:

In Part 1, a series of notorious 1940 beanings pushed the National League toward action, resulting in an unsightly protective liner.

In Part 2, a far superior “armored cap” was invented by a motley crew of experts, organized by Brooklyn’s president, Larry MacPhail, who made it mandatory for all players in the Dodgers’ system.

In Part 3, history’s unluckiest Dodger, Pete Reiser, proved the new head gear was as safe as it was unassuming.

In Part 4, the safety cap’s creators squabbled and teams learned the hard way, placing their orders only after high-profile players were beaned.

In today’s conclusion, a New Jersey Viking (you read that correctly) tests the Dodgers’ caps like never before, while competing wellness initiatives help decide a National League pennant race and the future of protective headwear.

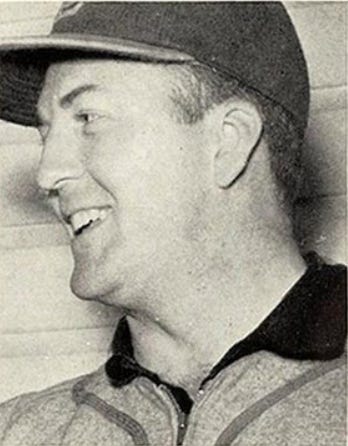

In 1941, Gordon Stanley Cochrane was a “manufacturer’s agent,” selling rubber, wire, and steel to Detroit automakers. It was a living, and by his account a pretty good one.

Four years earlier this mild-mannered salesman had been Detroit’s foremost Tiger, player-manager Mickey Cochrane, the toast of the upper Midwest, widely regarded, then and now, as one of the best catchers ever. That life vanished in an instant in 1937, when a Yankees pitcher named Bump Hadley lost control of an inside fastball.

“I saw it halfway to the plate,” the retired catcher said of the pitch that fractured his skull and ended his playing career, “but afterward I lost sight of it and the next thing I know I was in the hospital for two months. I don’t say Hadley threw a deliberate bean ball at me. But I do say he all but put me out of business. I never caught another game.”

In February 1941, Cochrane assured a reporter he was “done with baseball,” but he didn’t sound entirely certain. The National League’s recent introduction of head protectors might have given him a spark of hope. With adequate protection, perhaps it might be safe for him to venture back out onto the field. “Were I to return to the diamond,” he said, “it would only be on the condition that I could wear a helmet whenever I went to bat.”

“Black Mike” Cochrane had been one of the toughest and most aggressive players in the game, and from his forced retirement he scorned other players who feared ridicule more than a four-seam career-ender. “Let ‘em yell,” he said. “There’s no fun in being conked by a fastball. The helmet for batters is bound to come. I only wish it had made its appearance in my time.”

After trading the National League lead back and forth for three months of the 1941 season, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals spent a good chunk of August deadlocked at the top. The teams were so evenly matched that little things—like pieces of plastic—would prove enough to decide the winner.

On August 10, the Dodgers played a doubleheader in Brooklyn against the Boston Braves. Managed by Casey Stengel, the Braves were well out of the race, stuck in seventh place in an eight-team league. Even from this lowly station, Boston pitchers would manage to leave a mark on the pennant race. Several marks, in fact.

In the first game the Dodgers scored three runs off the unfortunately named Manny Salvo and Stengel quickly pulled him in favor of a 29-year-old righthander named Dick Errickson.1

Brooklyn torched Errickson, scoring 10 runs on 10 hits. Outfielder Joe Medwick was in the center of the action with two singles and a home run. He had struggled in the year since his 1940 beaning, but Medwick had lately been resembling the “Ducky of old” at the plate, and pitchers were taking notice. In the National League of this era there was nothing more hazardous to batters than their own success.

When Medwick came to bat in the fifth inning, his team up 7-2, he surely had some idea of what was coming, and it did. With the first pitch Dick Errickson “dusted Medwick off,” sending him diving away from an inside fastball. This was practically a compliment under the circumstances, and the hitter did not complain. But Errickson surprised him by coming right back inside, and this time Medwick couldn’t spin away fast enough. The ball cracked off his elbow.

Wincing in pain, Medwick could not continue. Next up was Dolph Camilli, Brooklyn’s chief run producer, having an outstanding season. Dick Errickson threw one pitch and hit Camilli on the head. The ball bounced harmlessly off his safety cap.

Camilli later described it as ”a new sensation, like bumping your head against the wall, only without any pain.” He blinked and jogged to first, grinning at his good fortune. Errickson’s various “purpose pitches” had loaded the bases, and Brooklyn’s Dixie Walker took advantage, hitting a two-run double that made it 8-2.

In the sixth inning, with one out and runners on second and third, Errickson faced Pete Reiser.

After avoiding a serious beaning injury back in April, Reiser spent 1941 doing a pretty good imitation of Ty Cobb. Batting third, he hit .343, including 39 doubles, and scored 117 runs while playing a flashy center field. And while his teammate, Dolph Camilli, beat Reiser out for the MVP award, modern statistics suggest the writers at the time got that wrong. A full third of Pete Reiser’s career value by WAR came from just his sterling 1941 season.

If there was a red flag, it was the fact that Reiser had been hit by seven pitches already. Dick Errickson made it eight, beaning the Dodger for the second time that year. The ball caught his shoulder and ricocheted off the side of his head, but this time the safety cap caught the full force of the blow.

Reiser was unharmed but his teammates were understandably furious. Mickey Owen, on the field after recovering from his own beaning a month before, noticed one of the Boston coaches, George Kelly, laughing. He started for Kelly “with mayhem on his mind,” with Dolph Camilli right behind him. An umpire and manager Leo Durocher got between the two men before any mayhem was committed, but “the clans gathered” in front of the Brooklyn bench for a brief airing of grievances. When order was restored, Medwick’s replacement, Jimmy Wasdell, singled in two more runs.

The Dodgers won the game, 14-4, and they won an entirely different sort of game, 1-0, that afternoon. Elsewhere the Cardinals won both ends of their own doubleheader, keeping the two teams knotted atop the standings. But only the Dodgers had faced Boston pitching and emerged relatively unscathed. “The Dodgers’ pennant hopes were saved by the once-scorned helmet,” the New York Daily News declared. Even Medwick was not seriously hurt. He returned the next day, the angry welt on his arm stained brown by iodine, and hit another home run.

Afterward, Dick Errickson recouped some dignity by visiting the Brooklyn clubhouse “to count the wounded” and presumably apologize. He said he’d thrown at Medwick on purpose just the first time; the subsequent beanings were accidental.

Leo Durocher said he was inclined to believe Errickson, particularly with the pitch that hit Reiser. “By that time he was so rattled he didn’t know whether he was pitching to center field or the plate.”

The Dodgers weren’t the only club running a wellness initiative in 1941. Just a few weeks before Larry MacPhail issued General Helmet Order #1, his counterpart in St. Louis, Sam Breadon, announced the Cardinals were going all-in on…vitamins.

The Cardinals’ president had procured 5,000 capsules of vitamin B1, otherwise known as thiamine, described at the time as “an anti-neurotic which has been effective in relieving nervousness, indigestion, and lack of energy.” Asked during spring training if the players would be required to take the supplements, Breadon said, “Well, of course we can’t force the players to swallow the capsules, but the club would like to see the men in line regularly” to take their pills. We are imagining a baseball version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

On August 20, the B1-fortified Cardinals held a scant 1.5 game lead over the Dodgers. In between series with the Pennsylvania teams, the Cardinals were in Boston for a doubleheader against Stengel and his free-slinging Braves. At this point in the season the Cardinals organization had followed the crowd and procured 16 safety caps for their players, but unlike the vitamins, these weren’t mandatory, and no Cardinal had used them. Perhaps you can guess where this story is going.

In 1941 the heart of the Cardinal club was its longest-tenured member, center fielder Terry Moore. Moore was an exemplar on the field and an enforcer in the clubhouse, making sure his teammates, who respected and feared him, observed the tenets of the Cardinal Way at all times. He was coming off his best season as a player in 1940, and at the beginning of 1941 he’d been named team captain. “The Cardinal team is built around speed, hustle, and Terry Moore,” The Sporting News proclaimed. If he’d put on a safety cap, the rest of the players would have followed.

In the third inning of the first game against the Braves, Boston’s pitcher, Art Johnson, lost control of a fastball and Terry Moore appeared to “freeze,” which is what people called it when a player was hit before he began trying to get out of the way. The pitch struck Moore in the left temple and he crumpled.

Players crowded in. A dozen physicians emerged from the grandstand to help administer first aid. Priests waited in the on-deck circle. Moore lay unconscious for an excruciating 10 minutes. “It reminded everyone present of Mickey Cochrane’s beaning,” one writer said. The center fielder woke up in the clubhouse.

Some skeptics insisted that a safety cap would not have covered the spot where Terry Moore was struck. Perhaps that was true, but St. Louis’ players seemed to make their own statement on the matter the next day in Philadelphia. “Most of the Cardinals will be wearing safety caps today,” a writer said on August 21. “They should have been wearing them yesterday.”

Meanwhile, “St. Louis’ pennant hopes rested in the X-ray room at Boston’s St. Elizabeth Hospital.” Terry Moore’s exam showed no fractures. He was diagnosed with a “simple” cerebral concussion and a lacerated scalp, but there is no such thing as a “simple” concussion. When the brain bounces off the inside of the skull, things tend to get complicated.

So it was with Terry Moore. On August 26 reports said “the odds are against Moore playing again this season.” Moore pushed himself hard, probably too hard, to get back and help the team. He managed to return, on September 14, but he was suffering from periodic dizziness and was not the same hitter. In his final 12 games Moore’s batting average dropped from .303 to .294.

It was too late. During the month that Moore was out of action, the Cardinals and Dodgers played six head-to-head games. The Dodgers, boosted by Pete Reiser, Dolph Camilli, and Joe Medwick, won four of those crucial contests. When the 1941 season ended Brooklyn won the pennant over St. Louis by a margin of 2.5 games.

It is hardly a stretch to say that the Brooklyn safety caps helped deliver Brooklyn its first pennant in a generation. Dr. Walter Dandy certainly thought so. Speaking at a New York State Medical Society meeting in late September, the neurosurgeon who helped designed the safety cap said he did not have “formal” outcomes to report, but as a baseball fan he thought that Brooklyn’s pennant flag amounted to quite the peer-reviewed study.

Safety caps had saved teammates Dolph Camilli, the MVP, and Pete Reiser, the actual MVP, who together went on to lead their team to the World Series. It seemed like the perfect start to a revolution, but after 1941 no revolution came.

Players still wore safety caps in 1942—and in every other season until something better came along—but the dominoes stopped falling as they had the year before. No new teams began requiring head protection and among the teams who had already embraced it, supply and usage of the armored caps began to dwindle.

Why did the movement stall? We see a few possible reasons.

Supply chain issues had constrained the cap’s production from the outset; even the Dodgers occasionally had trouble getting every player outfitted in the latest version. The cap’s production depended on specially manufactured parts made by DuPont, a petrochemical behemoth and major military contractor. After the United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941, companies like DuPont would have been required to dump every shred of plastic they could into the war effort.

The war, with its all-encompassing disruption to American life, might have stifled baseball’s appetite for institutional reform in addition to its supply of plastic. Many players left for wartime service, replaced by, well, replacements; not the kind of investments a team owner was going to lose sleep worrying about. If a fill-in player didn’t want to wear a helmet, that was his problem.

After 1942 the Brooklyn safety cap temporarily lost its greatest champion. In October 1942 Larry MacPhail left the Brooklyn Dodgers2 to rejoin the Army. MacPhail was made a Lieutenant Colonel and assigned to various public and media relations duties that kept him out of trouble for the duration of the war. When he left the service, MacPhail joined two businessmen to purchase the New York Yankees, and in this tripartite regime helmets seem to have been less of a priority.

MacPhail’s Yankees won the World Series in 1947, defeating the Brooklyn Dodgers, but in the aftermath the executive’s tempestuous personality blew him out of baseball at age 57. He retired, turned his attention to horseracing, and soon got thrown out of that, too. And so on. The pioneer of radio broadcasts, night baseball, and head protection died in 1975 at age 85.

In a characteristic act of self-sabotage, it may have been MacPhail’s efforts to secure control of the Brooklyn safety cap that snarled its market momentum. Products stuck in legal limbo are harder to distribute.

On June 18, 1941, with no relief coming from baseball’s leaders, Walter Dandy had forged ahead, submitting a patent application seeking sole ownership of the rights to what he called “a Protective Cap.”

According to Dandy’s biography, Larry MacPhail either disputed Dandy’s patent or submitted his own application for the same invention, essentially forcing the United States Patent Office to pick a winner. The legal wrangling and bureaucratic plodding took years, even after MacPhail had left the Dodgers and joined the Army, leaving the mess for his successor, Branch Rickey, to clean up. MacPhail seems to have hoped Dandy would simply fold. Patent attorneys were expensive, and Dandy was dumping money into what amounted to an effort to give something away. “There is nothing to it If I win,” he complained to his lawyer, but he stuck it out.

The final determination came in November 1943, when the Patent Office assigned the patent for the safety cap (formerly of Brooklyn) to the doctor from Baltimore. What Dandy did with it is unclear.

Safety caps remained the standard in head protection for the rest of the decade, but by the time Dandy got around to making a distribution plan with the Spalding sporting goods company it was already 1945. In 1946 he died of a heart attack at 60 years old. Despite holding the patent, of the three men involved in the invention of the safety cap, Walter Dandy has historically received the least credit.

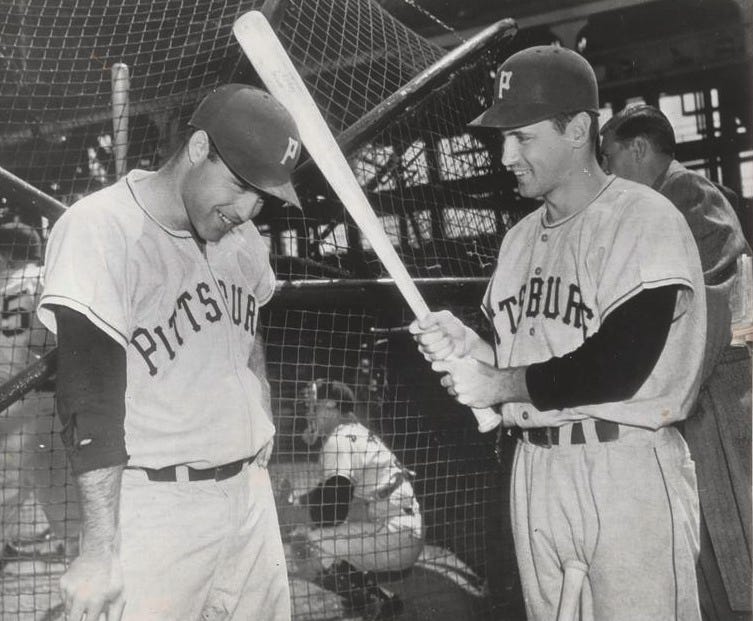

By the early 1950s baseball could have all the plastic it wanted, and in 1952 Branch Rickey, now the general manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates, picked up where MacPhail had left off. In order to avoid any messy patent disputes Rickey founded the American Baseball Cap company in 1952 and then announced that in 1953 all Pirates would wear ABC’s patented high-tech helmet.

“You could have put a light on the front and gone into a cave,” Pirates catcher Joe Garagiola said of the ABC helmet. You really could have. The new helmet, made from fiberglass and polyester resin with a leather-padded interior, was inspired by cutting-edge mining equipment.

Former Pirates’ manager Frankie Frisch called the helmet an “inverted trash can” and said the take-no-prisoners pitchers of his generation would have “played a tune” off of its hard shell. Fans at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field reportedly tested the Pirates’ helmets by throwing marbles at them.

Garagiola recalled the moment in 1952 when he and the other Pirates bought in. A helmeted runner, Paul Pettit, was on his way to second when the shortstop fired a wild throw that struck Pettit in the head. The ball had been thrown so hard it dented the helmet, but Pettit was fine. “Made believers out of everybody,” Garagiola said. By 1955 nearly every team was offering to outfit their players with helmets, and every year there were more takers.

In 1956 the National League required all new players to wear some kind of protective head gear. The American League followed in 1958. After the 1970 season, both leagues jointly moved to require helmets; a Dandy-type safety cap would no longer suffice. There was a carveout for players with big league experience prior to 1971, who could opt to continue wearing lesser protection.

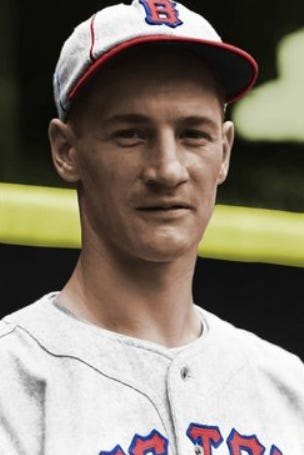

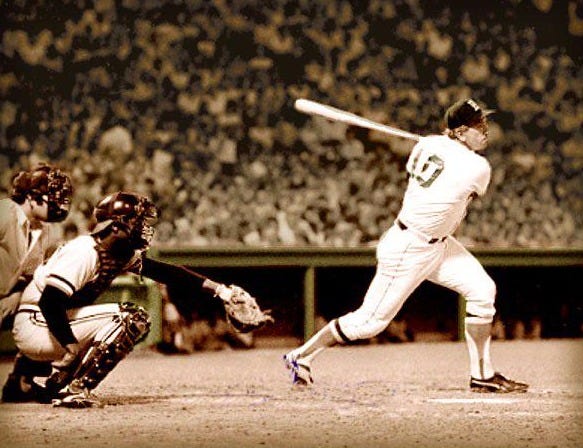

Three three players went this route. One of them was a second-string catcher named Bob Montgomery. A rookie with the Boston Red Sox in 1970, Montgomery’s 86 at-bats that September entitled him to go without a helmet for the rest of his 10-year career.

Four years after Larry MacPhail had died, the last domino fell on September 9, 1979. Wearing only a flimsy liner under his cap, Montgomery took the final helmetless swing in the majors and grounded into a ninth-inning double-play.

In 1285 career at-bats, he had never once been beaned.

We hope you enjoyed our serialized December tale. If you liked the format and wouldn’t mind seeing another one like this in the future, let us know. Leave a comment, leave a Like, or restack this post to let other readers know you just finished something they might enjoy, too. Thank you for any and all of these efforts that support this baseball history project!

That’s it for 2025 here on Project 3.18. We had a great year and are grateful to each and every one of you for being a part of it. Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, and all our best for 2026.

We’ll be back on January 5 to begin our much-anticipated eight-part series on the invention of the jockstrap.

…Kidding!

Dick Errickson had one of the best nicknames we’ve seen in a while: “Leif.”

Yes, it’s a bit obvious, but it actually worked on several levels. Leif Eriksson, the famous Viking explorer, discovered a part of Canada and named it “Vinland.” Leif Errickson, the pitcher, hailed from…Vineland, New Jersey.

When they lost MacPhail to the war effort, the Dodgers replaced him with his former mentor, Branch Rickey. Rickey was unquestionably “pro-helmet” but after the war (and the death of segregationist commissioner Kenesaw Landis) Rickey prioritized a cause he deemed more urgent—the racial integration of major league baseball.

Really enjoyed the series Paul thank you for the interesting education! I am an advocate (have written a post on protecting pitchers from line drives), of the idea pitchers in Little League should begin to wear more head protection than a baseball cap. That way the hurlers will be accustomed to it as they get older and better. With increasing exit velocities in MLB the unthinkable is not so unthinkable! Happy Holidays to you and your family!

A really cool & fascinating clip Paul. As usual I learned a lot from you.

I hope Ken Burns is reading your work - it would certainly be beneficial to him.

Enjoy the Holidays & the time off.

As football begins winding down baseball is around the corner peeking her head out.

I’m curious as to what is coming in March for baseball. I’ll have to Google it as I only saw it advertised but one time.